Compass’s Adam Ingersoll and Eric Anderson recently joined with Marco Learning’s John Moscatiello in a webinar about all things AP. Their discussion and Q&A inspired us to prepare a one-stop resource with information about AP Exam scoring, trends, practice testing, and preparation, as well as an examination of the role APs play in college admission.

The webinar can be found here.

What Can Students Expect for APs in 2022?

The pandemic impacted AP performance significantly in 2021, with the lowest scores and largest exam drop in AP history. Will exam levels and scores bounce back?

Many students expected a disaster in the 2020 AP season. Schools were scrambling to finish the year, and College Board had to devise short, at-home exams that covered abbreviated course content. After all the trepidation, though, scores fell in line with historical patterns.

The same cannot be said of 2021. Disrupted learning in 2020 meant that many students were overcoming deficiencies at the start of the 2020-2021 academic year. Fewer students were prepared to take AP courses and, unlike in the previous year, College Board expected students to cover the full AP course material.

The end result was the largest drop in test-takers and scores in the program’s history.

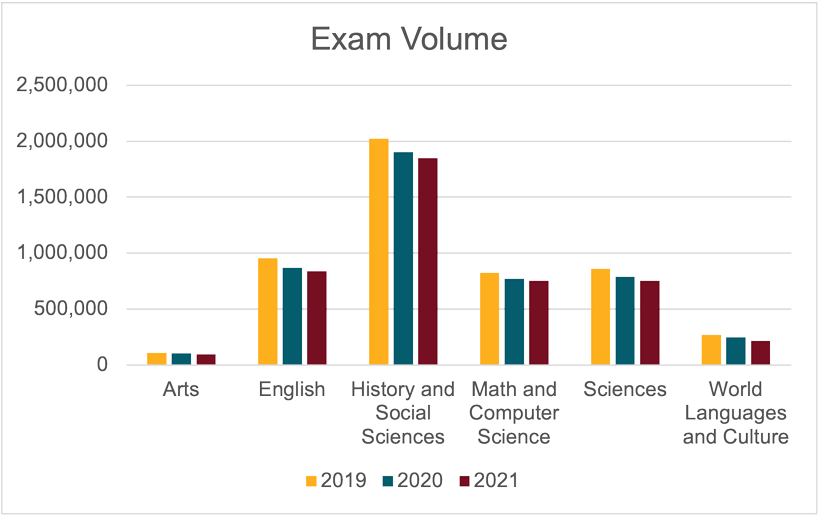

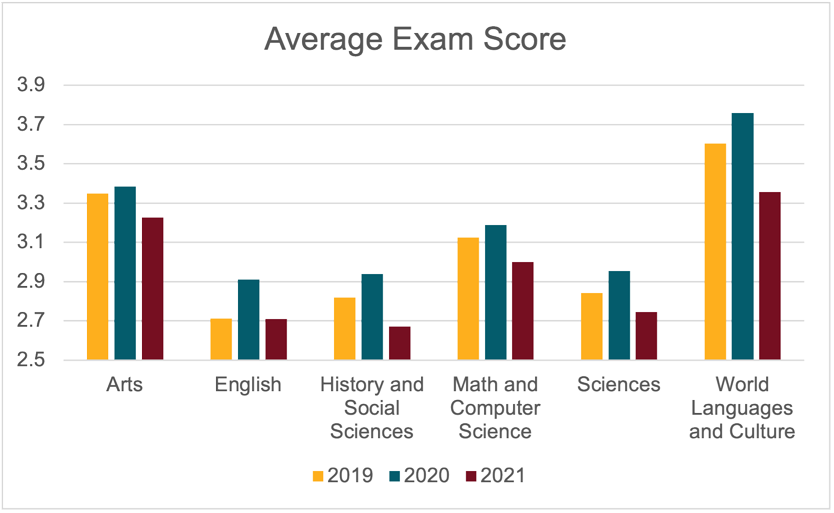

- Exam volumes fell 4% from 2020 and 10% from the pre-pandemic numbers of 2019.

