Ask a dozen people about college admission testing and you’ll get a dozen different takes.

What you hear depends on whom you ask and the relationship they have with testing. At times, testing chatter can be a dizzying web of musings, opinions, personal beliefs, and generalizations.

Ideally, a reckoning with tests should be informed, candid, individualized, and empowering. At Compass, we sit at the nexus of perspectives—those of students, parents, counselors, admissions committees, enrollment managers, coaches, and the test makers themselves—which paints a richer picture of the complicated and ever-changing testing ecosystem.

With the most popular spring test dates 3–4 months away, it’s the right time to consider the latest testing revelations that are shaping the guidance of experts and driving the decisions of students.

- The decline in testing was caused more by cancellations than by an increase in test optional policies. Expect a testing rebound as conditions improve.

- Test scores are likely to be more important for the class of 2022—and certainly for the class of 2023—than they were for the class of 2021.

- Those without scores will face increasing competition from those with scores.

- Test optional policies have made popular colleges even more attractive and competitive.

- Sending scores may imply a greater likelihood of admission. That is part cause and part correlation.

- The importance of scores may differ between Early and Regular Decision rounds.

- The importance of scores depends on where you are and where you hope to be.

- Colleges have gone test optional while students have stayed “test optimal.”

- If you’re on the fence about sending a score, you probably should send it.

- Computer-based SAT/ACT testing will be widely available in the next 1–2 years, creating another decision point for students.

The decline in testing was caused more by cancellations than by an increase in test optional policies. Expect a rebound as conditions improve.

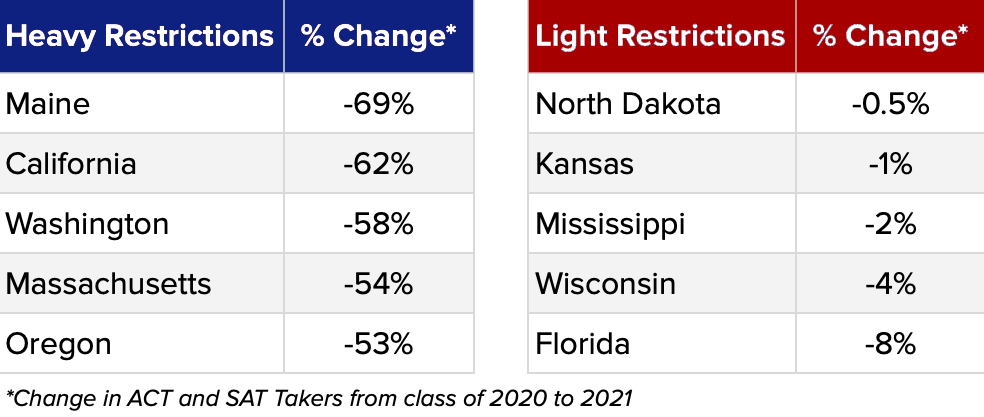

Digging into recent College Board and ACT data helps quantify and compare the factors that pushed test taking numbers lower last year. Domestic SAT and ACT takers in the class of 2021 were down 32% and 23%, respectively, from the prior class. The extreme declines occurred in states where COVID waves coincided with popular testing times or where more stringent lockdown requirements remained in place.

Differing Approaches to COVID Restrictions and the Impact on Testing:

Students in the class of 2021 had fewer opportunities to test. In many states, the class of 2021 had to navigate narrow windows of availability. And when test centers were open, they were heavily oversubscribed. The test-taker numbers agree with Compass’s research into test site cancellations. For example, we estimate that 85% of ACT locations in California were closed during the 2020–2021 school year. In Florida, by contrast, approximately 85% of the test sites were open during that period.

Students in the class of 2021 had fewer opportunities to test. In many states, the class of 2021 had to navigate narrow windows of availability. And when test centers were open, they were heavily oversubscribed. The test-taker numbers agree with Compass’s research into test site cancellations. For example, we estimate that 85% of ACT locations in California were closed during the 2020–2021 school year. In Florida, by contrast, approximately 85% of the test sites were open during that period.

