A Widening Gap

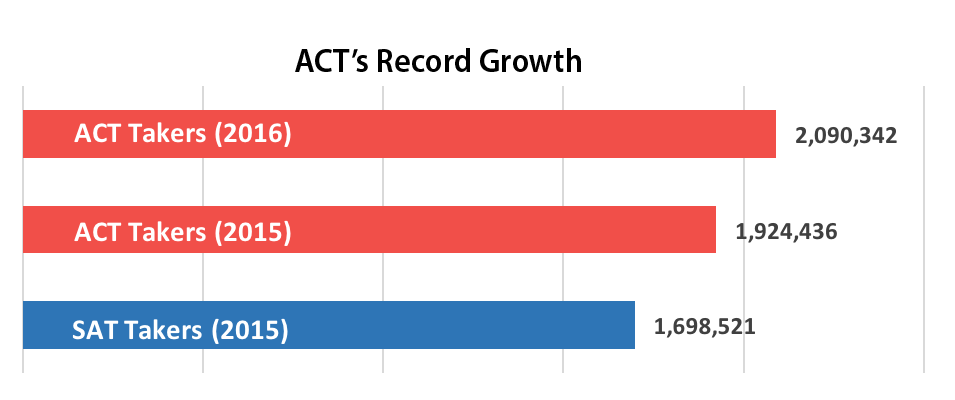

The release of ACT’s class of 2016 report confirms that ACT is now beating College Board where it matters most — everywhere. ACT easily surpassed the 2 million test takers mark. Its gain of 166,000 test takers is the largest in 50 years. The ACT was required of all public high school students in a record 18 states. Twenty-three percent more 2016 graduates took the ACT than took the SAT.

College Board has not yet released its class of 2016 figures, but the SAT is not expected to show more than minimal growth. We’ll use 2015 SAT data as a proxy in this post when making comparisons to the ACT.

If there is a weakness in ACT’s growth engine it is that the gains have been fueled by state-mandated testing. To ensure college readiness for all students and to satisfy federal testing requirements, states are increasingly opting for mandated college admission testing. ACT has had a tremendous head start on College Board, because it could more convincingly make the case that its test was academically aligned.

For the class of 2016, ACT had 18 states where 100% of students were tested: Alabama, Colorado, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, North Carolina, North Dakota, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Wisconsin, Wyoming. That compares to 13 states for the class of 2015.

ACTs 2016 growth was geographically concentrated. Only 6 states had gains or more than 3% of high school graduates, and 5 of those were new mandate states.

State | % of Graduates Tested (2015) | % of Graduates Tested (2016) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska | 39% | 53% | 14% |

| Minnesota | 78% | 100% | 22% |

| Missouri | 77% | 100% | 23% |

| Nevada | 40% | 100% | 60% |

| South Carolina | 62% | 100% | 38% |

| Wisconsin | 73% | 100% | 27% |

For the class of 2017, ACT lost both Michigan and Illinois testing to College Board. Those two states had approximately 270,000 ACT testers in 2016.

The Story of Score Distribution

Compass’ primary interest, though, is not in the business competition between ACT and College Board but in how the numbers impact students, counselors, and colleges. A trend that has accelerated in recent years is the appearance of top scorers on the ACT. Historically, students shooting for the most competitive colleges were wary of the ACT — even well after colleges had made clear that the tests were viewed on equal footing. Students feared an unspoken bias. Ironically, the competitiveness of admission at top colleges that once created hesitation is now driving students to the ACT. Students and parents are loathe to leave any stone unturned when presenting a positive testing portfolio. Hitting 25 home runs from the right side of the plate is great until you realize that you are a lefty who can hit 40 home runs from the other side.

While many students perform similarly across the admission tests, some find a marked advantage in one test over the other. That advantage can be a higher score, of course, or the advantage could be in the form of easier preparation and reduced anxiety from material that feels more natural.

