For a breakdown of COVID-19’s impact on admission and testing broadly, see: Impact of COVID-19 on College Admission and Testing

Key Takeaways:

- In Spring of 2020, traditional AP Exams did not take place. AP Exams were administered as 45-minute, web-based, free response exams.

- At the end of September, 2020 most colleges seem to have settled their 2020 AP credit policies. Most colleges decided to confer credit for the 2020 AP Exams as though it was a normal year. Some colleges changed their credit policies and/or required their own placement exams, some made no formal change in policy, and no school that we are aware of fully refused to accept the results: https://www.compassprep.com/2020-ap-exam-policies/

- If conditions allow, College Board plans to return to standard AP Exams in the spring of 2021. For help preparing for these exams, contact Compass to learn about our AP tutoring. We also offer academic tutoring in over 50 subjects and have a special Study Skills and Organization Coaching program to supplement at home learning.

8/13/2020: Compass Webinar on 2020 AP Exams

Directors Eric Anderson and Dulcie Head hosted a presentation about the completed 2020 AP Exams.

8/4/2020: Most Scores from the 2020 AP Exams Released

Which AP Exam scores have been released?

AP scores have been released from exams taken during the primary testing window (May 11 – May 22) or make-up testing (June 1 – June 5) window. Students who tested in the exception testing window (June 22 – 30) or emailed their answers in will receive their scores by August 7.

What is the rescoring policy?

In a year when full-length AP Exams are administered on paper, in classrooms, students contesting their scores have an option to have their multiple choice rescored by hand. They could not, however, ask for re-scoring of FRQs.

As the 2020 AP Exams were administered sans multiple choice, a multiple choice rescore is clearly not an option. For the 2020 AP Exams, students who receive a 1 or 2 can ask that their free response questions be rescored. Students who receive a 3, 4, or 5 cannot ask that their free response questions be rescored.

Students with incomplete exams may test during the week of August 24-31.

For any students who were unsuccessful in submitting an AP Exam in the primary testing window, makeup testing window, or exception testing window, the College Board has offered one “final” chance to take a 2020 AP Exam: the August AP Testing for Students with Incomplete Exams testing window on August 24-31. Here is the exam schedule: August AP Testing for Students with Incomplete Exams.

The 45-minute, online, remote format, same-day/same-time worldwide scheduling, exam portal, and submission options remain the same. Students must use emailed e-tickets to access the exams, which will be sent to them two days before the exam (no e-tickets will appear in My AP).

Who is eligible for the August Incomplete Exams testing window?

Eligible:

- Students who started an exam during any of the three previous testing windows but failed to submit all or part of it. The failure in submission could be during at any stage in any exam window. Choosing not to use the email submission option also counts as failure to submit.

Not Eligible:

- Students who did not attempt to test during any of the previous three testing windows.

- Students who successfully submitted their exam in its entirety during any of the three previous testing windows but are dissatisfied with their score.

Eligible students were emailed during the week of July 27. Principals and AP Coordinators were also emailed.

What advantages and challenges confront students preparing for the August Incomplete Exams testing window?

Each year, to perform at a high level on their APs, students marshal study effort, course-specific resources, teacher support, tutor support, and peer collaboration to mastering college-level material—all of which come to a head just before the AP Exams themselves in May. The more those resources are abundantly and vigorously used, the likelier the success.

As anyone who’s ever tried to perform integration after even a few months off of calculus can attest, information gets stale, techniques get rusty, and what was once second nature can become a slow, uncertain process. Students using this final testing window will be taking their exams three months after the conclusion of their remote, online AP courses, and a half-year since they’ve received any kind of in-person instruction. Teacher support may be compromised as many of last year’s AP teachers will have redirected their efforts to teaching a new class the beginning of the curriculum. Study groups may be long disbanded. Peers may be focused on the coming school year. Students seeking to take advantage of this testing window may face conflicts with their new class schedule. Seniors who’ve graduated high school and are fully focused on college, ready to put a difficult senior year in the rearview.

Now, the 2020 AP Exam format, the online AP Exam submission portal submission are known entities whose shortcomings have work-arounds, such as emailed submissions, and whose quirky preferences, such as incompatibility with HEIC files, are more widely known. The advantages of knowing more about how to get an AP exam submitted, however, are to a degree counteracted by the disadvantage of testing so late.