One of the reasons for the steeper drop in SAT takers was the exam’s prominence in the states most impacted by closures. California alone accounted for one-quarter of the decline in total SAT takers. While the University of California eliminated the use of the ACT and SAT for admission with the class of 2021, the similar testing declines in Oregon and Washington point to COVID-related restrictions as the primary factor in the drop.

We also see evidence of COVID’s impact on test choice—or lack of it. Traditional “ACT states” had higher drops in SAT takers, and traditional “SAT states” had higher drops in ACT takers. This bucked the longer-term trend of students being able to select the exam they happen to prefer. School day testing provided one of the only testing options in many areas, so the choice was made for students in many cases. With weekend testing availability opening up for the classes of 2022 and 2023, we expect the long-term pattern of test independence to return.

College Board reported that 1.4 million students in the class of 2022 had already taken the SAT by September 2021. At the current pace, we expect SAT and ACT testing volumes to increase by 15–20%, reversing at least half of the previous year’s decline. Students in the class of 2023 are fortunate to be entering their testing window without wide-scale closures in any state, so we expect further recovery.

Test scores are likely to be more important for the class of 2022—and certainly for the class of 2023—than they were for the class of 2021.

Students, parents, and counselors typically use recent past class year data (behavior, choices, and outcomes) as guidelines to form their own plans and expectations. That approach doesn’t work as well right now because we’re in the midst of a multiyear period of chaos on both sides of the admissions market. The data is lagging and incomplete and therefore not necessarily a proxy for the next cycle and beyond. The reality is that the college admission timeline has always trailed the testing timeline; it’s just more problematic during a period of rapid change because it requires us to plan based on informed speculation rather than precedent.

Let’s view the pandemic’s impact on testing by class year (high school grad year):

Class of 2020

Testing was not impacted at all. Fall college enrollment was down and the first year of college was negatively impacted, but the testing window was unaffected.

Class of 2021

Testing was significantly impacted, but it was a fragmented class. Some of the highest achieving students secured strong scores early (by February of 11th grade) before the most popular spring dates were decimated. This led to under-testing for some and no testing for many others. Options were highly contingent on location, resources, and the timing of COVID-19 waves. Few were able to fully optimize a complete testing plan. Colleges in turn were extraordinarily accommodating and gave students the full benefit of the doubt. The lack of a test score was not a conspicuous omission. And yet, an implied edge went to those who managed to submit strong scores. This class populates the first and most current data set of widespread test optional admissions, and it will represent a short-term bottom.

Class of 2022

Testing was again significantly impacted, and it was another fragmented class, yet in slightly different ways. Unlike the preceding class, a delayed start was more common than a premature shutdown, as test site availability has almost returned to normal. Overall, testing numbers have bounced back but not evenly everywhere. And when a testing year is constrained, it leads to compromised experiences. The ability to take full advantage of superscoring, for example, was undermined by cancellations. We won’t begin to know how testing will play out in admissions until late winter/early spring.

Class of 2023

Students are advised to act based more on what can be predicted and less on what has been heard or witnessed from recent prior classes. Testing opportunities are back, and colleges know that—especially colleges that justified their temporary test optional policies on the basis of reduced opportunities to test. Each student should use a cost-benefit analysis of their own particular set of goals and circumstances. All things being equal, applicants who have scores to report will retain a potential advantage over those who sit out testing from the start. The most prudent path is to strive to obtain competitive scores. Having the option to send scores—to all colleges, to some colleges, or to no colleges—maximizes a student’s decision-making opportunity.

Those without scores will face increasing competition from those with scores.

In the class of 2021, the unavailability of testing meant fewer students scoring well. As the total number of test takers increases, the total number of high scores will climb back up, too. More than 10,000 students who would’ve had an ACT superscore of 35 or 36 were prevented from having one. They will be back, and the same is true at 34, 33, and so on.

Consider only the top ACT score of 36. Historically, the number of students scoring 36 has doubled every three years. In California, for example, the number of students with perfect scores grew by a factor of 20 between 2009 and 2020. The pandemic interrupted this streak, but top-scoring California students are resurfacing. Some will be applying to the test free UC and Cal State systems, but most will also be applying to selective test optional schools nationally where they hope their top scores will provide a boost.

