Record High National Merit Scores Announced

Every year, the National Merit Scholarship Program honors approximately 17,000 students as National Merit Semifinalists based on junior year PSAT scores. Semifinalists can continue in the competition to become Finalists and, potentially, scholarship recipients. Current Semifinalists and future participants may want to read Compass’s National Merit Scholarship Program Explained for more information on the steps in the program. An additional 40,000 students are honored as Commended Students for having scores in the top 3% of all test takers. The recently confirmed cutoffs reveal that the Class of 2026 had the highest Semifinalist scores ever on the PSAT. Of the 12 largest states, 8 set new records and the other 4 tied their highest historical marks. Students in Massachusetts and New Jersey (225) would have needed to score at least a near-perfect 750 on the Reading & Writing (RW) and combine it with a 750 or 760 on Math.

The large jump points to a problem

The nearly universal increase in Selection Index cutoffs is most likely attributable to a flaw in scaling or test construction that produced higher scores on both Reading & Writing and Math. Since these sorts of scoring changes can also occur on the SAT, this post explores the implications for National Merit and college admission testing.

Scaling error best explains:

- Why there were changes across the entire score range

- Why there was a change in almost all states

- Why new records were reached in so many states, particularly the largest states

It’s the sort of shift we have seen before, but there are some added twists this time.

How cutoffs are determined

Qualifying scores (“cutoffs”) are not based on the total score for the PSAT (360-1520) but on the Selection Index, which is calculated by doubling the RW score, adding the Math score, and then dividing the sum by 10. The maximum Selection Index is 228. Students can find a historical set of cutoff data here or see how Semifinalist and Commended counts have changed state by state.

Semifinalists are allocated by state, and cutoffs are calculated by state. This means that students across the country face varying qualifying scores for Semifinalist status (the Commended level is set nationally). The cutoffs for the Class of 2026 range from 210 in New Mexico, North Dakota, West Virginia, and Wyoming to 225 in New Jersey and Massachusetts. If California is allocated 2,000 Semifinalists based on its population of high school graduates, then NMSC works down from a perfect 228 Selection Index until it gets as close as possible to that target. This year, California’s 224 included 2,172 students. A cutoff of 225 would have produced too few Semifinalists. A cutoff of 223 would have gone well over the allocation.

Below are this year’s cutoffs compared to those from prior years. The Class of 2026 figures are confirmed.

| State | Class of 2026 (Actual) | Change | Class of 2025 (Actual) | Class of 2024 (Actual) | Semifinalists | Commended |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 214 | 2 | 212 | 210 | 228 | 141 |

| Alaska | 215 | 1 | 214 | 209 | 31 | 24 |

| Arizona | 218 | 1 | 217 | 216 | 409 | 557 |

| Arkansas | 215 | 2 | 213 | 210 | 141 | 106 |

| California | 224 | 3 | 221 | 221 | 2172 | 6840 |

| Colorado | 219 | 1 | 218 | 216 | 287 | 579 |

| Connecticut | 223 | 2 | 221 | 221 | 193 | 709 |

| Delaware | 220 | 1 | 219 | 219 | 47 | 84 |

| Florida | 219 | 2 | 217 | 216 | 1008 | 1824 |

| Georgia | 220 | 2 | 218 | 217 | 620 | 1243 |

| Hawaii | 219 | 2 | 217 | 217 | 60 | 124 |

| Idaho | 215 | 2 | 213 | 211 | 90 | 76 |

| Illinois | 222 | 2 | 220 | 219 | 748 | 1888 |

| Indiana | 218 | 1 | 217 | 216 | 333 | 531 |

| Iowa | 214 | 2 | 212 | 210 | 138 | 77 |

| Kansas | 216 | 1 | 215 | 214 | 136 | 113 |

| Kentucky | 214 | 1 | 213 | 211 | 200 | 121 |

| Louisiana | 216 | 2 | 214 | 214 | 220 | 219 |

| Maine | 217 | 3 | 214 | 213 | 57 | 63 |

| Maryland | 224 | 2 | 222 | 221 | 348 | 1290 |

| Massachusetts | 225 | 2 | 223 | 222 | 282 | 1754 |

| Michigan | 220 | 2 | 218 | 217 | 470 | 965 |

| Minnesota | 219 | 2 | 217 | 216 | 266 | 438 |

| Mississippi | 213 | 1 | 212 | 209 | 153 | 53 |

| Missouri | 217 | 2 | 215 | 214 | 281 | 326 |

| Montana | 213 | 4 | 209 | 209 | 48 | 8 |

| Nebraska | 214 | 3 | 211 | 210 | 109 | 63 |

| Nevada | 214 | 0 | 214 | 211 | 185 | 78 |

| New Hampshire | 219 | 2 | 217 | 215 | 51 | 99 |

| New Jersey | 225 | 2 | 223 | 223 | 511 | 3199 |

| New Mexico | 210 | -1 | 211 | 207 | 111 | 0 |

| New York | 223 | 3 | 220 | 220 | 992 | 3378 |

| North Carolina | 220 | 2 | 218 | 217 | 523 | 1151 |

| North Dakota | 210 | 0 | 210 | 207 | 26 | 0 |

| Ohio | 219 | 2 | 217 | 216 | 490 | 999 |

| Oklahoma | 212 | 1 | 211 | 208 | 214 | 39 |

| Oregon | 219 | 3 | 216 | 216 | 188 | 318 |

| Pennsylvania | 221 | 2 | 219 | 219 | 612 | 1511 |

| Rhode Island | 219 | 2 | 217 | 215 | 50 | 96 |

| South Carolina | 215 | 1 | 214 | 209 | 225 | 197 |

| South Dakota | 211 | 3 | 208 | 209 | 46 | 6 |

| Tennessee | 219 | 2 | 217 | 217 | 306 | 521 |

| Texas | 222 | 3 | 219 | 219 | 1673 | 4653 |

| Utah | 213 | 2 | 211 | 209 | 199 | 68 |

| Vermont | 216 | 1 | 215 | 212 | 27 | 27 |

| Virginia | 224 | 2 | 222 | 219 | 489 | 1912 |

| Washington | 224 | 2 | 222 | 220 | 388 | 1295 |

| West Virginia | 210 | 1 | 209 | 207 | 66 | 0 |

| Wisconsin | 215 | 1 | 214 | 213 | 287 | 216 |

| Wyoming | 210 | 1 | 209 | 207 | 20 | 0 |

| District of Columbia | 225 | 2 | 223 | 223 | 37 | 230 |

| Boarding Schools | 220-225 | 158 | 652 | |||

| U.S. Territories | 210 | 2 | 208 | 207 | 43 | 0 |

| Studying Abroad | 225 | 2 | 223 | 223 | 86 | 565 |

| Commended | 210 | 2 | 208 | 207 |

What the PSAT tells us about the SAT

Analyzing the PSAT/NMSQT is about more than just explaining National Merit cutoffs. The PSAT also provides a unique window into the SAT program. National Merit results offer comparable year-over-year data that are more granular than what College Board provides for the SAT. The scoring anomalies we saw on the October 2024 PSAT are also likely occurring on the SAT; they’re just better disguised on the three-letter exam. Based on our historical review, scoring outliers crop up every 3 to 4 years with the PSAT. Projected across an SAT cycle, that’s potentially 2 problematic exam dates every year!