How many students will test during the August Incomplete Exams testing window?

It is likely that only a small percentage of AP students will test at the end of August. Although the College Board has not released data on the exams beyond the primary testing window, the percentage of students who started their exams but were unable to submit them from the primary testing window offers a rough estimates of how many students were not able to submit exams in the makeup and exception testing windows:

- Primary Testing Window: 92.8% of 4,663,626 students who began the exam completed the exam, leaving 333,768 who started but did not complete the exam.

- Makeup: If an estimated 95%* of 333,768 who began the exam completed the exam, then 16,688 students would have started but not completed the exam. (*The estimate of 95% comes from the reasons that a higher percentage of students would be likely able to successfully submit exams during makeup testing than during the primary testing window: 1) the emailed submission option that was introduced in week two of the primary testing window was again offered in the makeup exam testing window; 2) greater awareness, resources, and communication regarding submission methods that were less likely to work; 3) fewer students testing lessened the strain on the submission portal.)

- Exception: If an estimated 95% of 16,688 who began the exam completed the exam, then 804 students would have started but not completed the exam, or not taken the exam.

- August AP Testing for Students with Incomplete Exams: under 1,000 students, or about .022% of all 4,663,626 students who began an exam during the primary testing window.

Even a lingering fraction of students, who, through no fault of their own, were unable to submit exams, poses a loose end that could damage both the students’ right to take the exams and the advantages of credit-conferring scores, and the College Board’s mission and reputation. The AP Exams exist in a different and, in some ways, more hostile testing and cultural landscape in August than they did in the April lead-up: students filed a class action lawsuit backed by FairTest, started petitions for rescoring, and the media widely reported on students who had poor experiences with the exams.

How do you share exam results with colleges?

Students could have sent scores for free, but would have had to do so without knowing their scores. They would have had to select this free score send option by June 30.

After June 30, students must pay a fee to send scores. When they do so, their entire score history goes out to schools they’ve indicated they want to share their scores with UNLESS they request to withhold scores. To withhold scores costs $10 per score per school. Here are instructions for doing so: https://apstudents.collegeboard.org/score-reporting-services/withhold-scores

Primary takeaways from the 2020 AP Exam score data.

Scores from the 2020 AP Exams varied more than they did in prior years, but they varied by significantly less than what many may have expected, given the dramatic alterations in format (45-minute, no multiple-choice, all free-response) and delivery model (online, at-home).

As we expand upon below, we compiled score profile data from AP Exams going back to 2014 and examined the year-over-year variation in scores from 2014-2019. We found that, on average, scores varied by 0.5%, with a standard deviation of 2.2%. Any score that varied by over +/– 4.3% from the prior year’s exam (over two standard deviations) experienced an “abnormal” shift. We call these scores outliers.

While the 2020 AP Exams do overall have a higher percentage of outlier scores than in previous years (32 / 180, or 17.8%), most scores (148 / 180, or 82.2%) do fall within the normal range of year-over-year variation. It is also worth noting that the largest individual shifts in percentage of students attaining a specific score were around 10%, not 20% or 30%. In many ways, these results are remarkably consistent with prior year score profiles given the dramatic change in exam structure and delivery. Yes, even amidst the pandemic, there are things the College Board probably could have done to lower and improve these numbers, such as providing the backup email submission option from the very first day of the primary testing window. But these numbers could have also and more easily gone a whole lot higher and worse.

It is worth remembering that test-takers go through their exams as individuals, not populations. The behavior of a population might not reflect the behavior of an individual. For example, although English exams were the second most reliable type of test on the 2020 AP Exams by the year-over-year variation, a students who received a passage from the 1800s may have had a tougher (or easier, depending on reading habits and preferences) time than a student who received a passage from the 1900s or 2000s, even though the two testing experiences and their relative difficulties could have averaged out in the data.

Behind each data point is a student. We should be careful not to let the familiar 1 – 5 scoring scale used by the 2020 AP Exams mask that student’s individual testing experience, taken in the midst of this enormously difficult and ongoing trial.

How do score distributions from the 2020 AP Exams compare to those of previous years?