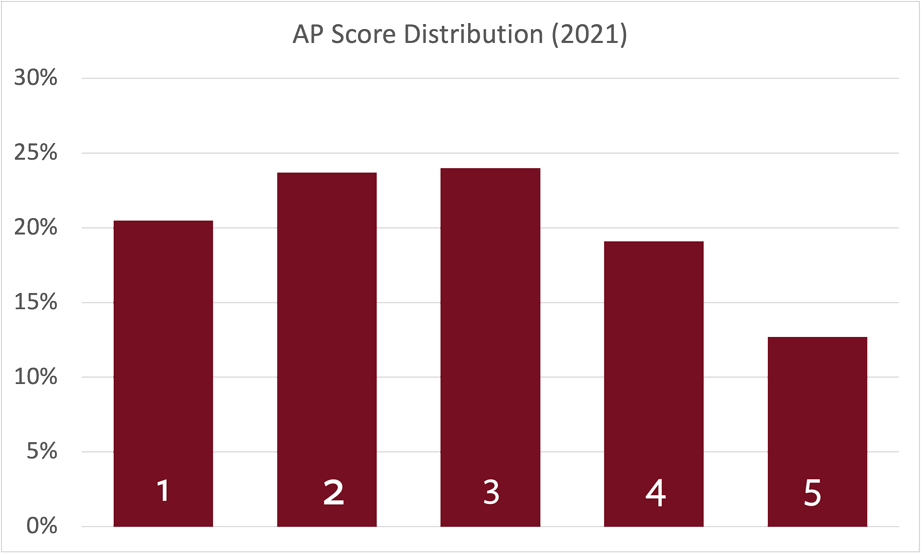

- The average exam score of 2.80 was down from 3.03 in the prior year and is the lowest on record.

- The score declines occurred across the board. 34 of 36 exam subjects saw lower scores. Some fell as much as a half point from the previous year.

- There were the most 1s in program history and the fewest 5s since 2013.

- Hardest hit were courses that depended on cumulative learning such as World Languages, where the number of top scores was almost halved.

Students taking the APs in 2022 have spent 2 years studying during a pandemic. More schools have been able to return to in-person instruction this year, but the challenges and deficits have not disappeared. We may continue to see weakness in AP performance, as College Board has said that it will not be reducing the content covered by the exams.

English Language and English Literature scores may be a bright spot, as College Board is expected to favorably adjust its scoring guidelines.

A score of 3 on an AP is meant to equate to a grade of C to B- in an equivalent college course. A recent review by College Board showed that the scoring of the English exams was underpredicting student achievement. While College Board has not indicated how much of an adjustment will take place, it should be good news for current students.