Cutoff changes

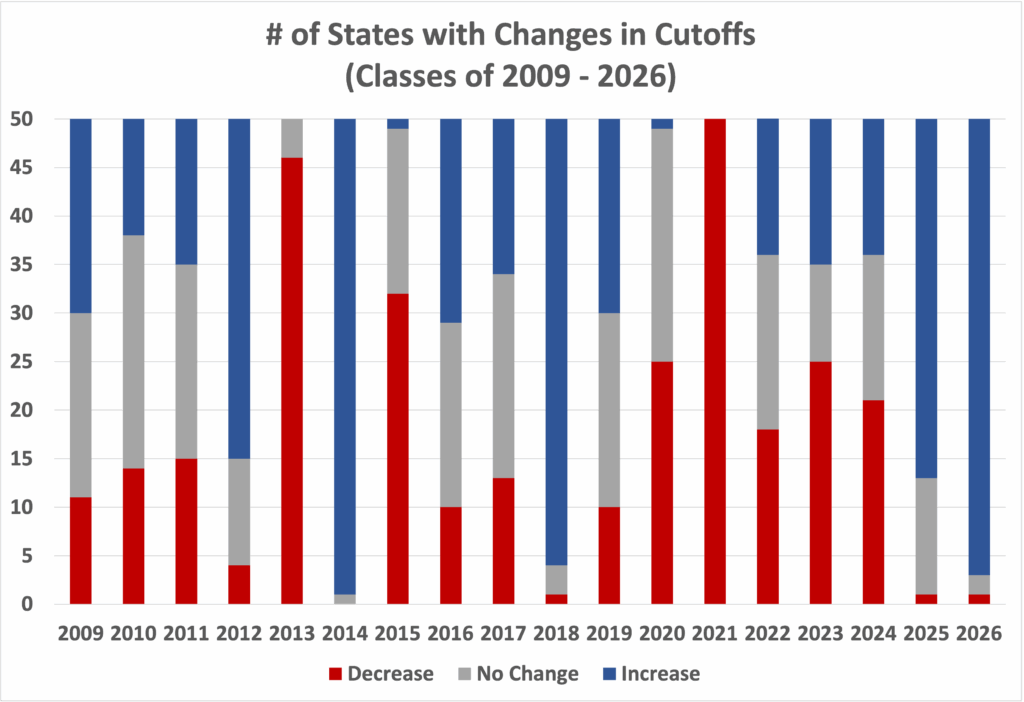

In total, 47 states saw higher cutoffs, as did the District of Columbia (225, a new record), U.S. territories and commonwealths (210), U.S. boarding schools (220-225, new records), and U.S. students abroad (225, a new record). Boarding school cutoffs are set at the highest state cutoff within the National Merit region. For students at day schools, eligibility is defined by the school’s location rather than the student’s home address.

State cutoffs always have some degree of fluctuation, especially in smaller states. The size and consistency of this year’s movements set them apart, and large states provide the best measuring stick. A 3-point increase in Maine’s cutoff might be considered unusual, but a 3-point rise in California’s cutoff demands an explanation.

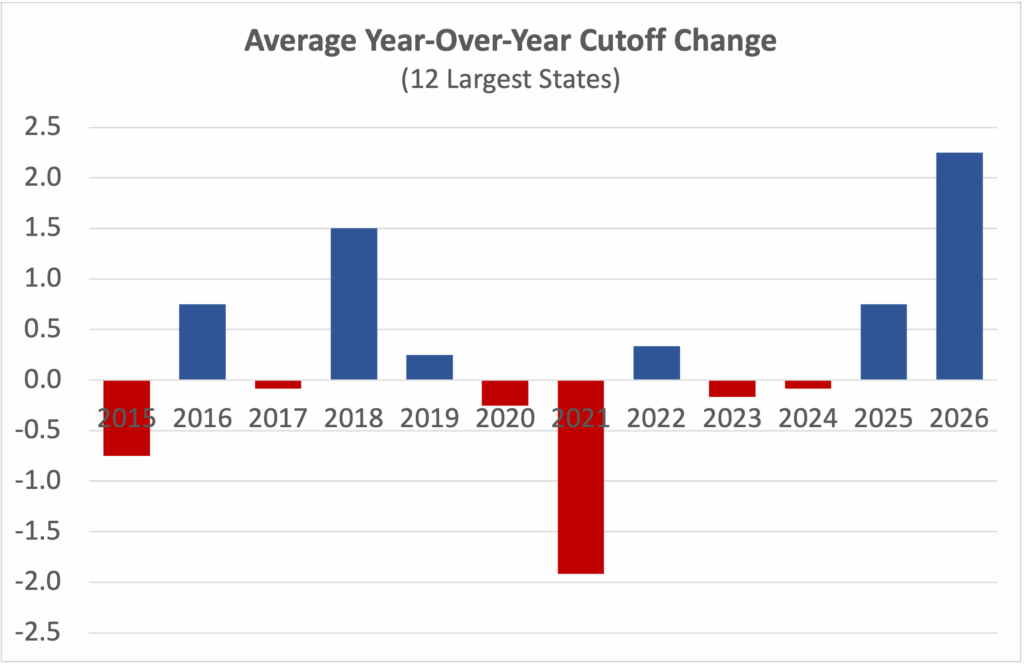

The 12 largest states account for more than 10,000 Semifinalists. Their cutoffs went up an average of 2.25 points, a record change. Even the plunge in the Class of 2021, traced back to a flawed PSAT form, was more moderate.

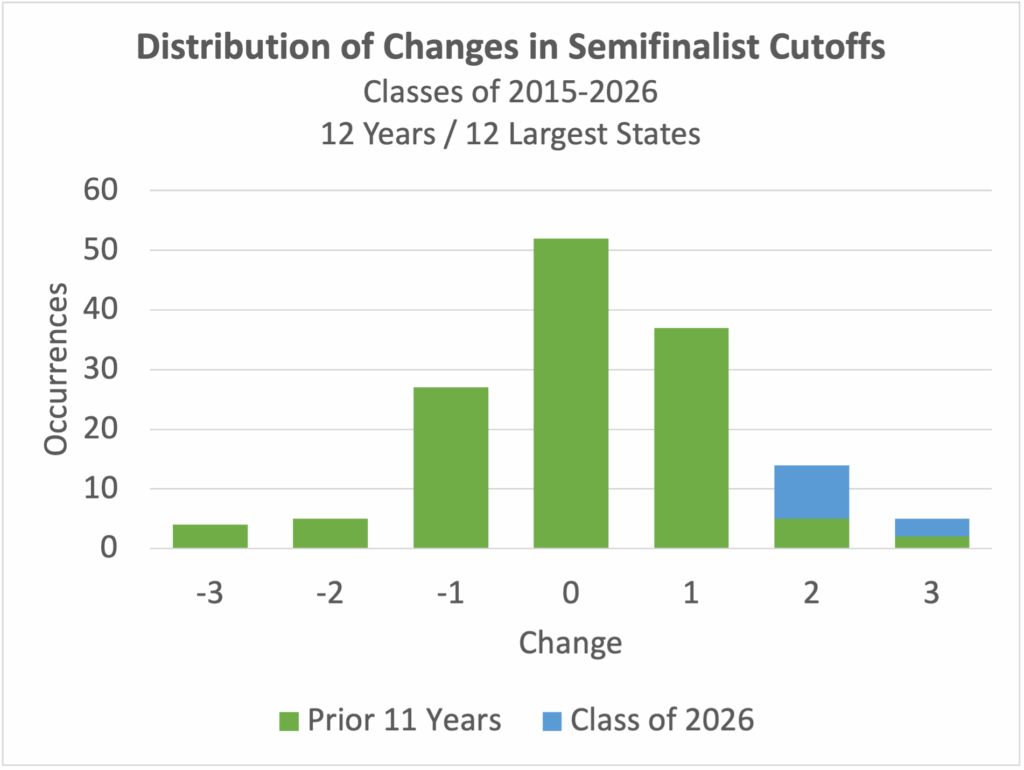

Over the last dozen years, the majority of 2- and 3-point changes in large states’ cutoffs occurred just this year.