The percentage of students who scored a 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 on a certain 2020 AP Exam offers a glimpse into how the 2020 AP Exams measured up to traditional AP Exams. These data cannot fully answer the deeper questions and controversies that have swirled about since the College Board’s announcement that the 2020 Exams would be 45-minutes, at-home, and online. Among the questions that remain open to interpretation and debate:

- How secure and impervious to cheating were the exams?

- What does a 4 (or any score) on a 2020 AP Euro Exam (or any 2020 exam) say about a student’s mastery, compared to a similar score and exam from a traditional year?

- How well does a 2020 AP Exam predict performance? How ready will students receiving qualifying 2020 AP scores be to bypass entry-level college courses as compared to prior years?

- Given the smaller sample size of questions, to what extent could students control their score outcomes? Did a student who would’ve gotten a 5 on a traditional AP Exam get a 4 because they were unlucky at what the shortened exam covered; did a student who would’ve gotten a 4 on a traditional AP Exam get a 5 because they were lucky?

- Were the 2020 APs an innovation-by-necessity and imperfect solution to the blindsiding of the pandemic, or a quantifiable misstep?

These data can, however, offer an imperfect glimpse into how comparable the 2020 AP Exams were to AP Exams given during recent traditional years. Score distributions that aligned closely with those of recent traditional years would indicate exams that, despite their severely altered format and delivery model, were to an extent reliable; scores that diverged sharply from those of recent prior years would suggest exams that were to an extent less reliable.

While some of the 2020 AP Exams indicate a comparable percentage of 1s, 2s, 3s, 4s, and 5s to previous years’s exams (students scored only 0.4% more 5s on the 2020 AP Macroeconomics Exam than on the 2019 version), and others indicate a divergent percentage of 1s, 2s, 3s, 4s, and 5s to previous years exams (students scored 11.2% fewer 3s on the 2020 AP German Language and Culture Exam compared to the 2019 Exam), overall, the score distributions do indicate—by several metrics—an increase in variability due to the format (45-minute, no multiple-choice, all free-response) and delivery model (online, at-home).

A deeper dive into score distribution data from the 2020 AP Exams.

First, a disclaimer: the 2020 AP Exam score distributions are subject to change once scores from exams that were emailed in using the back-up submission option, or taken during the makeup, exception testing, and late August incomplete exam windows, are released. However, because these exams account for only a fraction of the total exams taken, we do not expect to see a major shift in the score data. The makeup, exception, and late August exams should not exceed 7.6% of the total tests administered—the 0.4% of students who had a detected submission error and the 7.2% of students who did not complete their exams, likely due to an undetected submission error.

The 2020 score distributions draw from a slightly different data set, including the primary testing window and the makeup testing window, but not the exception or late August testing windows. Using these data, we can analyze the degree to which the format of the 2020 Exams accounted for variation in scores.

We have compared the relative variation in scores from the 2019 exams to the 2020 exams, two years when exam format and delivery model differed, against the variation from the 2018 to 2019 exams, two years when the exam format and delivery model were controlled. This comparison helps to contextualize the changes in scores from 2019 to 2020.

Even in years when AP exams are administered in their traditional formats and delivery models, some scores (1, 2, 3, 4, or 5) for some exams change more than other scores from other exams. For example, in 2018, here are the percentages of students scoring at a 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 on the AP Physics C: Mechanics exam:

- Percent of students receiving a 5: 30.2%

- Percent of students receiving a 4: 27.3%

- Percent of students receiving a 3: 19.7%

- Percent of students receiving a 2: 12.7%

- Percent of students receiving a 1: 10.0%

In 2019, here are the percentages of students scoring at a 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 on the AP Physics C: Mechanics exam:

- Percent of students receiving a 5: 37.7%

- Percent of students receiving a 4: 26.7%

- Percent of students receiving a 3: 17.4%

- Percent of students receiving a 2: 10.0%

- Percent of students receiving a 1: 8.20%

By comparing the percentages of students scoring at a 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 on the AP Physics C: Mechanics exam from 2018 to 2019, we can see how much each score changed:

- Change in the percent of students receiving a 5: +7.5%

- Change in the percent of students receiving a 4: –0.6%

- Change in the percent of students receiving a 3: –2.3%

- Change in the percent of students receiving a 2: –2.7%

- Change in the percent of students receiving a 1: –1.8%

These data indicate that the largest change in number of students receiving a certain score was those scoring a 5, with 7.5% more examinees achieving the top score in 2019 than in 2018. In both years, the AP Physics C: Mechanics included a 35 question, 45-minute multiple choice section worth 50% of the score, and a 3 question, 45-minute, free response section worth 50% of the score (same exam format). In both years, it was administered in-person (same delivery model).

