Each October several million sophomores and juniors sit for a PSAT and try to get as few problems wrong as possible. What they may not realize is that College Board, the test’s creator, is trying to do the same thing. The new PSAT has had at least one error every year that the exam has been given. College Board has not treated this issue seriously enough. As we go into another PSAT season, Compass takes a look at what these mistakes mean and don’t mean for students.

Each October several million sophomores and juniors sit for a PSAT and try to get as few problems wrong as possible. What they may not realize is that College Board, the test’s creator, is trying to do the same thing. The new PSAT has had at least one error every year that the exam has been given. College Board has not treated this issue seriously enough. As we go into another PSAT season, Compass takes a look at what these mistakes mean and don’t mean for students.

How many errors have occurred?

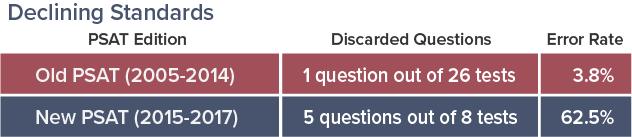

The PSAT is given on two or three dates each year to accommodate different school schedules. In total, there have been 8 new PSAT forms for 2015-2017. Half of those forms had errors on the Math test. The October 19, 2016 form actually had two problems thrown out.

Have these errors always happened?

I wanted to confirm my recollection that the old PSAT rarely had a question omitted from scoring. Between 2005 and 2014, there were twenty-six PSAT dates. On only a single form was a question ever unscored — a Writing question in 2007. Here is how College Board’s performance on the new PSAT stacks up to its performance on the old PSAT.

These results do not inspire confidence.

What causes a problem to be discarded?

An error can be anything from a printing mistake — the diagram on a problem wasn’t completely visible in half of the booklets, perhaps — to a question that accidentally included no correct answer or one that was “double-keyed” and had two correct answers. In one notorious case, College Board included a problem word-for-word taken from practice materials that it had provided students. The solution when errors happen is to not count the question for anyone.

Why have errors become more prevalent?

College Board’s reach has exceeded its grasp. It tried to completely overhaul the PSAT and SAT in a brief period of time and rolled out the new PSAT in October 2015. In doing so, it effectively threw out years of experience developing a certain type of exam and had to start fresh in building a library of material. While making this overhaul, College Board also brought more testing development in-house and reduced its dependency on Educational Testing Service (ETS). College Board likes to fall back on discussing its extensive review and pre-testing process. But a proper review process doesn’t produce this level of mistakes.

How can problems be thrown out and still produce accurate scores?

Built into every test is some level of redundancy. While it’s not good to throw out problems, it does not make the exam invalid.

Imagine a basketball shooting contest involving 48 shots from various points on the court, with one point awarded for each made basket. Would your opinion about the validity of the contest have been different if I had said it involved 47 shots? The ability to make distinctions between skill levels would still be there. That’s basically what happens when College Board discards a problem — the result is to make the test a little shorter. College Board then determines scores based on performance on 47 Math problems rather than 48.

What if one form code has a problem thrown out and another doesn’t?

Some students fear that they are at a disadvantage in having one fewer problem. Multiple form codes must already go through an equating process to account for the fact that question difficulty is never identical from test to test. A model is built, for example, on how a 700 student would perform on one test and how that student would perform on another test. When a problem is thrown out, the model is adjusted to account for it. If done properly, it does not make achieving a particular score easier or harder.

But is it fair?

Still, there is a sense of unfairness in having students take a 48 question test and only grading them on 47 of them. The students who got the discarded question right naturally feel slighted. Looking back to the ranking of basketball players, what if two players originally ended up tied at 25 baskets made. After throwing out one of the attempts — let’s say the lights went out while some of the players were shooting — one contestant ends up with only 24. The rankings were changed. It’s doubtful that either player would have protested at the outset that the contest was only 47 shots rather than 48, but the consequences are real in this case. It’s also problematic in a testing environment because questions are not given in a vacuum. Some students may have quickly answered a discarded item, and some may have labored over it for a few minutes. What if some of the students realized that the problem was flawed and spent extra time scratching their heads? There is not an ideal solution. Giving the test again is not an option anyone wants.

College Board tends to focus on the abstract — 47 questions are enough to produce accurate results. That’s mathematically correct. Students, naturally, focus on the concrete — “I wasted time on a question that didn’t even count!” It makes test takers distrust the test. They literally took a flawed exam.

College Board’s complacency leads to further mistakes. If it doesn’t think it matters whether or not there is an error on a test, it won’t spend the extra time and money to eliminate those errors. On the June 2018 SAT, for example, four questions were omitted from scoring. That’s damaging to a test’s reputation. Moreover, College Board does its best to sweep these mistakes under the rug. It avoids putting the flawed problems in question banks that students can access. Unless its hand is forced, it does not even explain what went wrong with a problem. It threatens students and websites when questions are openly discussed. I have yet to hear any good argument for not revealing why a question was discarded. These are not pre-testing items where College Board is gathering statistical data. These are goofs. If a mistake is made, admit it, explain it, and discuss what steps will be taken to prevent it happening in the future. To the extent that College Board even acknowledges an error, its response is some variation on “Don’t worry, it’s good enough.” I do worry. It’s not good enough. By narrowly focusing on test scoring, College Board overlooks the diminished confidence students, parents, and counselors have in an error-prone exam.

Hopefully College Board will break its PSAT error streak in 2018, and students will know that all of their efforts will be counted. We should all have this expectation and make sure that College Board is accountable if it does not deliver.

It looks like there were two errors in the math section of Oct. 12, 2022 PSAT that my son took

John,

That’s interesting. Does his test show 2 unscored items in Math? It’s unusual that we wouldn’t heard about the errors, but your son may not have taken the primary form.