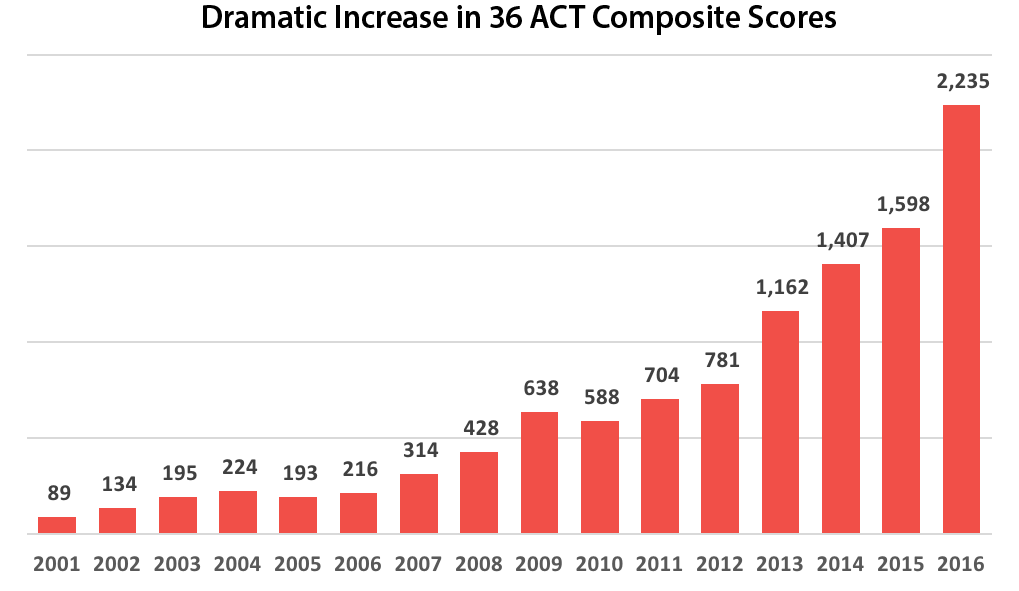

Perhaps the most remarkable change in recent years is the rise of the 36 Composite. In 2001, only 89 students received a perfect score on the ACT. That represented 1 student out of every 12,000 tested! The score barely existed. In 2016, there were a record 2,235 perfect Composite scorers or 1 of every 935 testers. Even just looking at the last 4 years, the number of perfect scores has nearly tripled. And these were students who tested prior to the debut of a mysterious new SAT. It’s likely that avoidance of the new SAT in the class of 2017 will bump the number of perfect ACT scores even higher this year.

Why was the number so low, and why has it gone so high?

The change was not manufactured by the ACT itself — the test difficulty has not changed over the last 15 years. (We are regularly disappointed at how many of our colleagues in the test prep industry argue the opposite side of fundamental questions such as this. They are simply mistaken, and we have tried to present the facts plainly and clearly in the remainder of this post.) The difference is in the pool of students choosing to take the ACT. Even in states where most students favored the ACT, top scoring students 10-15 years ago opted for what they considered the safety of the SAT. What changed is that a lot more students decided to at least try hitting from the left side of the plate.

Common Questions

When discussing these sorts of changes, some common questions arise:

Did ACT make the test easier in order to attract more students?

Changing a test’s difficulty — meaning how hard it is to get a particular score — requires changing how a test is scaled. This is done infrequently (ACT last made a change in 1989) and with great notice (ACT and SAT typically start educating students and counselors 2-3 years before a change is made and are open about how old and new scores should be compared). Scores that change behind the scenes would devalue the test. A college would have no way of accurately comparing scores. States and school districts would have no way of tracking student performance over time. Consistency and comparability are what give the ACT and SAT power. If the test were getting easier, we would see significant score changes in states and districts that already had a high penetration of students taking the exam. That has not been the case.

Isn't the ACT making the test harder to account for the fact that more top students are taking the test?

This is the inverse of the first question, and most of the answer still applies. ACT is not benefited or harmed whether there are one thousand 36s or three thousand 36s. If it suddenly had ten thousand 36s, then something would have gone wrong with the test, and it would clearly be losing its ability to discriminate among top students. What is actually happening is that ACT and SAT are more in balance than they have ever been. At the higher end of the score ranges in 2016, the testing populations have become similar.

Doesn't the fact that more top students are taking the ACT change the curve?

No, that’s not how a curve is established on the ACT. The SAT and ACT use a fixed reference group to norm scores when the initial scale is created. After that, every new test is equated back through an unbroken chain that leads to this reference group. The ACT is, after all, simply an academic measuring stick. A measuring tape doesn’t need to get longer or shorter based on whether I am measuring the height of third-graders or NBA players.

Hasn't the ACT made the questions harder recently to account for more high scorers?