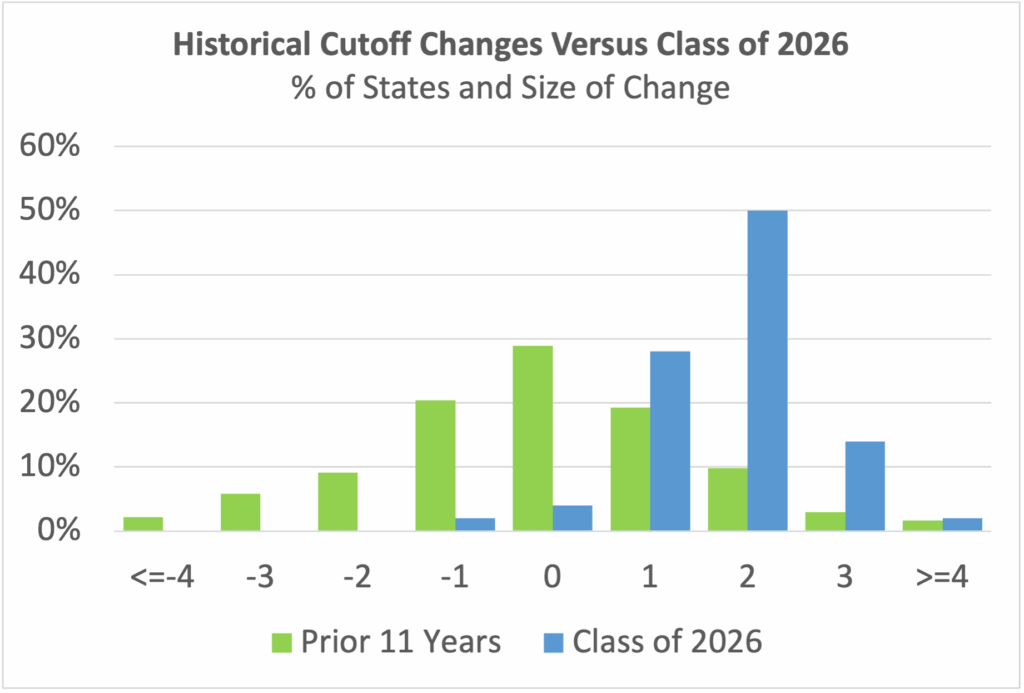

The bias is also seen when looking at all 50 states. The chart below shows how changes in the prior 11 years compare to the Class of 2026’s shifts. Historically, cutoffs remain unchanged approximately 30% of the time, and go up by 2 or more points only 15% of the time. This year, two-thirds of states saw increases of 2 or more points.

Was the PSAT fair? Was it wind-assisted?

In running events such as the 100m-dash, results do not qualify as world records if there is too much wind. The race results still stand; the gold, silver, and bronze medalists still finished first, second, and third. But the runners’ performances are not comparable to other races if they had a 15-mile per hour wind at their backs. While the October 2024 PSAT was likely wind-assisted, it was largely fair to those taking the test. The higher National Merit cutoffs did not alter the number of Commended Students or Semifinalists. Students were still ranked 1, 2, 3, etc.

Why the qualifier of “largely fair”?

On the digital PSAT, not all students answer the same questions. There is a pool of potential items. Nor is scaling done by a simple tally of right/wrong answers. As with the digital SAT, a specialized form of scoring called 3-parameter Item Response Theory (IRT) is used on the PSAT. IRT is a form of pattern scoring, where a student’s score is determined by which specific questions are answered correctly or incorrectly. If the parameters for questions were inaccurate and those questions only went to certain students, then the bias in scores may not have been uniform. A swirling wind could have helped some students and not others. The consistency of the upward bias, though, indicates that most students were boosted last October.

Scores provide needed insight

In the old world of paper PSATs, College Board shared select test forms with students, provided educators with performance data for questions, and released scales. None of that takes place with the digital PSAT. No items are released. No scoring parameters are provided. No performance data is shared. Students are not even told how many questions they got right or wrong. In short, visibility over the exam is available only by analyzing reported scores.

Those reported scores clearly show the upward bias. The number of students earning a 700-760 score on Reading & Writing increased from 62,000 to well over 74,000 (a 20% increase). The number of Math scores in that range went from 59,000 to approximately 78,000 (up more than 30%).

The changes at the very top were likely even more extreme. With the 223 cutoff seen in New Jersey for the Class of 2025, there were 12 score combinations that qualified a student for Semifinalist: 740RW / 750M, 740RW / 760M, etc. For the state’s 225 cutoff this year, there were only 6 combinations. It’s possible that the number of 750-760 scores went up by 50% or more.

So, the October 2024 test was easier than normal?

If easier is defined as more students able to achieve top marks, then the answer is “yes.” That doesn’t mean that the questions themselves were easier. The test’s scale is meant to adjust for differences. Somewhere along the line, things broke down.

Over the last two decades, the PSATs from 2011 (Class of 2013), 2016 (Class of 2018), 2019 (Class of 2021), and 2024 (Class of 2026) stand out as problematic. In those years, almost every state saw a change in cutoffs, and the direction and size of the change point to non-parallel forms (wind!). (The Class of 2014 also saw significant changes, but those were more of a bounce-back from the previous year.) The anomalous 2019 results could be traced back to a particularly mis-scaled form, which I wrote about at the time.

Implications for the SAT

The PSAT offers a snapshot of an entire class at a specific moment. In contrast, the SAT is administered on various dates and times, yet all results are reported as interchangeable. Some SAT takers may have wind at their backs, and some may be running directly into the wind. College Board’s goal is to prevent differing conditions or factor them out of the equation. Its objective is to ensure that the questions on each exam are nearly identical in content and difficulty (known as “parallel forms”), with any minor discrepancies accounted for through equating and scaling. However, PSAT results highlight the challenge of achieving this goal. Ultimately, some SAT administrations are going to yield higher or lower scores, just as observed with the PSAT.

Why aren’t you analyzing those SAT changes?