For any single exam, then, the percentage of examinees achieving a certain score can vary for reasons other than exam format and delivery model. Why? There are variations in difficulty between form codes year over year. The relative rise or fall in popularity of an AP class and exam amongst students can drive high-achievers to self-select into (or out of) a certain course. Better study resources, such as the release of the previous exam’s FRQs can improve student preparedness. Internal adjustments of grading policy, even unofficial, amongst College Board readers can also impact grades.

To control for these and other factors that may impact exam scores from one year to the next and isolate for how much variation in scores may have been due to the 2020 AP Exams’ change in format and delivery model, we need to examine not just how one exam changed, but how all the exams changed, from 2019 to 2020. Then, we need to compare that change in scores to the change that occurred between two years where the format and delivery model were the same, such as 2018 to 2019.

From 2018 to 2019, the percentage of students receiving a certain score for some exams changed more than it did for other exams. For instance, for the AP US History Exam, the percentage of students scoring 1s varied from 2018 more than the percentage of students scoring 2s, 3s, 4s, or 5s. On the 2018 APUSH exam, 25.5% of students scored 1s, whereas in 2019, 24.3% scored 1s. The percentage of students scoring 1s declined by 1.2%, a greater year over year change than the decline in 2s (0.7%), the increase in 3s (0.7%) the non-change in 4s (0.0%), and the increase in 5s (1.1%).

Running the same exercise for all 36 AP Exams for the changes between each consecutive year from 2014 to 2019 allows us to determine the standard deviation on the changes in the number of students with a certain score.

The assumption here is that the score profile (percentage of students with each score) is supposed to be about the same every year. For this reason we have discarded from our analysis any exam in a year when that AP Exam was redesigned, such as the AP European History exam from 2015 to 2016: https://www.compassprep.com/how-ap-scores-have-changed/. This assumption seems to be valid when we consider the average of the change in percentage of students with a specific score across all considered exams from 2014 to 2019—a value of 0.5% with a standard deviation of 2.2%, values low enough to indicate that overall score profiles are not changing significantly, year to year.

We quantify the “normal” variability as within this standard deviation on the change in scores from 2014 to 2019, so we classify “normal” variability as +/-2.2% from the prior year. To determine which exams exceeded this normal variability in the change in scores from 2019 to 2020, we flagged any scores that changed by over 4.3% (two standard deviations) as “abnormal.” We call those scores “outliers.”

How did “abnormal” scores in 2020 compare to those of previous years?

In 2020, 18 of the 36 AP Exams had a score profile where the number of students with a certain score changed by over 4.3% from the previous year. Put another way, 50% of the 2020 AP Exams had a change in the number of scores that was an “abnormally” large change as compared to the change in prior years.

In contrast, in 2019, only 6 of the 36 AP Exams (approximately 16%) had a shift in the number of students scoring 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 that changed by over 4.3% from the previous year.

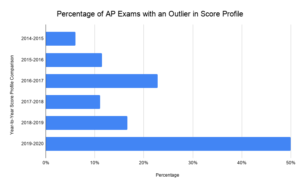

A 50% outlier rate is significantly higher than the outlier rates of the past five years, as the graph indicates.

Percent of scores that were outliers (exams listed in order of degree of variation from the prior year, from most variation to least):

2018 to 2019: 6 / 36 exams, 16% outliers

- AP Physics C: Mechanics

- AP Chinese Language and Culture

- AP Human Geography

- AP Physics 2

- AP Italian Language and Culture

- AP Physics 1

2017 to 2018: 4 / 36 exams, 11% outliers

- AP Physics C: Mechanics

- AP Physics C: Electricity & Magnetism

- AP Statistics

- AP Human Geography

2016 to 2017: 8 / 35 exams, 23% outliers

- AP Spanish Language and Culture

- AP Japanese Language and Culture

- AP Chinese Language and Culture

- AP Statistics

- AP Microeconomics

- AP Art: 2D Portfolio

- AP Human Geography

- AP Art: Drawing Portfolio

2015 to 2016: 4 / 35 exams, 11% outliers

- AP Art History

- AP Computer Science A

- AP Comparative Government and Politics

- AP Art: Drawing Portfolio

2014 to 2015: 2 / 33 exams, 6% outliers

- AP Japanese Language and Culture

- AP Comparative Government and Politics

The 2020 AP Exams had three times as many outlier scores as the 2019 Exams:

- AP German Language and Culture

- AP Art: 3D Portfolio

- AP Art: 2D Portfolio

- AP Japanese Language and Culture

- AP Spanish Literature and Culture

- AP French Language and Culture

- AP Art: Drawing Portfolio

- AP English Literature and Composition

- AP Latin

- AP Spanish Language and Culture

- AP Human Geography

- AP Italian Language and Culture

- AP Macroeconomics

- AP English Language and Composition

- AP Chinese Language and Culture Scores

- AP Physics 2

- AP Psychology

- AP US Government and Politics

In short, it is not accurate to say that the variability that would naturally occur from traditional year to year can account for the different score make-up from 2019 to 2020.

However, it is also not accurate to attribute this shift entirely to the first-order effects of exam format or delivery model alone. There are several confounding factors to consider. These are discussed further below.

Were the 2020 AP Exams harder or easier?

From 2019-2020, across all the exam topics, here are the average changes in the percent of examinees who received a certain score:

- Change in the percent of students receiving a 5: +1.6%

- Change in the percent of students receiving a 4: +1.6%

- Change in the percent of students receiving a 3: 0.0%

- Change in the percent of students receiving a 2: –1.7%

- Change in the percent of students receiving a 1: –1.6%

These data indicate that, while the same percentage of students in 2020 were scoring 3s as they were in 2019, there was over a shift away from 1s and 2s and into 4s and 5s. With a higher percentage of students scoring 4s and 5s, and a lower percentage students scoring 1s and 2s, it is tempting to conclude that it was easier on a 2020 Exam to score a 4 or 5 than it was on a 2019 exam. (This is to say nothing, of course, of the unique difficulties posed by technological issues, learning how to take the 2020 Exams, managing the potential added stress, asynchronous exam review, etc.) The story behind the data, however, indicates that contributing factors outside of the relative difficulty of the exams may have pushed scores higher.

Contributing Factors:

- Self-selection. With the change in the exam format, it is possible that students most likely to push forward with their exam review and adequately learn how to take the tests were those who strongly suspected that they would score well. Students who suspected they would not do well, or who experienced a submission error during the first testing window, might be less likely to test again. Such self-selection of strong test-takers could inflate scores.

- Digital Divide. The degree to which the College Board and its partners bridged the digital divide remains unknown. Despite efforts to provide remote testing tools and internet connectivity to under-resourced students, it is inevitable that certain students were not able to test due to inadequate technology. Excluding a greater proportion of under-resourced students than students who were fortunate to have access to adequate technology may have omitted scores from students who were in compromised learning situations in the first place, with underfunded and non-conducive classroom environments or remote learning exam review options.

- Grading Lenience. Graders reading FRQs can offer more subjectivity than scanning machines running bubble sheets. It is possible that graders came at exams from a posture of understanding and compassion about the challenges faced by students, and this mindset lifted scores.

- Exam Security. The College Board announced that they broke a cheating ring before the primary testing window; Trevor Packer noted that the submission system withstood numerous cyber attacks. Yet the question will remain: did any test-takers cheat and get away with it?

In conclusion, while it may sound surprising, given the drastic changes to the 2020 Exams’ format (45-minute, no multiple-choice, all free-response) and delivery model (online, at-home), the College Board did an impressive job administering exams whose score distributions were comparable to those of prior years.

6/1/2020: Makeup Testing (June 1 – June 5) Begins in the Aftermath of the 2020 AP Exams’ Primary Testing Window (May 11 – May 22)

The College Board released a 2020 AP Exams Data Overview: over 7% of students who started an exam did not submit it, and .41% of students experienced an error.

Mainstream media outlets covered the evolving story of students experiencing technical glitches during the taking and submitting of their AP Exams. The story culminated with a $500 million class action lawsuit against the College Board, filed by students who’d experienced a technological glitch.