This question deserves — and will receive — a post of its own. The material covered by the ACT evolves with the academic standards used by states (in recent years, the Common Core State Standards). In some cases, the material added is more advanced. This does not necessarily lead to harder questions. The difficulty of a question is highly dependent on the clues an item writer provides and on the ways in which the correct answer is disguised. Slightly more difficult questions can be offset with slightly easier questions. ACT has no interest in “competing” with students in trying to stump them. The increase in high scores is the most obvious evidence that ACT is not trying harder to “stump” students. The test allows for slow and steady content evolution while keeping the measuring stick intact.

Now that high scores are becoming commonplace on the ACT, shouldn't I switch to the SAT?

Does hitting a left-handed home run score more runs than hitting a right-handed home run? Taking a standardized test is not like trying to stand out by playing the tuba or winning a national writing contest. Top colleges will have thousands or tens of thousands of ACT and SAT scores to compare and have a number of ways of doing that in a consistent fashion. Receiving more or fewer ACT scores does not change the relative value of a top score. It should also be pointed out that most top colleges still see more SAT scores than ACT scores. The gap is narrowing quickly, but the change is far from dramatic enough to impact their decision making. Concordance tables are used to compare ACT, old SAT, and new SAT scores and are not dependent on whether you choose to take the ACT or the SAT. Students should take the test that suits them best. In many cases, the score differences are trivial. Students need not take ACT or College Board administered tests to identify a preferred exam. Taking previously released exams in a proctored environment can replicate the experience without putting a score on the student’s record. The PreACT, Aspire, and PSAT can also serve as reference points. Switch based on how you will prepare and perform, not on a test’s popularity.

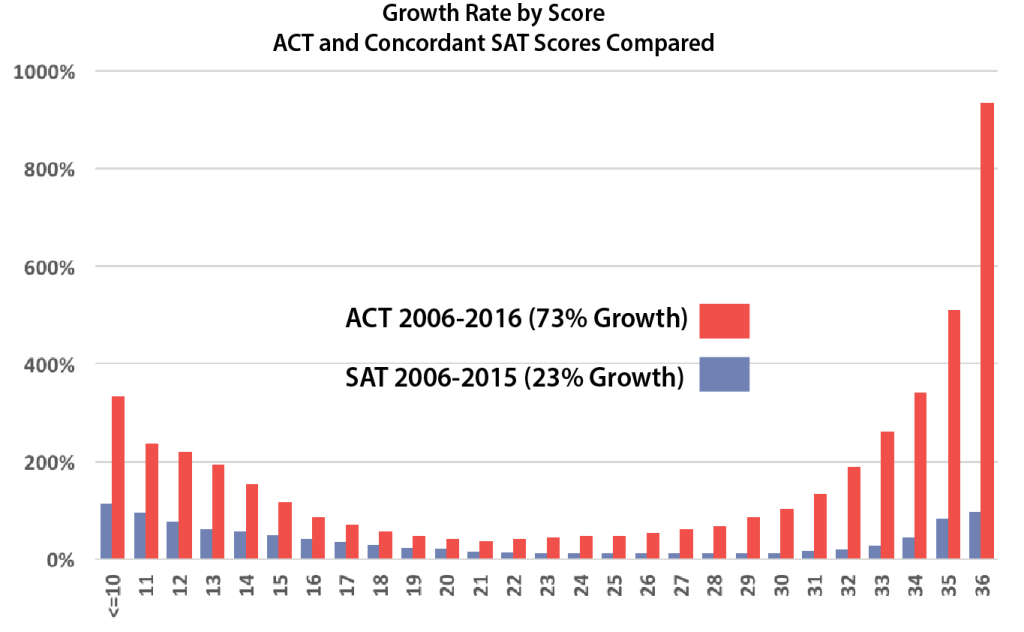

Change at All Levels

Although the change is most pronounced at the top score, the trend is present throughout the high score range. The lowest scores also increased much higher than the average increase overall. The cause at the low end is quite directly the increase in state-funded testing. By testing all students, states have included students who might not ordinarily be ready for 4-year colleges and would not have taken the ACT on their own. In the graph below showing concorded SAT scores that fall on the same 1-36 scale as ACT scores, it becomes obvious that SAT is losing the growth game, particularly at the extremes.

While the growth at the low end is easy to pin down, the increase in high scoring students is more multifaceted.