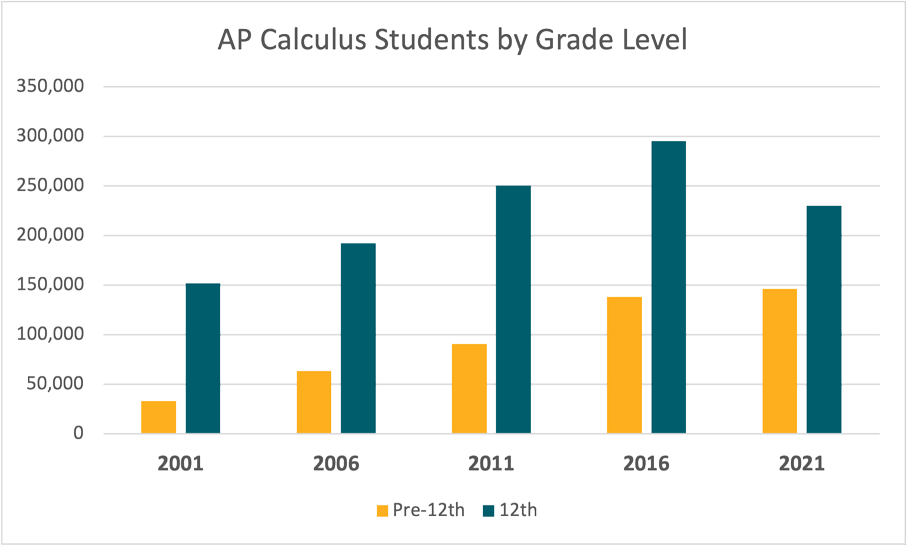

The number of students reporting AP scores for admission continues to rise and that trend is likely to continue. As of 2020, 11th graders became the largest consumers of APs. 63% of APs are now eligible for admission use.

As colleges continue to grow more competitive, sophomores and juniors have looked to APs as a way of boosting their weighted GPAs and academic rigor. As much as we can decry the transcript arms race, there are no signs of its ebb. This trend has led students to take APs earlier and more often. Unlike exam scores and final grades from senior year, sophomore and junior results can be reported to admission offices.

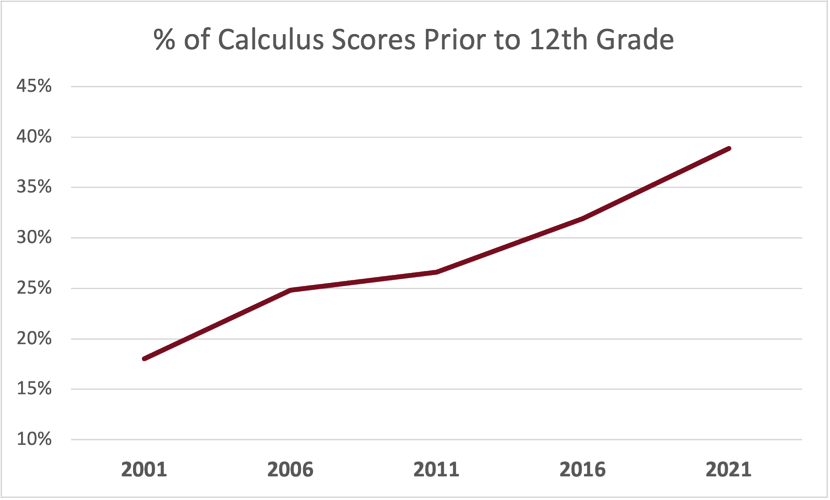

While some of the change can be attributed to newer APs growing in popularity, the trend can also be seen in program stalwarts such as Calculus AB and BC. The courses were long the domain of seniors. In 2001, only 18% of students took AP Calculus before senior year. By 2021, that had grown to 39% of Calculus exam takers. These younger students also outperform seniors, earning 50% of all 5s on the Calculus exams.

This trend is not viewed positively, even among – or especially among – math teachers. A decade ago, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics and the Mathematical Association of America warned against the focus on calculus as the “ultimate goal of K-12 mathematics curriculum.” Students, parents, and professionals interested in understanding how high schools and colleges are trying to rethink “the rush to calculus” should read the National Association for College Admission Counseling report “A New Calculus for College Admissions.” The report reflects how deeply embedded calculus – and AP Calculus, in particular – is in the consciousness of admission officers and students, despite efforts to explore alternative math pathways such as statistics. As one dean of admissions put it, “Calculus is the gold standard that people in this business use as a shortcut.”

Traditional paper-and-pencil exams will be the rule.

The abbreviated at-home exams of 2020 are unlikely ever to return. In 2021, there was a confusing mishmash of full-length exams given in paper-and-pencil and digital formats, in-school and at-home. Things will be more streamlined in 2022 and back to (almost) normal. The only exams remaining computer-based are AP Chinese and AP Japanese. A very limited number of schools will offer digital exams for AP English Literature and AP World History. If you are part of that pilot program, you will have already heard about it from your teacher.

