Why are Subject Tests required by drastically fewer colleges than a decade ago? Is the relevance and popularity of the tests actually diminishing? Are the tests likely to survive or will they be discontinued by the College Board?

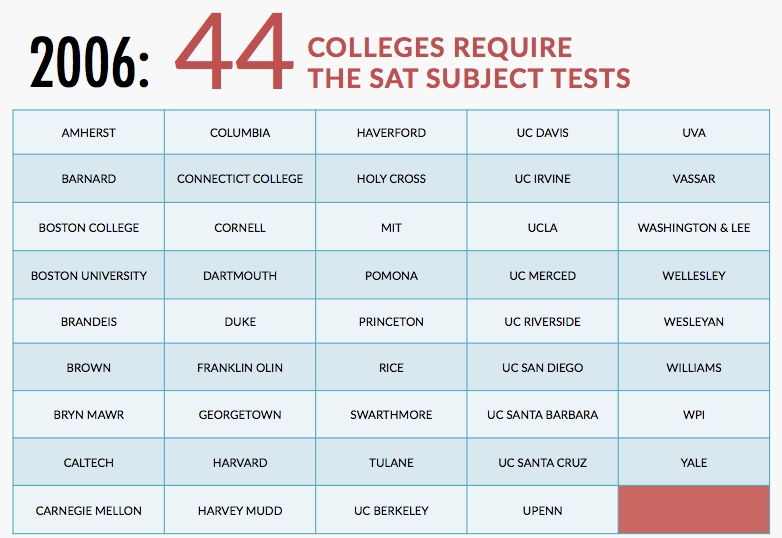

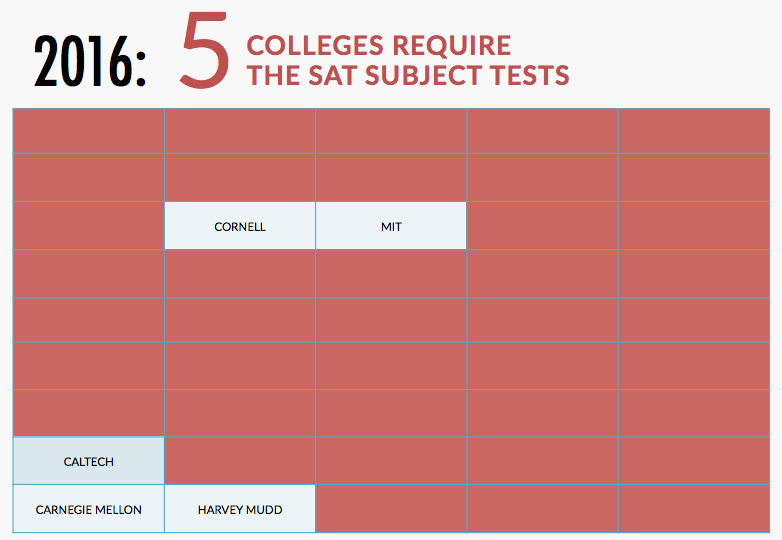

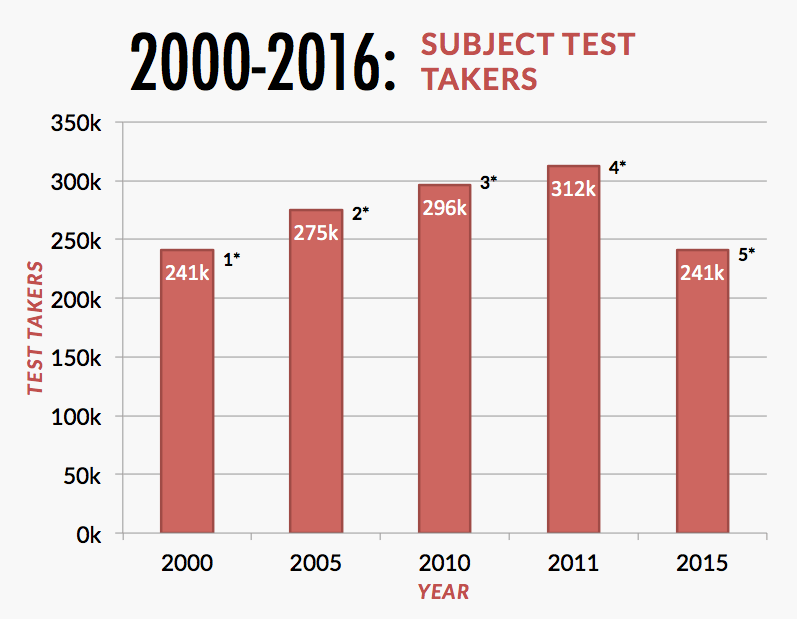

The perceived necessity of College Board’s Subject Tests has been on the decline since 2005 when the SAT II Writing test was essentially folded into the SAT. Subject Tests are explicitly required (no substitutions or exceptions) by only five U.S. colleges, about 90% fewer than just a decade ago.

Astute readers may note that the removal of the Subject Test requirement does not seem to correspond with a weakening of the competition for admission to these elite schools. In fact, the precipitous falloff in colleges requiring Subject Tests overlaps with increasingly lower admission acceptance rates and has resulted in only a modest decline in the numbers of students who choose to take Subject Tests anyway.

A likely explanation is that students are correctly divining the implied expectations of the more than 80 highly regarded colleges who may not express an official requirement but still recommend, consider, or substitute Subject Tests in their admission evaluations. We maintain a complete list here.

What is the future of these tests that are explicitly required by so few colleges and taken by less than 1/10 of the students who take the SAT or ACT? Are the Subject Tests dead weight that will eventually be jettisoned, or will they stubbornly hang on?

College Board CEO Waffles on Fate of Subject Tests

At the National Association of College Admission Counselors (NACAC) annual conference in Columbus, OH in September, College Board CEO David Coleman was asked a trap question by a test prep insider: If a guessing penalty for wrong answers is bad (as Coleman had just stated), then why haven’t the Subject Tests been reengineered to follow the new SAT’s lead and drop the guessing penalty?

I was in the audience listening carefully and expecting a dodge, but instead we heard the first public acknowledgment that the cost of redesigning Subject Tests might not make sense, because the tests may not be around forever. Coleman’s statement was officially disavowed a few weeks later by a member of his staff in a post to the NACAC listserv: Subject Tests are not going away and more and more students are taking Subject Tests (this claim of an increase is actually refuted by the College Board’s own data, as depicted in the chart below).