- State-funded testing is leveling the playing field between the ACT and SAT among students applying to the most competitive colleges.

- Increased ACT testing in states that traditionally produce a disproportionate share of top scorers.

- Heightened attention to ACT test preparation and repeat testing.

- A shift toward “dual testing” for students looking at competitive colleges.

Based on our analysis of the numbers and our understanding of the landscape, we believe that the last point has had the biggest impact. Despite the increase in top ACT scores, the number of top scoring SAT testers did not decline. So where did the students come from? The first three factors don’t do enough to explain the strength and rapidity of the change.

State-funded testing clearly played a large role, but it does not explain the hyper-growth at the high end. Universal testing has little impact on the absolute number of top scoring students in a state, since those students are already taking admission tests. What it did do was generate equal consideration of the SAT and ACT among students and catalyze the trend toward dual testing.

If ACT were simply taking market share away from the SAT, we would be likely to see decreases in SAT testing (the growth in college attendance is moderate). Yet at each score swath, we see SAT gaining students over the last decade.

| SAT Range | Concordant ACT Range | Students 2006 | Students 2016 | Student Growth 2006 - 2016 | % Growth 2006-2016 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2140-2400 | 33-36 | 33,599 | 47,466 | 13,867 | 41% | ||

| 1920-2130 | 29-32 | 115,708 | 132,519 | 16,811 | 15% | ||

| 1680-1910 | 25-28 | 270,326 | 300,926 | 30,600 | 11% | ||

| 1450-1670 | 21-24 | 379,933 | 430,167 | 50,234 | 13% | ||

| 1210-1440 | 17-20 | 359,607 | 454,705 | 95,098 | 26% | ||

| 600-1200 | <=16 | 217,572 | 332,738 | 115,166 | 53% | ||

| Total | 1,376,745 | 1,698,521 | 321,776 | 23% |

We presented the chart of ACTs percentage gains earlier in this post. The table below shows how those gains are reflected in student numbers.

| ACT Range | Concordant SAT Range | Students 2006 | Students 2016 | Student Growth 2006 - 2016 | % Growth 2006-2016 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33-36 | 2140-2400 | 13,235 | 57,005 | 43,770 | 331% | ||

| 29-32 | 1920-2130 | 77,648 | 166,631 | 88,983 | 115% | ||

| 25-28 | 1680-1910 | 202,353 | 314,949 | 112,596 | 56% | ||

| 21-24 | 1450-1670 | 334,666 | 475,482 | 140,816 | 42% | ||

| 17-20 | 1210-1440 | 352,700 | 539,470 | 186,770 | 53% | ||

| <=16 | 600-1200 | 225,853 | 536,805 | 310,952 | 138% | ||

| Total | 1,206,455 | 2,090,342 | 883,887 | 73% |

For scores that would have been approximately 80th percentile and above in 2006, there are 240,000 SAT and ACT takers. If we look at equivalent scores from 2016, 404,000 students achieved those scores. That’s a 68% change over a period where the number of high school graduates increased by less than 5%. Returning to the baseball metaphor, students batted left-handed and right-handed in order to find their best swing. These dual testers now regularly sample both exams. Nationwide, we estimate dual testing at 35-45% among high scoring students. At the most competitive independent and public schools, we see dual testing rates closer to 65-75%. Tempering those numbers for the class of 2017 has been avoidance of the new SAT entirely by many students. The long-term trend, though, is likely to stay. Only a handful of colleges require students to submit all SAT and ACT scores taken, so families feel empowered to experiment. Score Choice and superscoring policies generate further enthusiasm for dual testing.

Over-testing and the dissipation of energy across multiple tests is a concern that we communicate to families. Choosing the most appropriate exam is important, but game day situations can be replicated. Taking released exams under proctored conditions can give an accurate read of a student’s strength. The PreACT, Aspire, and PSAT provide additional data points. Still, many families cannot resist trying both tests officially.