Considerations When Testing and Reporting

AP grades are important, but in an era of grade inflation and in the absence of Subject Tests, strong AP scores stand out.

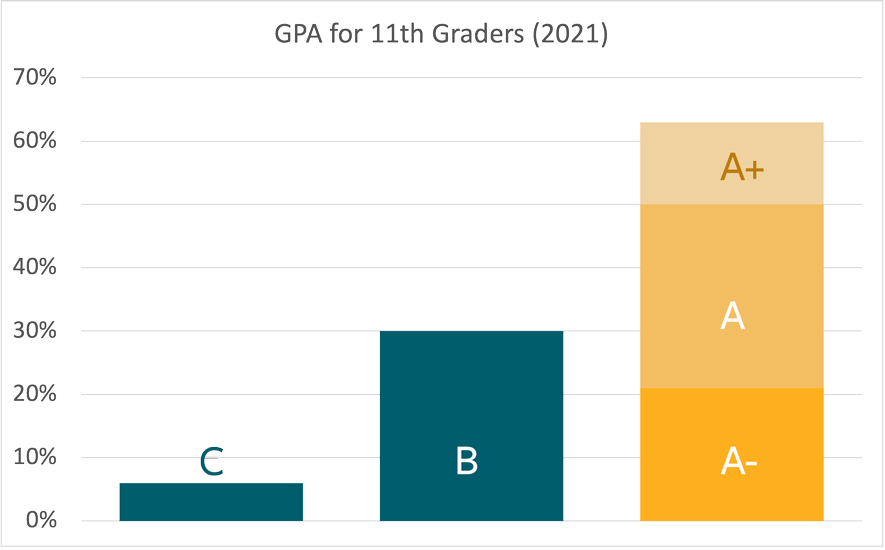

According to College Board, 63% of juniors reported A averages in 2021. At the most competitive colleges, a high GPA is necessary but not sufficient to gain admission. AP scores, overall, are more evenly distributed, and the diversity of subjects allows students to demonstrate proficiency within their academic niche.

Where do top scores put students relative to their peers? In a typical year, about 50,000 sophomores and juniors have 5s to report to colleges in AP Calculus, which is almost identical to the number of students who earned 800s on the Math Level 2 Subject Test. About 12,000 students are in the same position in AP Chemistry and AP Biology. In the final years of the Subject Tests, that is about the number of students earning 800 in Chemistry and 780 or above in Biology. The APs were never designed to be admission tests, but they have inherited that mantle at many universities. They – along with their IB counterparts – are one of the few measures that admission offices can use as standardized indicators of academic performance.

In the past, Harvard has stated that AP and IB scores were the best predictors of success. Subject Tests – now canceled – came in ahead of high school GPA as the next best indicator.

Take the tests. Students often do better than they expect on exams where earning 75% of the points can often mean a 5, and a 3 can be earned with around 50% of the points.

Each year at least one-third of the students taking an AP course choose not to take the associated exam. The introduction of fall fee payment has reduced those opt-out numbers slightly. At best, a missed exam earns a partial refund of prepaid fees. Taking the exam gives a student a shot at earning course credit for college and the possibility of having a useful score for college applications. It’s easy to misjudge your chances on AP Exams. The scoring is byzantine and accurate practice test grading requires outside expertise. Students are unaccustomed to tests where 50% is a passing grade and 75% earns a top mark.

But won’t a low score reflect poorly on you? See the next tip!

You can be choosy about what to report to admission offices. Competitive schools usually expect 4s or 5s. Report your 3s after you get accepted!

While there is no such thing as Score Choice with APs – all scores are included as part of an official College Board report – self-reporting is an even better option. At virtually every college, you only need to list the scores you want to self-report with your application. For students applying to highly selective colleges, this would likely be limited to their 4s and 5s. Save the added fees and hassles and send an official score report – if needed – after you receive your acceptance letter.