However, in a walk-back of the walk-back, at the College Board Forum in Chicago in October, Coleman was again asked this question and again admitted that the fate of the Subject Tests program is unclear and will be determined by the “market.” The College Board is considering multiple avenues, one of which includes updating all of the tests to align with the new SAT scoring methodology. Also on the table is the possibility of updating only the most popular subjects and letting go of subjects like World History and some of the language tests. Coleman was intentionally vague about when College Board would announce its plans. Audience members were left to wonder whether the organization’s leader is simply drifting off-message in his public remarks or whether we should take at face value his intimation that Subject Tests may not survive. The latter seems like the safer bet.

Ironically, this question of whether Subject Tests, née SAT II’s, née Achievement Tests, will be saved, executed, or allowed to die slowly is playing out against a backdrop in which College Board has fallen in love with achievement, rather than aptitude, as the 21st century raison d’etre for its exams. In a Common Core world, when tests reflecting student achievement are held up as the gold standard, why is there so little affection for the tests that used to have “Achievement” in their name?

Below we try to unpack what this all means for students and what the future might hold. (A hat-tip to my colleague and co-author Art Sawyer for his analysis and color commentary.)

Popularity of Subject Tests Over Time

Subject Tests have been given so many stays of execution for a number of reasons, and the best measure of whether Subject Tests still matter is in the number of students still taking them. Students are making perfectly rational decisions about Subject Tests — although sometimes in response to irrational college policies. Students must make decisions that keep options open and serve as insurance. For many, Subject Tests are a precautionary purchase. You may not need insurance, but if you do, you really want it in place. Subject Test test-taker behavior is certainly more rational than the 60% of SAT and ACT takers who spend money on the SAT and ACT essays relative to the 10% of colleges that still require those essays. This reveals that parents and students are conservative when it comes to evolving advice. It took decades of assurances that “the SAT and ACT are treated equally” for the SAT and ACT to achieve near parity in the marketplace. Even now, though, the most competitive colleges still receive more SAT scores than ACT scores.