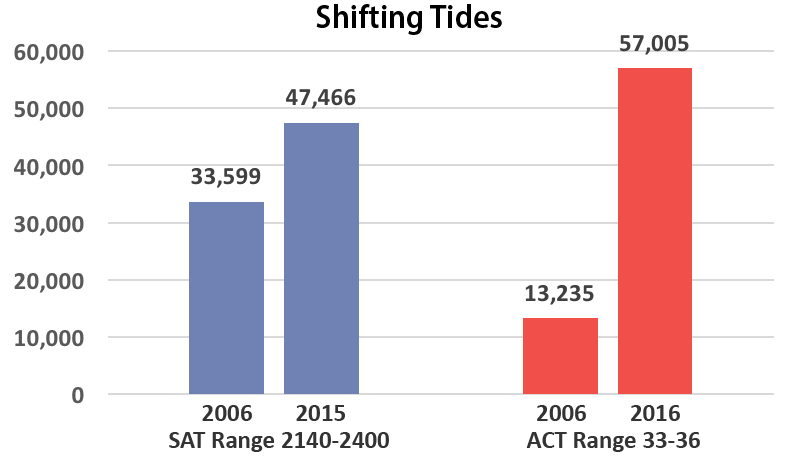

Laggard to Leader

Both the ACT and SAT have made gains, but scale of the gains is far from equal. Among students scoring 33-36 on the ACT (comparable to 2140-2400 on the old SAT), for example, ACT went from a large disadvantage to a modest advantage.

How similar are SAT and ACT takers?

A tempting and common mistake students make is mixing and matching of percentiles across exams in order to judge results. PSAT percentiles are not the same as SAT percentiles. SAT percentiles are not the same as ACT percentiles. Nothing is the same as Subject Test percentiles. The reason these alignments fail is that the tests are taken by different populations. And even within the same exam, trends make comparisons risky over time. For example, as recently as 2008, a 32 Composite on the ACT was the 99th percentile. A student must now get a 34 to reach the 99th percentile. This is a concept that is hard to accept: the meaning of a 34 didn’t change, only the group of testers did.

An interesting offshoot of ACT’s gains is that percentiles for above average students are closer to comparable SAT percentiles than they were in the past. Below is a table showing how ACT test taker figures stacked up against SAT figures for 2006 and 2016.

| ACT Range | Concordant SAT Scores | ACT Takers as % of SAT Takers (2006) | ACT Takers as % of SAT Takers (2015/16) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 33-36 | 2140-2400 | 39% | 120% |

| 29-32 | 1920-2130 | 67% | 126% |

| 25-28 | 1680-1910 | 75% | 105% |

| 21-24 | 1450-1670 | 88% | 111% |

| 17-20 | 1210-1440 | 98% | 119% |

| <=16 | 600-1200 | 104% | 161% |

| Total | 89% | 123% |

The differences in 2006 were highly skewed. While the tests had parity at scores 20 or below (600-1440 old SAT), ACT had far fewer testers in the upper ranges. By 2016, two things had happened: 1) ACT led in student numbers at each range, and 2) the differences between ranges had greatly narrowed. This makes, temporarily, SAT and ACT percentiles roughly comparable for above average scores. Unfortunately, the reordering of testing patterns with the new SAT will likely make this quick comparison risky again. We still recommend the use of concordance tables when comparing scores (see https://www.compassprep.com/concordance-and-conversion-sat-and-act-scores/).

Percentiles can also be misrepresentative because they don’t reflect a student’s fellow applicants at Grinnell or San Diego State or UCLA or Brown. Comparing one’s absolute scores to the 25th-75th range for first year students is a better method for assessing how “good” one’s scores are. [An even truer measure is how one stacks up in the range of applicants and range of admitted students, but most colleges only report these figures for students who actually enroll.]

In prior years, Compass would have advocated against directly comparing percentiles for the two exams. Concordance tables are still the most reliable way of making comparisons, but the percentile shortcut is now far accurate than it was even a few years ago. The test taking pools are almost identical at the top of the score range.

| ACT Score | Concordant SAT Score | SAT Percentile 2015 | ACT Percentile 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 2380–2400 | 100 | 100 |