At schools such as the University of California, “Test Free” only refers to the ACT and SAT. AP Exams are an excellent way of demonstrating mastery.

UC Berkeley, for example, not only accepts APs, but also notes 3 different uses when gauging academic performance during its holistic review: (1) the number of AP courses taken, (2) the grades achieved in those courses versus other UC applicants at the student’s school, and (3) the student’s scores on AP Exams. [The same is true of IB programs and exams.] Perhaps it should not be surprising that Berkeley received the most AP score reports of any college or university in 2021, even though it is smaller than other universities on College Board’s list of top recipients.

AP Exams fit well with the Test Optional philosophy adopted by many colleges during the pandemic. Students are able to choose how they want to present themselves with the SAT, ACT, and APs. Are you a good test-taker? An ace at Calculus and Physics? Fluent in Spanish or French? While colleges like to emphasize the flexibility of this approach (the University of Michigan even labels itself Test Flexible), the admission competition can still be daunting. The flexibility has given rise to even more applications. Single-digit acceptance rates have become far too common. Harvard accepted only 1 student for every 29 applicants in 2021. First-year applicants to UCLA fell just short of 150,000 for the fall 2022 class.

Optional or not, test scores represent one way in which applicants can distinguish themselves. There is also no reason that students have to make the same decision regarding AP scores that they do with SAT and ACT scores. During the most recent Early Decision cycle at Emory University, the Dean of Admission pointed out that “of the 29% of admitted applicants who chose not to submit a score, many chose to submit AP results in lieu of SAT or ACT scores.”

Assessing the Costs and Benefits of APs

Choose quality over quantity. Focus on courses that matter to you. Weak grades or scores won’t help at competitive colleges.

One problem students face when deciding how many AP classes to take is that they always seem to know someone who has taken more – especially if they start hanging out on Reddit. After all, College Board reported that in 2021 there were 191 students with 20 or more AP Exams and 2 students with 30! These outliers have little to nothing to do with what students should actually be considering.

The admission department at the University of North Carolina studied what it referred to as the “more-rigor-is-always-better philosophy” and found mixed results. It concluded that college-level courses (it grouped AP, IB, and Dual Enrollment together) in high school were predictive of success at UNC, but only to a point. Students with 5 college-level courses in high school had higher GPAs than those with 0 or 1 but had virtually identical GPAs to those with 10 or 11.

Some universities are making an effort to de-escalate the race-to-rigor. The University of Michigan happily accepts AP scores, but it also recognizes, “Where AP is available, excessive AP participation is neither required nor encouraged.”

That leaves the student to ponder, “What’s excessive?” One indicator of excess would be an AP course load that undermines, rather than supports, a student’s goals. One study found, for example, that students taking an AP science course over a non-AP course ended up with lower GPAs (unweighted, at least) because of the impact on their other classes. And that was with a single AP class. Parents and students need to assess the costs and benefits of taking college-level courses too early or too rapidly.

The ideal number APs for highly competitive colleges is often discussed, but usually hinges on personal anecdote.

In the absence of firm advice from colleges, students tend toward speculation.

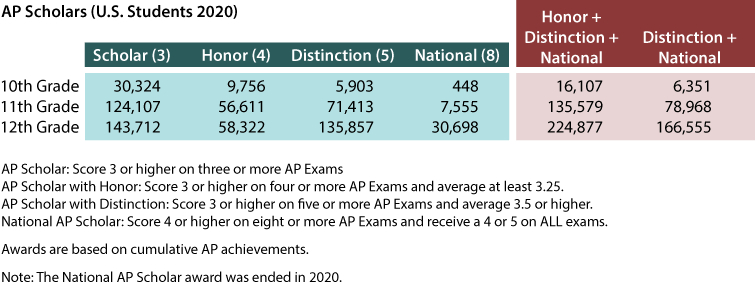

College Board’s AP Scholar awards give some insight into students’ AP taking behavior. The awards require students to get at least 3s on their APs (4s or 5s in the case of National AP Scholars). The awards are based on cumulative numbers throughout high school. For example, a student might be an AP Scholar (see table for definitions) after sophomore year, add more successes and become an AP Scholar with Distinction after junior year, and add even more top scores in senior year to become a National AP Scholar. [Note: In its own effort to deemphasize excess rigor, College Board retired the National AP Scholar designation for 2021. The program now tops out at w/Distinction.]