The College Board’s data from the primary testing window indicates that 333,768 students of the 4,633,626 who began an exam did not complete the exam, or 7.2% of students. On its website, the College Board celebrated this completion rate in bold lettering: “This year, of the more than 4.6 million AP Exams started during ten days of online testing, an even larger majority of AP students (93%) completed their AP exams than in typical years (91%).”

The statistic may not be as sunny as it appears, given the comparison between a 2020 AP Exam and a traditional AP Exam is not apples to apples. On a traditional AP Exam, students may not complete an FRQ due to running out of time, not knowing how to answer, a mid-test conflict/emergency, or as part of their strategy, amongst other reasons––but not due to a technological error. On a traditional AP Exam, a multiple choice section and multiple FRQs balance out blank FRQs. Not completing an FRQ does not necessarily mean a student would score poorly.

On the 2020 Exams, with only one or two FRQs comprising the entire exam, not submitting any FRQs means students score 0s. It’s unclear how much of the 7.2% of students who began but did not complete an exam includes students who did, indeed, complete their FRQs offline, whether by typing or handwriting, or completed a substantial enough part of them to have a shot at a college credit-earning score, but were unable to submit due to a technological error that is not accounted for in the error rate. The error rate (discussed below) might not include students who finished an exam but were unable to submit due to a frozen submission button, an internet connectivity or compatibility issue, or another unforeseen technological barrier.

The College Board’s data from the primary testing window indicates that there were 19,772 errors detected across 4,633,626 exams. Common errors cited by the College Board include “issues like computer viruses, corrupted files, or unreadable file formats.” One common unreadable file format was likely .heic, the default photo format for iPhone 11s. The College Board did include in its communication that the .heic format was incompatible with its submission system, but inevitably, this was a piece of information some student never came across, overlooked, or otherwise forgot. Because some exams had multiple errors, the percentage of distinct students who experienced errors was lower. A total of 12,752 students of the 4,633,626 who began an exam experienced an error, for an error rate of 0.275%.

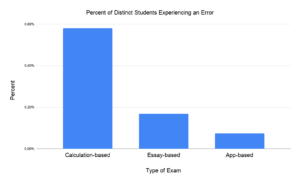

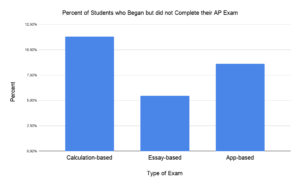

Calculation-based exams saw a higher percentage of students who did not complete the exam than essay-based exams.

A closer look at the data reveals that not all exams were equally error-prone. Calculation-based exams saw over triple the percent of students experiencing an error (0.58%) than essay-based exams (0.17%). App-based exams had the lowest error rate (0.074%).

Calculation-based, essay-based, and app-based are not official College Board distinctions amongst exams, but rather nomenclature that correlates with the preferred (or, for app-based, mandatory) method of answering amongst students. Although the College Board has not released data on students’ preferred mode of submission by exam type, common practices in school suggest that students may be more comfortable with (and thus more likely to) type out responses and then use the copy and paste feature with essay-based exams. Students may be more comfortable with (and thus more likely to) hand-write responses on math, science, or other calculation-based exams. Further cementing this preference could be the requirement from calculation-based AP exams to show the work leading to answers. Students unfamiliar with typing in mathematical or scientific symbols would be saddled with learning or improving new keyboarding techniques––a tall enough order that the path of least resistance would seem to be handwriting and uploading photos.

Typing responses for essay-based exams involved composing a response in a separate word processor and then copying and pasting into the submission window.

Hand-writing responses for calculation-based exams involved taking a photo of the completed response and uploading it via the submission portal.

Recording responses for app-based exams involved recording and submitting within the app itself.

Essay-based exams include: AP Latin, AP United States Government and Politics, AP Human Geography, AP English Literature and Composition, AP European History, AP Spanish Literature and Culture, AP Biology*, AP Art History, AP U.S. History, AP Computer Science A, AP Environmental Science, AP Psychology, AP English Language and Composition, AP World History: Modern

*Note: Although AP Biology does include at least one calculation task, the majority of the tasks ask for short verbal answers supported by analysis. As a result, we suspect many students typed and copied/pasted their results, and so include it as an essay-based exam.