| 35 | 2290–2370 | 99.9 | 99.8 |

| 34 | 2220–2280 | 99.3 | 99.3 |

| 33 | 2140–2210 | 98.5 | 98.4 |

| 32 | 2080–2130 | 97.2 | 97.2 |

| 31 | 2020–2070 | 95.7 | 95.7 |

| 30 | 1980–2010 | 93.7 | 94 |

| 29 | 1920–1970 | 92.2 | 91.8 |

| 28 | 1860–1910 | 89.4 | 89.3 |

| 27 | 1800–1850 | 85.9 | 86.3 |

| 26 | 1740–1790 | 81.8 | 82.7 |

| 25 | 1680–1730 | 77 | 78.7 |

| 24 | 1620–1670 | 71.6 | 74.2 |

| 23 | 1560–1610 | 65.7 | 69.1 |

| 22 | 1510–1550 | 59.2 | 63.5 |

| 21 | 1450–1500 | 53.4 | 57.6 |

| 20 | 1390–1440 | 46.3 | 51.4 |

| 19 | 1330–1380 | 39.1 | 45.1 |

| 18 | 1270–1320 | 32.1 | 38.7 |

| 17 | 1210–1260 | 25.5 | 32.1 |

| 16 | 1140–1200 | 19.5 | 25.6 |

| 15 | 1060–1130 | 13.7 | 19.4 |

| 14 | 990–1050 | 8.5 | 13.6 |

| 13 | 910–980 | 5.3 | 8.3 |

| 12 | 820–900 | 2.8 | 4.1 |

| 11 | 750–810 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| <=10 | <=740 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

Carrying on your baseball analogy, is anyone marginally impressed by switch hitters?

Ethan,

I assume that you mean, “Will colleges give extra points to an applicant with high SAT and high ACT scores?” I’ve never heard this to be the case. The two exams measure largely the same skill — hitting. To see if students can pitch, run, and catch, colleges need to turn to other tests such as Subject Tests, APs, or IBs. These are particularly important for the homeschooled student, since the number one scouting tool — GPA — carries more uncertainty.

I have read frequently in college admissions materials that there is no preference by colleges for a certain test. Is this still true? Do these results change that axiom? Do they just say that and not really mean it?

Megan,

Colleges have found that the SAT and ACT give them essentially the same level of information about a student. They would be foolish to alienate or underweight the 40% of students who only take one test or the other. Competitive colleges are far from foolish [except those that require the essay!]. There is no preference given to either test. The changes we are seeing in market share are the result of a) students finally believing this b) state contracts and c) dual testing.

Thank you , Art. One follow up question. Do you think that smaller private liberal arts colleges prefer the SAT over the ACT? Again, in the materials I read they state that they do not, but I would like to know your expert opinion. Conversely, do you think that large state universities such as the University of Texas prefer the ACT? Thanks again.

Megan,

No, there is no preference difference among private LACs and public universities. Colleges have varying sources of applicants, so some receive more ACT scores than SAT (or vice versa), but they do not favor one over the other. Most colleges, in fact, use concordance tables to make scores comparable.

Thank you, Art!

I just discovered that schools and other organizations now have to pay to order ACT student booklets. I was curious if you’d heard about this and know any details about why. Thank you.

Karia,

If you are referring to the Preparing for the ACT booklet that counseling offices typically distribute, then I have not heard that. On the online ordering page, ACT does ask “before ordering printed materials…help us go green.” I don’t see anything about new fees, however. Students can, of course, download the free PDF. If you are referring to the test booklets of old exams that ACT sells at a discounted rate to schools, then I believe they are continuing the same practice of charging for booklets.

Thank you, Art. I believe I had two confused.

Nice article! I say that as a well-known economics professor.

I was googling, though, hoping to find out why the ACT has been beating the SAT over the past decade or whatever. That’s not your main interest, but it’s surely relevant. One reason, as you say, is that rich students are taking both now instead of just the SAT. Related to that is that the college market is becoming ever more national. But why, for example, has ACT been able and willing to make its test academically more attractive in mandatory states? Are there also price differences? Is ACT a nimbler, better-managed, company? Is it less ideological?

Eric,

Thank you.

That’s a topic I have followed with interest. Much of it boils down to a changing education landscape finally coming around to ACT’s view of the world. Since its start in the 1950s, ACT has always had a focus on academic alignment (you can see an example of how they tie the test to state standards here). That was not a strong selling point when college admission testing was its own separate world. The SAT could use oddball items like Quantitative Comparisons or antonyms not because they had some important academic merit but because the items did a good job at predicting college success. The shift that has happened over the last two decades in testing has been the rise of achievement or alignment over aptitude — the latter becoming something of a dirty word. College Board kept trying half-measures by modifying the SAT (and its name) multiple times, but the exam had a difficult time shedding its reputation as an aptitude test. The tipping point came with NCLB and Race to the Top initiatives where states and districts were required to implement additional student testing. ACT saw this as an opening to pitch its test as both a college admission test (opening access to college for 100% of graduates) and a summative test to satisfy DOE (state and Federal) needs. ACT, the test, was better positioned for this sale versus the SAT; ACT, the organization, was more effective in pitching legislatures (ironic, since College Board was being led by a former governor). By the time Common Core became a reality, ACT was in the dominant position, and College Board had to play catch-up.