Here are the trends in numbers of test-takers and numbers of tests taken since 2000. Footnotes: 1* The class of 2005 was the last to take the old SAT II Writing test. For the class of 2006, this test was essentially incorporated into the SAT as part of the overhaul that resulted in the SAT being three separate scores totaling 2400. 2* Even though the SAT II Writing was folded into the SAT in 2005, the number of Subject Test takers continued to increase – for a variety of reasons but in part because now students had to experiment to find the next best alternative. 3* The class of 2011 was the last class required to take Subject Tests to be considered for admission at the University of California campuses.

Footnotes: 1* The class of 2005 was the last to take the old SAT II Writing test. For the class of 2006, this test was essentially incorporated into the SAT as part of the overhaul that resulted in the SAT being three separate scores totaling 2400. 2* Even though the SAT II Writing was folded into the SAT in 2005, the number of Subject Test takers continued to increase – for a variety of reasons but in part because now students had to experiment to find the next best alternative. 3* The class of 2011 was the last class required to take Subject Tests to be considered for admission at the University of California campuses.

As highlighted earlier in this post, many other colleges have joined the UCs in backing away from explicitly requiring Subject Tests of their applicants. These colleges tend to be selective, needing tools to help evaluate students’ abilities relative to one another and students’ readiness for challenging college coursework. And, like the UCs, these colleges are concerned about diversity and equity issues. Subject Tests can be barriers for students who are under-represented minorities or low-income and who lack access to the educational opportunities and counseling support that are reflected in Subject Test scores.

All of the above means that College Board is in an awkward position and faces a difficult decision. Redesigning and continuing to offer tests with limited popularity is an expensive proposition. Killing off Subject Tests would be a politically precarious move at a critical juncture. Having Subject Tests simply die off might be even more embarrassing.

Culling or Killing

The way College Board has allowed the language tests to wither is a good example of prestige over profits. The language tests are deadweight; they number more than half (12) of the subjects College Board must maintain but account for less than 10% of tests taken. 330 students took Modern Hebrew last year, 438 German w/ Listening, 492 Italian. Most of the students taking the language tests are simply demonstrating basic proficiency in their first language (97.5% of Korean with Listening testers were native speakers and averaged a 771); many colleges do not find this feat especially distinguishing. Chinese and Japanese language tests were added explicitly at the bidding of the UCs, and Korean soon followed. Even after the patron (UC) bowed out of the program entirely, though, it has proved dicey politically for College Board to drop the unpopular language tests.

The language exams are the SAT Essay of the Subject Test world. The support for the tests is such an afterthought that the language exams with a listening component still require a portable CD player! The class of 2019 has never lived in a world without an iPod. College Board might as well require a slide rule for Math 2.

Rational Decisions

For many students, taking Subject Tests is a safe decision in an uncertain world. You don’t want to miss the windows to take Subject Tests only to realize in summer before 12th grade that there are colleges on your list at which the tests are required or expected. Did you have Honors Bio in sophomore year? Might as well take the Biology Subject Test. You never know. When the UCs required Subject Tests, it meant not just dictating the behavior of all applicants, it meant dictating the behavior of all potential applicants. The aspirational schools still do the same thing. If you want to be technical about it, none of the HYPS require Subject Tests. Their level of “requirement” is one of degrees, but the gist is still “submit these unless you have a really good reason not to submit them.” 35,000 students apply to Harvard each year, but a significant multiple of that number consider applying at some point in their high school career.

Maximizing Options

Subject Tests are among the closest thing to a “freebie” as students can have. Withholding Subject Tests from view by exercising Score Choice is always in play, whether by explicit policy or through juror nullification. Taking a Subject Test should never decrease my options other than by squeezing out an SAT date (which, admittedly, is not inconsequential). Submitting Subject Tests might decrease my options. Being required to submit tests might decrease my options. But taking Subject Tests is about increased options and precaution.