SAT data provided by College Board tend to obscure non-parallel results. Scores from individual test dates are not publicly shared. Even in the locked-down educator portals, scores are only reported in broad ranges. By the time College Board presents the results for a group of graduated students, the impact of non-parallel forms has been smoothed away, and College Board prefers it that way. If you can’t see scoring irregularities, did they really happen? The useful thing about the PSAT is that we can see them. National Merit cutoffs are far more granular than the 1400-1600 range that College Board reports annually for the SAT.

Non-parallel forms, norms, and student behavior

If test forms are not consistently parallel, then students have added incentive to repeat the SAT. As a test taker, why wouldn’t I want to stumble across an exam with an upward bias? The incentive is increased by the fact that superscoring locks in any upward bias and any positive error (see below) on each section of the test. Over time, the number of test dates taken by students applying to competitive colleges has increased, and testing calendars have shifted forward to allow for this. This may not be desired behavior, but it is rational behavior.

Due to upward shifts in SAT scores, traditional normative data like percentiles are insufficient for accurately measuring performance. PSAT students in the class of 2026 saw how tricky it can be comparing one’s performance to historical norms. The same problem arises on the SAT. Percentiles are provided for the three preceding class years. If there is an upward shift, it will not be fully reflected for more than three years. Unlike the ACT, College Board stopped reporting the number of students achieving each score nearly a decade ago and has never disclosed the impact of superscoring on score distribution. When assessing where an SAT score really ranks, students are not given the full picture.

In effect, College Board provides outdated track season averages for the SAT and expects them to be good enough to assess individual race results. Wind be darned.

Haven’t scores always been volatile?

Fluctuations at the individual level are different than those at the population level, although both can contribute to scoring uncertainty for students.

All tests contain inherent imprecision, known as the standard error of measurement (SEM) in psychometrics. SEM reflects that a single test can not accurately pin down a student’s “true score.” For this reason, College Board provides students with a score range, typically plus or minus 30 points, beneath their reported test scores.

Changes in the National Merit cutoffs can not be explained by SEM. Error in measurement is effectively random, and negative error and positive error cancel out when viewed over a large population. It doesn’t get much larger than the 1.5 million juniors who took the PSAT. SEM would not push scores upward.

The confidence intervals provided on student scores, however, assume parallel forms. Non-parallel forms are the likely cause of the increases on the October 2024 PSAT.

Instead of random error, scores were biased upwards, at least at the highest levels. There is strong circumstantial evidence that the October 2024 PSAT was not parallel to the October 2023 PSAT. In other words, students saw volatility (College Board’s inability to equate each test to produce equivalent scores) layered on top of typical volatility (the fluctuation of individual student scores due to SEM). The same problem arises with the SAT, it is simply hidden from view.

Fluke, shift, or trend

Was the observed bias on the PSAT a fluke, shift, or trend? The change in score distribution could be attributable to something unique to the October 2024 PSAT. We saw this happen with the paper tests in the past. There were outlier years that we might consider “flukes.”

Alternatively, we could be seeing a permanent shift upward in scores. Instead of wind at the back, are we perhaps seeing a move to a new track surface that will permanently raise scores? Equating a new test format is difficult. Equating a new format that accounts for future student behavior is even harder. Is it simply coincidence that scores jumped in both 2016 and 2024, the years after the introduction of new PSAT designs? It’s difficult to disprove a shift at its very outset.

Could the change reflect even more than a shift? Could it be a trend that will push scores higher still? This seems like the least likely possibility. Previous examples of major score differences have fallen into the fluke or shift buckets.

Other theories about the change

There are other theories as to why PSAT scores increased. For example, is the increase in PSAT scores due to better preparation? It is unlikely. I have spent much of my professional life helping students improve their test scores, so it may seem odd that I discount learning improvements or test preparation as an explanation. Practice and preparation do raise scores at the individual level. The behavior of a testing population, however, rarely changes quickly or uniformly.

The cutoffs in the largest 12 states went up either 2 points or 3 points. We should not have seen that uniformity if preparation and technique were the primary causes.

It’s Desmos’ fault

Probably not. Desmos, the powerful online calculator available for the PSAT and SAT, was available in 2023, as well. Students may have become more adept with Desmos, but that doesn’t explain why we also saw an increase in Reading & Writing scores. Further, a Desmos-linked impact should be less prominent at the highest score levels, since students capable of scoring 740-760 are less likely to see the benefit versus those scoring, say, 650-700.

Are the cutoffs explainable by a change in testing population?

The number of students taking the PSAT can change from year-to-year. The score level of those students can also change. For example, if a state begins requiring all students to take the PSAT, the average score will go down, while the number of high scorers may move up (in previous years, we saw this in Illinois and Michigan). This is a poor fit for what we saw with the PSAT. Scores went up across virtually all states. There is strong evidence that there were forces that pushed Selection Indexes up by 2 points.

Is the change attributable to the adaptive nature of the exam?

The RW and Math PSAT each have two stages. A student receives an initial set of questions. Based on their performance on that first stage, the student receives a set of easier or harder problems in stage 2. An adaptive test can more quickly narrow down a student’s score, but there is always the chance of what is known as routing error. In other words, a student with an ultimate score of 640 probably should have been routed to the harder stage 2 problems rather than the easier ones. There may be less accuracy had the student been routed to the easier set of questions. However, routing error should be neutral for the population as a whole. Further, College Board research maintains that routing error has a minimal impact on scores. Most important, students scoring at the National Merit range would have been routed to the harder stage 2 with 99+% certainty.

IRT scoring may have been a factor. Item parameters are calculated beforehand through pre-testing, where the question is included as an unscored item on earlier exams. Inaccurate parameters can lead to inaccurate scores.

The digital PSAT and SAT are shorter than their paper ancestors, and this can contribute to score instability. An individual problem or two plays a greater role on a shorter exam. While this can be offset by the adaptive nature of the test, longer is always better when it comes to test reliability. The PSAT tries to place students on a 160 to 760 scale with only 40 scored Math questions and only 50 RW questions.

Could NMSC have changed how it calculates cutoffs?

Each year, some students are unable to take the PSAT because of illness or other extenuating circumstances. These students can apply to enter the scholarship program via Alternate Entry using an SAT score. The deadline for application is generally April 1 after the PSAT, although students can use SAT scores through the June test date. In the past, NMSC has only used PSAT scores to calculate cutoffs (with an exception made during the COVID-related cancellations in 2020). Because students can take the SAT on multiple dates, their scores skew higher than PSAT scores. If NMSC were to include them in the cutoff calculations, it would likely lead to cutoff inflation. Compass has not heard that any changes were made for the Class of 2026.

Did Compass see the changes coming?