By the end of 10th grade, 46,431 U.S. students had scored well on 3 or more APs (total across all awards). Only 6,351 of those had 5 or more such scores (w/Distinction and National). After junior year, those numbers increased to 259,686 and 135,579, respectively. Among all of the students participating in the AP program, only 7,555 juniors had taken 8 or more APs and received no scores lower than 4.

How many students apply to college with six to eight 4s and 5s? Based on the data above, Compass estimates that between 15,000 and 20,000 students fit that definition. That is approximately 0.5% of all high school graduates. Many of the “recommended number of APs at College X” that students read about online are counting those taken in senior year and can be intimidating to students thinking only of courses completed before applications are submitted.

Colleges don’t expect applicants to take every AP offered at their school. Or to even have AP courses at their schools.

While some high schools lack the resources to offer AP courses, others have chosen to scale back the program. Most AP courses are designed to mimic general, introductory college courses. College, however, is not made up entirely of general, introductory courses. Some high school faculty appreciate the depth or detours they can provide in college-level courses when not restricted to preparing students for a national exam.

Colleges understand the diversity of course offerings, and there is no minimum level of APs required.

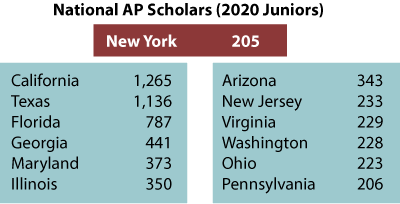

A state-by-state look at the AP Scholar data shows why colleges must account for local conditions and student preference when assessing AP numbers. New York is the fourth most populous state, has high standardized test scores, and its students are well represented at any top college. When it comes to elite AP performance, though, the state’s numbers appear abysmal.

Florida – with a similar population – has almost four times the number of 11th grade National AP Scholars. Even far smaller states such as Arizona, Maryland, and New Jersey rank above New York. On a per capita basis, Kentucky outperformed it.

New York students still take a lot of APs, but they don’t take them as aggressively or as early as in many other states. Scarsdale High School, a top New York public school, gained renown when it rejected APs almost 20 years ago. Many of the top independent schools in New York City don’t offer AP classes – preferring to set their own academic standards. In short, New York is evidence to students everywhere that success can be found without fitting in 5 APs by sophomore year.

If you want to take an AP Exam that your school does not offer – or you are a homeschooler – start planning early.

Homeschool students and those at small schools may find external AP courses to be an excellent way to study challenging material and be recognized for it by colleges. They can turn to any number of online providers and self-study options for AP courses. Taking the actual exam, though, can be more daunting. It’s not as simple as registering for the SAT with a few clicks. Students need to locate an approved school that will order and administer a test for them. Many schools restrict testing to their own students, so start early, stay flexible, and be polite! Exam orders must be submitted by schools by November 15th, so reach out to local AP coordinators well in advance.

The college credit from APs may save you money, allow you to place out of introductory courses, or even graduate early. These benefits don’t apply to all students and all courses.

College credit policies vary widely. Approximately 30 states have laws requiring their public institutions to recognize AP credit. In assessing whether to allow credit, colleges look at which of its own courses align with the AP course, how extensive the course of study is, and how prepared AP students are compared to those completing the college equivalent. Many universities look to their faculty to make these decisions, so the minimum scores can vary from department to department. College Board has a site showing policies across the country, but Compass recommends that you visit college websites for the latest and most detailed information. The University of Pennsylvania is a good example of a school that is choosy about what courses and scores to accept. Twelve AP courses earn no credit or benefit. No scores of 3 are recognized. Depending on the course, 4s may have no benefit or fulfill a requirement without providing course credit. A limited number of 5s receive course credit.