I wouldn’t call either organization nimble. ACT was at the right place at the right time. Pricing has always been roughly comparable. In one notable case, Michigan got stolen away by College Board because ACT thought that they had things locked up. College Board came in with more aggressive pricing (largely by dropping many of the “extras”) and got buy-in from the state that the new test would check off the right academic boxes (something that surprised ACT). Institutionally, AP became the golden goose at College Board, so there is no doubt that they ignored the problems with the SAT for too long. It’s not surprising that College Board turned to a Common Core architect (David Coleman) when hiring a new president. In having to do a massive overhaul under intense time pressures, though, things may have become worse for the SAT until they get better. We are unlikely to ever see a world again in which 99% of applicants to a college take the same exam (as was the case with the SAT even after colleges were, theoretically, accepting the ACT).

Thank you for the article. The comparison and the analysis were thorough. If you would, please explain why you see little value in the optional writing assessment (per the comment above).

Joshua,

It’s difficult to summarize in a couple of sentences. Since your professional experience is in this area, I feel free to give an expanded explanation. {I know that ACT now labels the test as “writing,” but I prefer to distinguish it as Writing.]

Constant Change and Confusion

The repeated changes by ACT have been problematic for students and colleges. In September 2015, of course, ACT introduced a new task and a new rubric and placed scores on the 1-36 scale. The 1-36 scoring was a disaster in both consistency and score readiness. One result, I believe, was the firing of the company handling the essay grading. Despite ACT’s defense of the 1-36 scoring, it proved untenable. Yet the scaling was not entirely eliminated, since the Writing score is still folded into the 1-36 ELA score. I admit that I find both the ELA and STEM scores to be marketing gimmicks that further confuse students. ACT also decided that its policy allowing for essay regrading was unwise, so it dropped this option (the fact that ACT was offering so many refunds when scores changed likely played a role).

A New Task

More recently, ACT changed the “task” for the essay. While its online materials reflect this change, the most recent edition of The Official ACT Prep Guide — which was just published — retains the old task. I find this incredibly misleading to students who think they are properly preparing for the exam by purchasing the “official” guide.

Rampant Over-testing

My biggest complaint is that of over-testing. Approximately 1.3M students in the class of 2016 took ACT w/Writing. A very low-end estimate would be that those students did 2M essays (multiple test dates). For the most recent academic year, the essay added $16 to the base fee of $42.50. In other words, it increased costs to students (or districts or states) by 38%. The 40-minute Writing section is actually longer than Reading and Science and increases test length by about one-fourth. ACT has provided scan evidence that the added testing improves outcomes.

Few Colleges Maintain Writing Requirements

With the switch to an optional essay on the SAT, more and more colleges began dropping requirements for ACT Writing. Of a set of 360 of the most competitive colleges, we show that currently 27 (7.5%) require Writing. [The data on ACT’s own website is typically outdated by several years.] We also find that very few of the least competitive colleges require Writing. The disparity between the number of students who need to submit a Writing score versus those who take the Writing test is too extreme to ignore. While it is true that many students take Writing in the event that they choose to apply to the small set of requiring colleges, it is also true that a small minority of colleges are driving a $30M+ business that benefits few. Because I have to ensure that students stay eligible for colleges such as the UC’s, I have no choice but to advise students to take Writing. I admit that I find this distasteful.

I place value on good writing. At one point in my life, I wasn’t all that bad at writing. As a tutor, I often had my most enjoyable sessions working with students on improving their SAT and ACT essay skills. There is nothing inherently objectionable about evaluating writing as part of standardized testing. In my opinion, the testing organizations have not yet shown that they can do it in a manner that is consistently valid or that adds sufficient value to the admission process to justify the costs and anxiety involved.

Hi Art.

I have a more general question about the ACT. The second time I took it, I got a perfect score on one of the sections, but the first time my composite score was higher. When applying to colleges, can I say my composite score was 34 and also I got a perfect score on one section- just not on the same test? I know the ACT doesn’t superscore like the SAT, so how would this work?