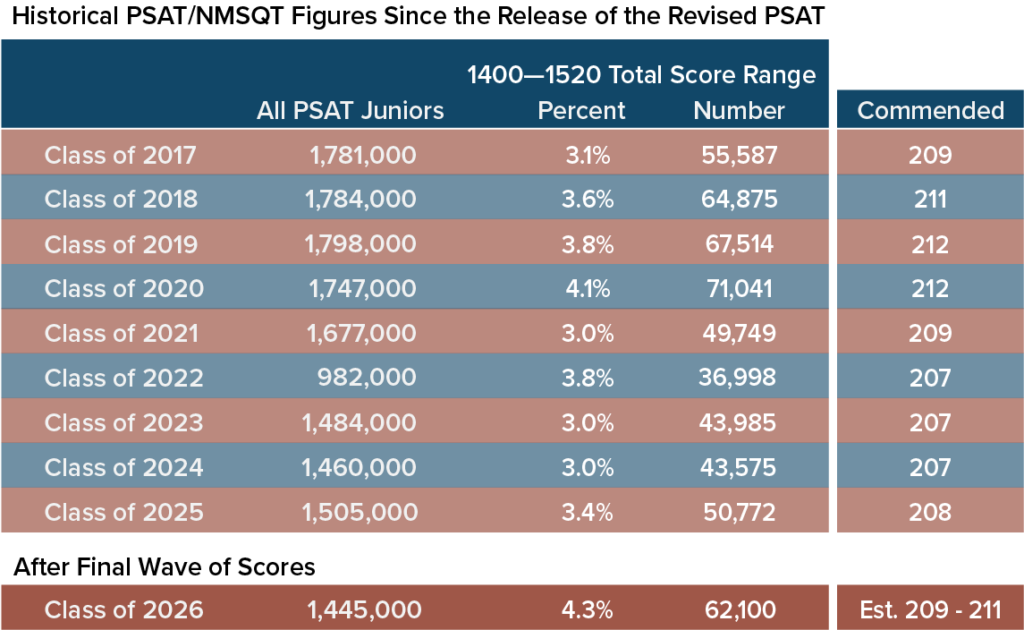

Only in part. Once PSAT scores were available in November, we noted the uptick in 1400-1520 scores and projected that the Commended cutoff would move up 2 points to 210. While upward movement was expected nationally, we did not foresee the breadth of the changes. The table below shows that there were far more high scores in the Class of 2020. The class also saw a higher Commended of 212. Yet the highest Semifinalist cutoff only reached 223. Cutoffs as high as 225 were without any precedent.

What about expectations for the Class of 2027 and beyond?

More than ever, PSAT students have to be aware that “past performance is no guarantee of future results.” In November, Compass will report on the scoring of the October 2025 exam and provide our range projections. We won’t know what future cutoffs will be, but the PSAT scores may provide clues on the question of fluke, shift, or trend.

Why does each state have its own Semifinalist cutoff if the program is NATIONAL Merit?

This is always a hot button question. NMSC allocates the approximately 17,000 Semifinalists among states based on the number of high school graduates. That way, students across the nation are represented. It also means that there are very different qualifying standards from state to state. A Massachusetts student with a 220 might miss out on being a Semifinalist. If she lived 10 miles away in New Hampshire, she would qualify.

NMSC sets a target number of Semifinalists for a state. For example, California sees about 2,000 Semifinalists every year, Michigan 500, and Wyoming 25. In each state, NMSC determines the Selection Index that comes closest to matching its target number of Semifinalists. If 1,900 California students score 222 and higher and 2,050 score 221 or higher, then the Semifinalist cutoff would be 221 (this assumes that the target is exactly 2,000). Because score levels can get crowded, it is easy for cutoffs to move up or down a point even when there is minimal change in testing behavior or performance.

No Semifinalist cutoff can be lower than the national Commended level. Cutoffs for the District of Columbia and for U.S. students studying abroad are set at the highest state cutoff (typically New Jersey). The cutoff for students in U.S. territories and possessions falls at the Commended level each year. Boarding schools are grouped by region. The cutoff for a given region is the highest state cutoff within the region.

When are National Merit Semifinalists announced for the next class?

The Commended cutoff will become unofficially known by the end of April 2026. The lists of Semifinalists will not be distributed to high schools until the end of August 2026. With the exception of homeschoolers, students do not receive direct notification. NMSC asks that schools not share the results publicly until the end of the press embargo in mid-September, but schools are allowed to notify students privately before that date. NMSC does not send Commended Student letters to high schools until mid-September. Compass will keep students updated on developments as the dates approach.

Do state and national percentiles indicate whether a student will be a National Merit Semifinalist?

No! Approximately 1% of test takers qualify as Semifinalists each year, so it is tempting to view a 99th percentile score as indicating a high enough score — especially now that College Board provides students with percentiles by state. There are any number of flaws that rule out using percentiles as a quick way of determining National Merit status.

- Percentiles are based on section scores or total score, not Selection Index

- Percentiles are rounded. There is a large difference, from a National Merit perspective, between the top 0.51% and the top 1.49%

- Percentiles reveal the percentage of students at or below a certain score, but the “at” part is important when NMSC is determining cutoffs.

- The number of Semifinalists is based on the number of high school graduates in a state, not the number of PSAT takers. Percentiles are based on PSAT takers. States have widely varying participation rates.

- Most definitive of all: Percentiles do not reflect the current year’s scores! They are based on the prior 3 years’ performance. They are set even before the test is given. And if you are going to use prior history, why not use the record of prior National Merit cutoffs rather than the highly suspect percentiles?

Entry requirements for National Merit versus qualifying for National Merit.

Your PSAT/NMSQT score report tells you whether you meet the eligibility requirements for the NMSP. In general, juniors taking the October PSAT are eligible. If you have an asterisk next to your Selection Index, it means that your answers to the entrance questions have made you ineligible. Your answers are conveniently noted on your score report. If you think there is an error, you will also find instructions on how to contact NMSC. Meeting the eligibility requirements simply means that your score will be considered. Approximately 1.4 million students enter the competition each year. Only about 55,000 students will be named as Commended Students, Semifinalists, Finalists, or Scholars. See National Merit Explained for more information.

Art,

Appreciate all you do, and your patience answering what seem like very similar questions. My daughter is in Georgia and received a 219. I’ve been following your article above and see with the newest scores, the projected threshold moved from 218->219. I know your range goes up to 220. How likely is it that we’ll see 220 or higher? Thanks.

Matt,

Yes, once I had the second wave of scores available, it became clear that this year was more likely to be an “up” year than a “down” year. How high is up? I don’t know that on the state level. I still think 219 is the “most likely,” but 220 is a real possibility (Georgia hit it in 3 of the last 9 years, but 2 of those years had more 1400-1520 scorers than we are likely to see this year). 218 also has a shot. So 220 or higher? I think 35-40% is a fair estimate.

Art,

Thank you for the well thought out, and rapid response! Matt

Hello my daughter is in junior year and got perfect psat score of 1520. Will this guarantee semifinalist? She also took SAT and scored 1540. Is that high enough score to become finalist?

Mary,

Congratulations to your daughter on her fabulous scores! Yes, she will be a Semifinalist. And, yes, her 1540 is high enough as a confirming score. She still needs to meet the other requirements to be named a Finalist: recommendation, grades, and essay. But that’s something to think about next September. For now, she has everything she needs.

Hello,

In the state of Minnesota, they haven’t crossed 218 as a cutoff for the past few years. However, with everyone saying scores are going in an upward trend, what is the chance a student gets Semifinalist status as a student in MN with 218 as their NMSC score?

Thanks

Arnav,

You’ve described the dilemma in a nutshell. Recency points to a 218 qualifying. The super-competitive years from 2017-2020 point towards another possibility. Nationally, I don’t think the scores are going to be as extreme as we saw in the classes of 2019/2020, but they are still going to be competitive. I’d put the odds around 50/50. Unfortunately, a 218 is dead center of the “fingers-crossed-until-September” zone.