Test optional policies have made popular colleges even more attractive and competitive.

Plenty of good comes from colleges not requiring test scores. While most benefits are seen as wins for students, there is a catch. A relaxed testing policy does not make a highly selective school less choosy; in fact, it can boost a college’s popularity, increasing the imbalance of available spots and demand for them. Colleges that were already sought after reached record high levels of interest in 2020—especially in their early application rounds—resulting in record low early admit rates. Strong test scores can help an applicant stand out in a crowd.

Sending scores may imply a greater likelihood of admission. That is part cause and part correlation.

Most colleges have kept private the admission rates for test submitters and non-submitters. However, a handful have released this information. Last month, we shared a sampling of several well-known colleges with competitive admissions and in every case there was an apparent edge gained by submission of test scores.

While strong test scores probably played an additive role for applicants in pools like these, it’s also true that most of the highest scoring test takers are also high academic achievers. They were admitted with test scores, but may have been admitted without them. So while the presence of scores may correlate to higher admission rates at some schools, it can’t be said that sending scores will automatically lead to better outcomes.

The importance of scores may differ between Early and Regular Decision rounds.

It’s easy to overlook that running a college means running a business. The admissions office plays a critical role in the business health of the college, especially at schools that are heavily tuition-dependent and have tight enrollment targets. If you work in college admissions, you work in forecasting, and forecasters prefer placing informed bets.

When a student applies early, the college already knows a little more about them. Most notably, the college knows that, if accepted, that student is more likely to enroll.

The early rounds are also often when recruited athletes are encouraged to apply. And they’re when students who have already engaged deeply with the college tend to apply. So it’s a little easier to admit a student without a test score if so much else about that applicant is known.

In many cases, the regular round is more competitive. Part of the class is already in place. The regular round is larger, more varied, and non-committal. At Rice University, for instance, the yield rate for Class of 2025 Early Decision admits was 97%, whereas the yield rate for Regular Decision admits was 33%. Colleges are not merely contemplating who to accept but also who will enroll if accepted. A test score is one of the inputs that helps them gauge the likelihood an admitted student will enroll.

Submitting a score in the regular round could be thought of as a form of demonstrated interest, in effect. Before a score says anything about how an applicant might perform as a first year student on your campus, it first helps place odds on that applicant even choosing to attend your college.

Most colleges see their yields drop as scores rise because those with the very highest scores tend to have an array of alternatives. Colleges that offer merit aid will use discretionary funds as incentive to improve their chances of yielding their strongest admits by discounting tuition strategically. At such schools, good test scores help earn applicants admission. Better test scores may help earn them rewards.

There has been some speculation that models will require some adjustments in the next cycle due to shifting yield assumptions tied to an increase in non-submitters. When scores were missing altogether, colleges didn’t necessarily know how to forecast yield. We’ve heard stories of non-submitters accepting offers at higher than expected rates at some schools. If true, it’s possible that fewer non-submitters would be admitted to such colleges in subsequent years.

The importance of scores depends on where you are and where you hope to be.

The term “test optional” has become a household phrase, but it lacks crucial context for the student in your particular household. Since admission decisions are made contextually, holistically, situationally, and individually, students should take the same approach when making their choices. Start by answering these questions:

- Do most students from my high school usually take the SAT / ACT?

- What are the average test scores from my high school?

- Will most applicants—particularly from backgrounds like mine—submit test scores to my target colleges?

- What are the average test scores at my target colleges?

These figures have traditionally been very easy to find on high school profiles (which get included in college applications, by the way) and college websites. Because pandemic-era data will be anomalous in many cases, obtaining reliable data may require looking at longer historical trends and speculating (and inquiring) about where testing trends are headed in specific settings.

When researching a certain college, try to push beyond “test optional” to get a better sense of the true role of testing. Some colleges will state plainly that testing is not important. Others may use subtle qualifiers like “plus factor” or “appreciated”. You may even encounter more pointed stances, such as: “still important”, “recommended”, “preferred”, or “expected”.