The Power Tests

The crown jewels are Math 2, Biology E/M, Chemistry, and Physics. Those tests represent not just the most dependable tests; they represent the most important. Take them away, and you’ll have some painful meetings with engineering deans. A quote from a recent NACAC report titled Use of Predictive Validity Studies to Inform Admission Practices: “For engineers [at College J], factoring in the math II subject test [sic] relegated all three SAT sections to negligible impact.” Colleges love STEM. Almost 70% of Subject Tests taken are the math and science exams. Students want to prove their bona fides for science, pre-med, engineering, and dual-degree programs. Plain old SATs and ACT’s cannot reveal expertise in these subjects.

Equity issues, as much as predictive utility, have always been a driver of Subject Test policy. For a while, the tests drove decisions in favor of increasing equity. Multilingual students would have something to offset any weaknesses in English. That didn’t last long. It became clear that the better equity play might be to remove subject tests from the equation.

Consider Subject Test policy decisions as controlled by forces similar to those driving Test Optional policies. One of the worst things you can do as an admission office is turn away strong candidates before they even apply. Require Subject Tests, and you’ve put up a barrier that blocks some students. Don’t require Subject Tests, and you’ve taken away an effective sorting tool (at some colleges and for some programs). The best of both worlds is to use “signaling” to retain Subject Tests for many students while removing them as an absolute barrier. The key is to use language that the bulk of students will decide requires Subject Tests while allowing the language to signal to others that they can apply without Subject Tests.

Examples of signaling are readily available:

Dartmouth does not require Subject Tests: “We recognize that taking subject tests may represent a financial hardship for some students. If this is the case for you, we will consider your application without subject test scores.”

Yale does not require Subject Tests: “You may wish to consider whether there are particular areas of academic strength you would like to demonstrate to the Admissions Committee. Subject Tests can be one way to convey that strength.”

Princeton does not require Subject Tests: “Some students may find the cost of taking and submitting SAT Subject Tests to be prohibitive. Please note you will not be penalized for not submitting SAT Subject Tests if the cost of taking the tests causes financial hardship.” (Either that’s very poorly written, or it signals that you can be penalized for not taking Subject Tests when no financial hardship is involved.)

Stanford does not require Subject Tests: “Applicants who do not take SAT Subject Tests will not be at a disadvantage.” Stanford’s wording should be Exhibit A of signaling and double-speak. If there is no disadvantage, then why does your official policy state that Subject Tests are highly recommended? If you consider something supportively for those who do submit, then you are putting students who do not submit at a disadvantage. Which is it?

The Bottom Line is the Bottom Line

How many colleges say, “We require that you occupy a leadership position in an extracurricular activity?” Few even say that a leadership position is recommended. The attention accorded Subject Tests in policies at elite schools signals that students should try to differentiate themselves with that means. (Of course there are also specialized situations where students are in particular need of Subject Tests, such as for those applying to dual-degree programs or competitive STEM programs and for homeschooled and international students.)

The bottom line, though, is the College Board’s bottom line. It is increasingly difficult to justify the R&D and administration effort for Subject Tests. This is why we’ve seen the material grow stale, with tests repeated perennially and no attempts made to reinvigorate them.

As usual, students will wade into these choppy waters and try to make it to the other side despite the conflicting navigational information. Colleges and the College Board (their member-governed organization) have been unable to introduce more flexibility and choice and opportunity into admissions without dragging in more complexity and confusion. Our goal at Compass is to help you cut through the confusion and make the tactically correct decision in your particular situation. Feel free to contact us to evaluate your Subject Test needs and plans.

The Harvard web site list two SAT subject test under what a student needs to submit. https://college.harvard.edu/admissions/application-requirements Why are you listing these as optional?

Hi Sally, in this post, we are referencing the letter of Harvard’s Subject Test policy if perhaps not its spirit. Technically, they state clearly that “you may apply without Subject Tests if the cost of the tests represents a financial hardship or if you prefer to have your application considered without them.” In practice, we advise all of our clients who apply to Harvard that Subject Tests are clearly expected. These mixed messages are what the post was highlighting as problematic and confusing. I hope we haven’t simply created more confusion, but ultimately the responsibility for providing more clarity lies with the colleges.