Hi,

If you had to put a number on your chance of seeing the cutoff for Texas remain at 219 rather than the jump to 220 as you have predicted, what would it be?

Any chance of seeing a 218?

Also how historically accurate have your predictions been?

I’m nervous because I got a 219 in Texas 😅

Thanks!

John

John,

Let me address the accuracy question, because it is an important one. How accurate are my predictions? Not very. And that’s about the best that can be expected. Texas is a great example of what I mean. Realistically, there are 4 potential cutoffs: 218, 219, 220, and 221. We haven’t seen a 218 in more than a dozen years, and the scores this year are strong nationally. So there is a low chance of that happening (we’ll call it 3%). In a normal year, what’s the most common cutoff? The previous year’s cutoff, which occurs about 1/3 of the time (more than that in a large state such as Texas). We’re seeing scores that would have me rank this year as “above normal,” so let’s call the odds of a 219 25%. In the classes of 2018 – 2020, Texas’ cutoff was 221. What did those classes have in common? High numbers of 1400-1520 scorers. But we aren’t likely to see 70,000 of them this year. So I don’t consider 221 my favorite. Let’s call the odds 35%. And we need to reserve a 1% chance of the cutoff going to 222. That would leave 220 at a 41% chance. [And as with any oddsmaker, I consider it within my rights to change my odds at any time!] That would make the 220 “most likely,” and yet it’s going to be right only 2 times out of 5.

The odds of being right in New Jersey are higher. The odds of being right in Alaska are lower.

This is all a long way of saying that I hope my information is hopeful, but I also hope that you make exactly zero life decisions on it. Stay positive, find useful things to do between now and September, and let’s both hope that I am wrong!

Hi Art, Thanks for this amazing resource! Truly enjoyed the article and the clarity with which its written. My son got a 1470 in OR with an index of 218. Your highly likely cutoff for OR is 217 but the range is 215-220. What do you think? Will he make the cutoff for OR?

Harry,

Oregon is one of those no one knows nothin’, sort of states. The only other state that has been as high as 221 and then back down to 216 is Colorado. I could see Oregon at 217 and, unfortunately, I could see it back around 220. Your son’s 218 probably puts his odds at just over 50%.

Hi Art, Thank you for all you do. This is an amazing resource. Could you please expand on your comment that Oregon is a no one knows nothin’ sort of state?

My daughter has a selection index or 220. I know Oregon has reached 220 a couple of times and 221 once in 2019. What’s the likelihood of it going from 216 in 2025 to 221 for 2026? It’s nerve-wracking because Oregon department of Education moved from PSAT to PreACT which will probably skew the SI in unpredictable ways.

Thank you again!

Betty,

I was just referencing how unusual it is for a state that has hit 221 to also hit 216. But your comment forced me to learn somethin’ rather than nothin’.

Thank you for pointing out the DOE change. I had missed that, and it is likely to make a difference. What we normally see in these situations are lower participation rates and lower scores. If I have it right, Oregon pays for all sophomores to test, and it switched in the fall of 2023 to PreACT. That impacts junior-year testing in multiple ways. In many districts, junior PSAT-testing was linked to sophomore testing. Districts either paid for juniors or gave them a subsidized rate. Now, some districts are telling juniors that they are on their own. And finding an out-of-district seat for the PSAT is not easy. The other impact is that the class of 2026, for the most part, didn’t have the practice experience of the sophomore PSAT.

Let’s look at some numbers. I don’t know how many juniors took the PSAT this fall, but it was already on a downward trajectory. I expect it to hit a new low this year. College Board didn’t provide score breakdowns for the class of 2019 — the class that saw the 221 cutoff — but it did for the class of 2020 (a 220 cutoff). There were 15,616 test takers and 4% scored in the 1400-1520 range. By the class of 2024, that had dropped to 11,295 and 3% (I wish those percentages weren’t rounded). Last year, class of 2025, there were only 8,876 juniors with 4% scoring in the top range. Sophomore participation had plummeted to 3,278. So we could very well see half the number of juniors in the class of 2026 as those 15,616 just 6 years ago. It could even drop more than that.

This all makes me skeptical of Oregon seeing a large jump. If I take the other side of the argument, I’d point out that students in NMSF range will try harder than most to take the PSAT. And there is the wildcard of Alternate Entry. I don’t find those arguments that compelling. Based on all of the above, I don’t see Oregon going back to the days of 221 cutoffs. I’m even a bit skeptical of it getting back to 219/220. It sure looks to me like your daughter will be a Semifinalist.

And this is why I love comments. They help me learn new things. Thank you!

So Art are you saying Oregon cutoff for Semifinal might end up being the 216 like the last few years or will it still jump to 217 as you originally expect?

Harry,

All I can say is that the situation is more fluid than I expected. Honestly, had I not known about the recent changes, I probably would have had my “most likely” at 218. It definitely means that a flat cutoff (216) has a better shot than in most states.

Hello. I’m a teacher and tutor in New York State. I have a student that just got a PSAT score of 1500 (740 V, 760 M) with a selection index of 224. I don’t think NY has ever had a selection index above 221. Even with the shift upwards in scoring this year, it’s pretty likely he’ll make the Semifinalist cutoff this year, right? I mean, New York would have to jump five points from its 220 last year to a 225 for him to not make the cutoff. That seems unlikely to me, but what do you think?

Greg,

Yes, it’s well beyond unlikely. There is absolutely no way that New York goes to 225. Your student will be a Semifinalist. Congratulations to him!

Hi I have just gotten a 222 index score – 1490 PSAT in Washington State and this means a lot to me so I was wondering the chances I would qualify for the National Merit Semifinalist as I am really hoping on it not being a 223 after all the work I put in.

Thanks a lot Mr. Sawyer

Sam,

As you probably already know, Washington has never had a 223 cutoff. While the national scores this year look to be higher than they’ve been the last few years, I think the possibility of Washington moving to 223 is very low. I wish I could rule it out entirely, but odd things can happen at the state level, and I don’t want to mislead you. I’d put your chances at 95%.

Hi,

I scrolled through and didn’t see any questions about WV. My son’s selection index is 214. I can see that the cutoff has never been that high in our state, but I was still hoping you could ease a nervous mom’s nerves. I know that scores are looking really good this year!

Thank you! Your knowledge of these statistics is amazing!

Annie,

WV almost always has a Semifinalist cutoff at the Commended level (no state can have a cutoff below the Commended level). We saw the very unusual occurrence last year of the West Virginia cutoff being above the Commended cutoff. But it was 1 point above! I don’t see any reasonable combination of events that would lead to a 215 cutoff. Commended is likely in the vicinity of 210/211. Scores are looking good, but they are still off from the years where we saw a 212 Commended. Even at 2 points above the Commended range, your son qualifies comfortably. He will be named a Semifinalist in September. Congratulations!

My son (a junior) didn’t score high enough to be commended, yet it says he scored high enough to be eligible for the NMS. He is only in the 97th percentile. Am I missing something?