Try to glean where your college lands on the test optional dial. Was it test optional before the pandemic? If not, is it now permanently test optional or still framing the policy as a temporary allowance in response to a pandemic? Assess the likelihood of returning to recommending or requiring test scores in the future. We expect some colleges, especially those that are extending test optional policies one year at a time, will eventually revert to requiring or strongly recommending scores. Stanford’s evolving policy language is case in point. Previously, Stanford noted: “We expect to reinstate the SAT or ACT testing requirement for the Class of 2026, entering in Fall 2022.” As the pandemic continued to interrupt test site availability, Stanford amended its policy: “We recognize the ongoing challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic, including limited access to admission testing worldwide, and are extending this year’s test optional policy to a second year.”

Colleges have gone test optional while students have stayed “test optimal.”

Students who are disadvantaged or discouraged by testing now have more college possibilities than ever before, and that’s the best part of the expanded test optional landscape.

There are other students who see the combination of relaxed testing policies and the reopening of test centers as an opportunity to highlight a strength. Instead of focusing on something to forgo, these students know their strong scores will be a valuable and recognized piece of the review process at many schools, especially where demand for admission outstrips supply.

Such students see testing as an expedient way to gain an edge by presenting a standardized test score that is familiar and trusted. This is the pragmatic mindset we’ve often encouraged, one that neither overestimates nor underestimates the role of a test score.

Even for the class of 2021, which had its testing calendar upended, the data on higher scoring students revealed an appetite for testing, when given the opportunity to test. While overall SAT takers were down 32%, those scoring in the 1400–1600 range were off by “only” 18%. Of course, high scorers are more likely to test early, so some of them secured scores pre-lockdown. Others took extra(ordinary) efforts to find opportunities to test.

In informal conversations with both students and college admissions officers, it’s been suggested that SAT or ACT scores could now be thought of as super-activities, special achievements, or awards. They are not required, but they are known to add value. They distinguish an applicant and earn extra consideration.

If you’re on the fence about sending a score, you probably should send it.

If you feel like your scores are borderline, get advice from a counselor, but know that you are probably better off sending them in most borderline cases.

Yes, the reported range of test scores at many colleges has inched up this year; yes, that can be unnerving; no, your good score is not suddenly too low. If the range is higher, it’s because the lowest scores were removed from the average due to test optional policies. But a good score is still a good score, and it makes the same impression that it did when scores were required.

If you hide a score, that omission may be ignored, but you leave open the possibility of inference on the part of the reader. Did this applicant test or not? Was their score so low they wanted to conceal it? (If you had the chance to turn a B+ into a Pass/Fail, would you? Or might that wrongly imply you were hiding a C-?)

Don’t overthink it. If you are truly on the fence, then chances are your score is not low enough to actually hurt your chances, whereas withholding it adds an element of speculation.

And if your score falls toward the lower end of the college’s range but is one of the higher scores in your local context, it will be viewed supportively.

“We’re not just looking at students within the context of our own middle 50 percent, but how the student has succeeded within the context of where they’re from and their community and their high school.”

— Mari Prauer, Senior Assistant Dean of Admission, Colgate University

Computer-based SAT/ACT testing will be widely available in the next 1–2 years, creating another decision point for students.

ACT and College Board have been piloting computer-based delivery of their respective tests for some time and are expected to provide updates in the new year. These tests were initially rolled out on a limited scale overseas and in contracts with school districts.

Our current best guesses as to when digital testing will be widely available are:

- Class of 2023: possibly

- Class of 2024: probably

- Class of 2025: most definitely

Compass has on-demand practice tests on a digital platform available for individual students and class-wide events. The diagnostic and experiential benefits of these practice assessments were especially felt when social distancing measures were in full effect, and their popularity continues to grow as they allow students to gain comfort with this new form factor.

Individual families and school counselors can contact us to schedule a digital practice test and to then receive a timely and sophisticated analysis of one’s testing performance.