Always appreciate your articles, I’m a huge fan!

Jack,

Colleges are the ones who make decisions about superscoring. Over the last 5 years, we’ve seen more colleges fall into that camp (you can find the list here). For those cases, you’d want to submit both scores. You can’t pick and choose individual scores from within a test date. You send all April scores and all June scores, for example. If a college does not superscore, it may still be to your advantage. Most colleges have policies of viewing scores in the most favorable light (so taking the highest composite). In those cases, a lower composite won’t hurt you, but seeing a 36 might help you. If there is a big gap between your composite scores (let’s say 31 and 34), then I would absolutely send only the better test date. A somewhat higher score on a single section is unlikely to change things.

And thank you for the kind words.

My son got a 30 the first attempt, and a 33 in his second attempt. He went up in 3/4 sections by a lot, but math went down from 34 to 32 ( he got 33 in all other 33 sections). Should he send both because math was higher the first time, or do we not worry and just send the best score?

Also he is happy with his score, but is there an advantage in taking the SAT as well or can he be done testing?

thanks

Michele,

Congratulations to your son on his improvement. In your son’s case, I would just send the best scores. Some schools will superscore the ACT (make a new composite from the best section scores), but your son would still have a 33 composite superscored. I would not recommend a switch to the SAT for someone already scoring that well on the ACT. I’m glad to hear that he is happy with his score. If he changes his mind, I’d recommend that he stick with the ACT.

Art,

Thank you for the great article.

I have been looking around the web to get an understanding of my ACT score of 33. Most schools publish the mid 50% range but it is hard to find distribution data on that 50%. Is it skewed given the % of scorers reduce as one moves up on the scale?

Would it possible for you share your opinion of whether this score will increase/decrease my admission chance while applying to engineering colleges at top schools (including Ivies).

Vijay,

We can’t use the distribution of all testers to tell us much about the distribution at a particular college. There are also a number of problems in thinking of an ACT score “percentile.” The biggest problem is that ACT scores are correlated with GPA. For example, does a 36 composite is better than a 34 composite, but how much better is obscured by the fact that 36 scorers tend to have higher GPAs than 34 scorers. Now that we’ve got some of the caveats out of the way, let’s look at some numbers.

Although not known as an engineering school, Brown provides nice data because not only do they give a breakdown by score range (in thinner slices than most), they give figures for applicants, acceptances, and enrollments. Rather than duplicate everything here, I’ll provide the link.

As you can see, students with 36s have the highest acceptance rate (this is almost universally true). The largest cluster of students, though, fall in the 29-32 and 33-35 buckets. If I estimate curves for applicants and acceptances (back of envelope), I get something as follows:

36, 464, 132, 28%

35, 1500, 273, 18%

34, 2607, 261, 10%

33, 2607, 235, 9%

<33, 9146, 528, 6%

Total, 16324, 1429, 9%

My back of the envelope figures show that 33 is pretty close to the middle in terms of acceptance rate and the number of accepted students above and below that mark. It also shows -- keeping in mind my caveats above -- that it is likely that a student scoring above a 33 can improve his or her chances. This is not exactly a surprising conclusion. All things being equal, a higher score is better. A 33 is an extremely good score when looking at the population of test-takers. It is an average score when looking at accepted students at elite colleges. You'll notice that I skipped the leap from acceptances to enrolled. Most colleges report enrolled figures. Those numbers will be slightly lower than they are for accepted students, because the higher an admit's score, the greater the chance that the admit has better options elsewhere (we see this universally and is no way meant as a knock on Brown). Another thing to keep in mind is that the overall figures include "hooked" students such as athletes or legacies. An unhooked student should expect to need higher scores. I would recommend trying to boost your ACT score given your target colleges.

Art, thank you for this post. Very interesting. May I ask what you will think will happen to the SAT/ACT concordance tables this summer? There have been discussions online predicting that the NEW SAT will move up 10-20 points in the higher end of the concordance table. For example, a 34 will equal 1500. What is your guess? Do you think it will move more than that?

Thanks!

Tina,

I consider myself something of a concordance connoisseur, but I’d have to say that there is not enough valid, public data on which to make a guess. Your example would be true if students are slightly underperforming on the new SAT compared to where College Board predicted they would perform. I do believe that changes are likely to be fairly narrow — in the 10 to 20 point range. Hopefully we won’t have to wait much longer!