Heather,

If you look at page 2 of your son’s score report, there should be a box labeled Eligibility Information. That presumably says that he meets the entry requirements and will be considered. That same information is on every U.S. junior’s report. It is a confusing way of describing things. College Board doesn’t actually know what the cutoffs will be, so there would be no way for it to indicate a score that is high enough.

Percentiles can be misleading. If his Selection Index is 208 or higher, then I think he at least has a chance of being Commended. It’s more likely, though, that we’ll see a Commended cutoff at 210 or 211.

Hi Art,

Thank you for all you do! How do you feel about a score of 222 in California?

Tina,

I think it has a very high chance of qualifying. Yes, California went as high as 223 in the class of 2023, but that was a more competitive year than even this “up” year. California testing has also declined from its peak. I think we are more likely to see a 221 or 222. I’d put your chances at about 95%.

Why is the ERW score weighted *double* the Math score in the Selection Index? It effectively gives ERW-strong students an advantage over Math-strong students, and I haven’t seen any reasonable explanation for it.

Dave,

I don’t know that there is a reasonable explanation of it, but I know a bit about the history (which is often misinterpreted). The weighting is not new. In fact, I believe it goes back to when the NMSC joined forces with College Board to merger their exams into the PSAT/NMSQT. I don’t have definitive proof of the following, but here is my theory. The original NMSQT had 5 components: English Usage, Mathematics Usage, Social Studies Reading, Natural Sciences Reading, and Word Usage. In other words, it already put a limited weight on math. The PSAT, at the time, had Verbal and Math scores. The verbal exam had antonyms, analogies, sentence completions, and reading passages. So NMSC presumably felt that a doubling of the Verbal score made the most sense in keeping some comparability to the previous exam. In other words, this formulation is more than 50 years old.

It has gone through some changes, though, and that’s where some of the confusion comes in. In the 1990’s College Board was sued by the ACLU and the National Center for Fair Testing because of skewed proportion of male Semifinalists and scholarship winners. Part of the settlement was the inclusion of a Writing section on the PSAT, because female students outperformed males students on that test. The Writing section was essentially derived from the Test of Standard Written English, which had been administered — but scored separately from — the SAT (it had been dropped from the SAT several years earlier and, with some mutations, became the SAT II: Writing test). So now the PSAT diverged a bit from the SAT and had a Verbal, Math, and Writing section. Those three scores were added to get the Selection Index. The the top SI remained at 240. Crucially, though, this change was not the root of the doubling of the verbal scores. That pre-dated the addition of Writing.

This structure eventually became adopted by the SAT, and scores moved from 400-1600 to 600-2400. So during that period, it wasn’t a doubling of the verbal score so much as adding up all of the components of a test that just happened to have a Reading section and a Writing section.

In 2015, though, the PSAT and SAT switched back to a 400-1600 scale and Reading and Writing were partially merged. I say partially, because although they combined to give the PSAT’s 160-760 ERW score, they each had their own 8-38 test scores, as did Math. So the SI at that time added up all of the test scores and doubled them. The top score was now 228. The digital PSAT, introduced last year, has added a new twist. There are no longer separate Reading and Writing sections or scores. NMSC, however, decided to preserve the weighting of the verbal score (after all, it had been doing so for 5 decades).

That is much more than you probably wanted, and also doesn’t fit what you might consider a reasonable explanation. But once I decided to go down the rabbit hole, I decided to go all in.

Thanks for the explanation. I am curious what the male to female distribution of semifinalists has been since the change in scoring following the ACLU settlement. I have not found that information readily available online. I ask because my son’s high school which is newer, has had 5 semifinalists who all advanced to finalist, all female, and 1 commended student, male. since the fist Junior class in 2018. On the face of it, it appears that the formula might have over compensated, but it could just be coincidence. That said, my son did score a 220 index this year ( in NC) so hopefully he will buck the trend.

Linda,

I’m pretty confident that the situation at your son’s school was a coincidence (or just confirmation that it has done a great job at attracting excellent female students). The addition of Writing was not an overcompensation. NMSC avoids breaking down numbers by M/F — lawsuits will do that. I’ve seen some attempts to get at the data via the names of Semifinalists. I’ve tried to avoid going down that pseudo-science rabbit hole. The best confirmation comes from the data that College Board used to release. Back in 2015 (almost two decades after the PSAT change) it released the number of male and female students at every SAT score, and it did so for combined M+R and M+R+W. If we look at the top 16,000 students (that’s not how the state-by-state numbers are calculated, but you get the idea), the split was 61%/39% for Math+Reading and 56%/44% M+R+W.

As for the part that you are probably more interested in (!), I think it is very unlikely that North Carolina will hit a new record this year. I really like his chances at 220.

Thank you for the detailed response! As you said, it’s not what I would consider a reasonable explanation, but it does provide some historical context.

I live in Wisconsin and my Selection Index is 213. Is it very unlikely that I will be a semifinalist?

Julia,

I’d at least remove the “very.” Wisconsin’s cutoff has been at 213 in 3 of the last 5 years. What makes me think it is less likely this year is that we are seeing strong scores nationally, and in that type of year, Wisconsin’s cutoff has gone as high as 217. I think a 214 or 215 is most likely, but I’d put the odds of a 213 at about 20-25%.

Your article and statistics are so fascinating, thanks! How confident do you feel about your Virginia prediction? My child is at the top of your estimated range with a 223, which I am really proud of, but I keep hearing from them that “so many people got really high scores” this year. Maybe this is just because of their school, which is very competitive, but I also see your discussion tha scores are way up overall. I know there is no way of knowing for sure, i am just trying my best to manage expectations in our house!

K,

Every year — even in down ones — I hear the same thing from students about “so many people…”. It’s tough to stay level when it feels like everyone did so well (hint: the students with the highest scores talk and get talked about the most). And lots of students did do well. But it is hardly record numbers. I am just crunching the final wave now, and we’ll end up with about 62,000 scores in the 1400-1520 range. That’s still well below the 2018 – 2020 figures. I don’t think Virginia will even go to 223 (which would be a record). I certainly see no precedent for it going to 224. Maybe it’s not 100% guaranteed, but a 223 feels 99.5%.

And I should have mentioned that your child is among those who did really well!

Thanks, we are very proud! We will keep our fingers crossed that they get good news in the fall.

Ok, Art… after the final wave of scores came in. I see you’re still holding strong to 220 in Texas. Daughter scored a 1480 760Math and 720 Reading. 220 index. Give me your odds on staying at 220 or below. I’m reading that we may not see 2018-2020 index scores so that keeps me hopeful! I read your prior reply about not being very accurate. (Ha!) do you tend to predict lower or higher? Just trying to see our odds here.

Heather,

Yes, I’d say that the last batch of scores was good news. The total numbers of test takers is down from last year and the percentage of high scores was lower in the last batch (as expected, but nice to have confirmed). There is always the danger, of course, of reading too much into the national numbers. The decline may have been focused outside of Texas, for example. I’d peg the chances of a 220 qualifying as 2 out of 3 at this point. 221 is still lurking. If I’m choosing a Most Likely between two well-matched candidates, I’ll usually stick with the one closer to the prior year’s cutoff. I’ve been looking for an excuse to make a Latin pun: Natmerit non facit saltus. Which is kind of true for larger states.