Even with strong AP scores, studies have found that many students choose to repeat the classes in college.

AP courses do not come without a cost (above and beyond the $96 fee).

AP courses are sometimes criticized for the sheer volume of material covered and the burdensome level of homework. One study found that an AP course was associated with more than double the negative stress levels as a non-AP course and a lower degree of confidence. Another study found something that will come as little surprise to AP students and their parents: “By far, the most commonly reported adverse consequence to AP and IB participation was fatigue [from lack of sleep].”

There are educational rewards for taking a rigorous course schedule, but APs are far from the only path. Weigh the impact of AP workloads before finding yourself overcommitted. If you have concerns, speak to your counselor and your teachers for recommendations and seek out the experience of your fellow students.

Preparing for APs

Take at least 1 practice test under realistic test conditions. Maximize your points as efficiently as possible by understanding the scoring rubrics for free-response questions (FRQs).

Stamina is important, time management is critical, and students benefit from practicing on a full test under accurate conditions (i.e., no cell phone distractions). On the AP English Language exam, for example, students must transition from a fast-paced multiple-choice section with only about 1 minute per question to a 2-hour free response section with three essays. It’s all too easy to find that you’ve misallocated your time.

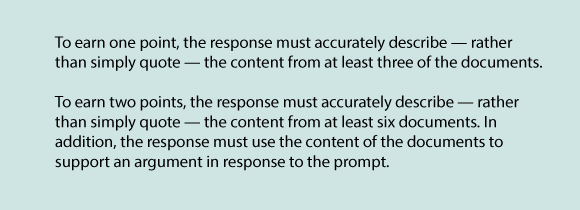

FRQs are graded by trained experts. Your essays and solutions are not graded holistically (“Good essay. I give it a 5 out of 7.”). In order to provide consistent scoring, graders must follow specific rubrics that dictate what elements of an answer deserve points. On the AP U.S. History exam’s document-based question (DBQ), for example, students can earn 0, 1, or 2 points by providing evidence from the documents:

A middle ground of describing the content from five documents just lengthens your response without adding the second point to your score. You can receive an additional point for providing Evidence Beyond the Documents, but not if the evidence is the same that you used to gain a point for Contextualization. In short, your response must be well-diagrammed to hit on the various scoring opportunities. Length alone does not guarantee a higher score.

While it is possible to score your own work, it’s more effective to have a third-party expert do it for you. For most AP subjects, Compass has scheduled testing opportunities for its students. Contact us for more information.

Course and Exam Descriptions and Scoring Rubrics and be found at AP Central. Here is the rubric for the AP History exams.

Start your exam preparation at least a month before test day.

You may find yourself in unique situations with each of your courses. Perhaps you’ve been keeping pace assiduously with AP Chemistry while rushing through your homework in AP World History. You may be able to prepare for Chemistry with a sample test, some practice questions, a review of scoring rubrics, and a quick content review.

In World History, on the other hand, you may be looking at more extensive review. It’s best to spread the work over several weeks – unless you don’t have several weeks – rather than trying to cram all of the material. Make a schedule and then stick to it. Don’t forget to incorporate material you haven’t yet reached in the course.

Consider tutoring or a review course.

A tutor can help keep you on pace, identify trouble spots, provide valuable feedback on practice problems, and identify and remediate content gaps.

In the final weeks of the class, teachers often have a goal of getting as many of their students as possible to pass the course and pass the exam (3 or higher). Your goal is likely higher than passing. Compass has expert instructors in every AP subject. Most of our AP tutoring is done one-on-one online. Contact us to set up a program or to discuss your situation with one of our directors.