Hello, checking back in again! My daughter got a 212 index score in Oklahoma, and we were wondering about your thoughts on her chances on making it and if your predictions for Oklahoma have been accurate these past couple years.

Layla,

The final batch of numbers confirms that, nationally, it’s a modest up year. I don’t think we’re going to see Oklahoma at 216, for example, but I’m more convinced that we won’t see a lot of state cutoffs dropping either. I still have 212 as my Most Likely, but I’d probably rank it as 50% chance of 212 or lower and 50% chance of 213 or higher. Trying to predict state results can make one look foolish. If we look at the last 3 years, for example, why was Oklahoma at 211 in two of them and 208 in the other? There wasn’t an indication in the national numbers that would indicate that level of change.

What about a 216 in Florida? Is it very unlikely that I will be a semifinalist?

Tina,

The national numbers are showing scores moving up this year. For a 216 to qualify, Florida would need to move against the tide. Much stranger things have happened. I’d put the chances at about 10-15%.

Hi,

My daughter and I are in Texas and she got a 220 index score. She is aiming to become a National Merit Finalist but she is worried that her score isn’t high enough to get semi-finalist. Now that all the scores have released, what would you say her odds are to become a semi-finalist? Thanks.

Marie,

I think the chances of a 220 qualify are about 2 out of 3. I still don’t think we can rule out a 221. I’m afraid that that may not be the level of reassurance that your daughter would like, but she is still in an excellent position to become a Semifinalist.

Thank you so much for replying! Just wondering, would you say the final wave was for the better or worse?

Anything that kept us away from the extremes was better. The final wave did just that.

Thank you so much for your help! My daughter is still a little worried but knowing she still has a fighting chance helped her calm down a little. One last question, will there be any more updates in the predictions or is it just a waiting game now? Thanks again!

Marie,

In April or May we should get leaked word of the Commended level. In theory, that could spark some revisions. In practice, they will likely be minimal, since I doubt that we are in for much of a surprise. For the most part, it’s all about waiting.

Hi,

When you say the number of scores ranging in the 1400-1520 range is high, do you know how many are in the 1400-1449 range vs. 1450-1520? Wouldn’t having more students score in the higher range impact state cutoff scores? Conversely, if a lot of the scores are in the low 1400’s, wouldn’t that make a difference in cutoff scores as well?

Cheryl,

There was nothing in the last set of scores that made me reevaluate my estimates for New York. I still think 220 is the most likely cutoff, and I still believe that we cannot rule out 219 or 221.

College Board doesn’t release any data beyond the 1400-1520 set. You may be referencing my post where I was describing the general distribution of scores. There are always going to be more modestly high scores than very high scores — it’s just the way the distribution falls. I don’t have any insight into changes for this year in those figures.

Hi,

We live in Ohio. My son is in his Junior year and got a 214 index score on PSAT. Is there any chance of getting into the Semifinalists category for 2026?

Thanks.

DeepaRajan,

I think it is likely that your son will be named a Commended Student. While there may be some Semifinalist cutoffs that decline this year, I doubt that we will see any new record lows. Ohio’s cutoff has ranged between 215 and 219 over the last decade.

Hi Art, After the final wave, I see you bumped Florida to 220 for the upper limit. What do you think the chances are that it will, as predicted, be 218 (my daughter’s score)? Also, if she is borderline, is there any way to determine this definitively before next August/September? Thank you!!

CMM,

The easy part first: short of Wikileaks suddenly taking interest in National Merit scores, there is no way to determine anything definitively before next Aug/Sept. The only thing that we are likely to know in April or May is the Commended level. That won’t give us enough information to say anything about Florida.

In doing my final pass, I took a hard look at my ranges. Essentially, I asked myself, “If you think the Most Likely is 218, do you feel comfortable saying that the cutoff can not reach 220?” I decided that I wasn’t comfortable. I wouldn’t read too much into that. I’d peg 218 or lower as 70% likely. I wouldn’t argue with someone who said that it is even more likely.

I see you bumped up the Mississippi range to include 215 and the most likely to 213. My daughter has a 214 which makes me nervous. Can you give me a % chance she qualifies? Looking through your historical data I never saw a year Mississippi jumped more than 2 points so hopefully that holds true this year as well. Thanks for all you do.

Hector,

While I felt like I couldn’t exclude 215 in my estimated range, I didn’t really change my take on Mississippi. 213 remains my most likely and I’d even say that 212 is more likely than 214. When looking at score changes, I think about drops as well as increases, since either direction indicates variability. MS has twice seen drops of 3 points. This is to be expected. Because of a relatively low PSAT participation rate, MS is one of the smallest states in terms of NMSP entrants. I think a 214 is in the 90-95% range.

Thanks for pulling all of this information together. It’s so helpful! My son is in PA and is right at the projected cutoff of 219. I know you are projecting an overall increase in state cutoffs, but kept PA at 219 (same as the past two years). How confident are you in the 219 and should he be worried about it going up to 220 this year. Thanks again!!

Greg,

I like to point out to students that it is much more productive to worry about things that you can control. Is you homework done? Are your gutters clean? Are you ready for the SAT? I think the same thing applies to parents (especially that second one). There is really little information that lets us distinguish between a 219 or 220. I parse things a number of different ways, and I never alighted on one that made me think 220 was the *most* likely result. For example. when I looked at PA’s cutoff over the years where the Commended level fell between 208 and 212, the average was 218.8. We’ve seen PA’s cutoff at 220, but it was in years where we saw far more upward pressure on cutoffs across the country. I’m optimistic about a 219, I just don’t think we can say it is a guarantee. 80%?

Hi Art, Thanks so much for all this information! It’s been so great and also the quick updates after the scores are announced are amazing. I see you moved Florida from 216-219, to 216-220. My daughter has a 218 so I guess we’ll just have to wait and see what happens. Florida has hovered around 216/217 it looks like and was 217 last year. Have you seen 2 point jumps very often? Wondering why you increased the upper end from 219 to 220 based on this last batch of scores. Thanks so much!!!

Jessica,

For part of my reply, I’m going to quote myself from another comment I made after you submitted your question: “In doing my final pass, I took a hard look at my ranges. Essentially, I asked myself, “If you think the Most Likely is 218, do you feel comfortable saying that the cutoff can not reach 220?” I decided that I wasn’t comfortable. I wouldn’t read too much into that. I’d peg 218 or lower as 70% likely. I wouldn’t argue with someone who said that it is even more likely.”

As for 2 point jumps: In large states such as Florida, they are not common, but they do happen. I’ve tried to factor that into my odds. Best of luck to your daughter!

Hello Art,

With the last wave of scores have released, any chance NJ would increase to 224? Reading the comments about this state would be the one to go up a point makes me a bit nervous. My daughter got 1490, which gave her a 223 SI… thanks for your time.

Tricia,

There was certainly nothing that made me feel that a 224 had become more likely, but we can’t completely rule it out. Here is a mantra: “It’s never happened before. It’s never happened before. It’s…” Positive thoughts!

Is there any chance that Missouri’s cutoff goes down to 213 this year? It’s so hard to be so close!

Jade,

It is hard, and you’ll need to wait until September to know for sure. My feeling is that Missouri is likely to come in at 214 or higher, but I can point to the 213 in the class of 2023 and send you some positive vibes!