Calculation-based exams include: AP Physics C: Mechanics, AP Physics C: Electricity and Magnetism, AP Calculus AB, AP Calculus BC, AP Physics 2: Algebra-Based, AP Chemistry, AP Physics 1: Algebra-Based, AP Music Theory**, AP Microeconomics, AP Macroeconomics, and AP Statistics

**Note: Music Theory included two FRQs. The first required students to print out staves. The second asked students to use a recording device. Because handwriting and uploading a photo was a requirement, Music Theory is included in calculation-based exams.

App-based exams include: AP Chinese Language and Culture, AP Italian Language and Culture, AP Japanese Language and Culture, AP German Language and Culture, AP French Language and Culture

Calculation-based exams saw a higher percentage of students who experienced an error than essay-based exams.

Students also were not finishing calculation-based exams as frequently as essay-based exams. Calculation-based exams saw over double the percent of students who began but did not complete their exams (11.31%) than essay-based exams (5.47%). App-based exams had an 8.61% incompletion rate.

Certainly, a percentage of students who began but did not complete their exams did so for reasons outside of a submission issue (sudden illness, an emergency, power outage, internet outage, computer running out of battery, etc.), but those reasons alone would apply across exam types and cannot account for the difference in completion rates amongst types of exams. Rather, it seems likely that many students included in the incompletion rates did indeed complete their exams insofar as they wrote their essays, recorded their answers, or solved the problems, but were still counted as incomplete because they encountered trouble in submitting their responses. There is no released data on why each student who did not submit a response ended up doing so. Being unable to submit a completed exam (say, due to a frozen submit button) would not necessarily be understood by the SAT as an error.

All else being equal, the inclination towards handwriting/uploading photos of calculation-based exams and typing/copy and pasting essay-based exams is likely the decisive factor in accounting for the various incompletion rates.

In short, the submission portal handled copy and paste better than photo uploads.

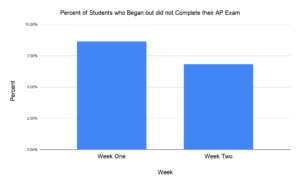

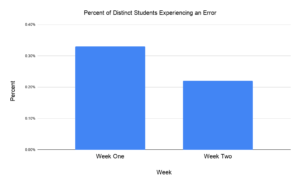

Week Two exams (May 11 - May 15) had a lower error rate and incompletion rate than Week One exams (May 18 - May 22), but the reason may be less about an effective debugging progress than the exam types.

A higher percentage of students completed their exams during Week Two than during Week One. During Week One, 8.65% of students who began an exam did not complete it (and 91.35% did); during Week Two, 6.84% of students who began an exam did not complete it (and 93.16% did).

Likewise, students suffered a lower percentage of errors during Week Two of the Primary Testing Window than during Week One. During Week One, 0.33% of students experienced an error; during Week Two, 0.22% of students experienced an error.

Likewise, students suffered a lower percentage of errors during Week Two of the Primary Testing Window than during Week One. During Week One, 0.33% of students experienced an error; during Week Two, 0.22% of students experienced an error. What accounts for the sinking percentages in errors and incompletion rates as the exams moved from Week One to Week Two? Perhaps the College Board performed effective maintenance on the submission portal and students benefited from advice from their Week One peers on best submission practices.

What accounts for the sinking percentages in errors and incompletion rates as the exams moved from Week One to Week Two? Perhaps the College Board performed effective maintenance on the submission portal and students benefited from advice from their Week One peers on best submission practices.

The data also indicates that a factor in dropping the error and incompletion rates from Week One to Week Two was that Week Two simply had fewer of the exams where there was a likely submission preference for handwriting and uploading photos––exams that, as discussed above, were more error-prone.

Week One had 7 calculation-based exams where there was a likely submission preference for handwriting and uploading photos: AP Physics C: Mechanics, AP Physics C: Electricity and Magnetism, AP Calculus AB, AP Calculus BC, AP Physics 2: Algebra-Based, AP Chemistry, AP Physics 1: Algebra-based. Together, 814,747 students began one of these exams, 717,360 students completed the exam, 97,387 students did not complete the exam, and 4,731 distinct students experienced an error. The incompletion rate was 11.95%; the error rate was 0.58%. Week One contained the most-taken (and most-buggy) calculation-based exam: Calculus AB.

Week Two had 4 calculation-based exams where there was a likely submission preference for handwriting and uploading photos: AP Music Theory, AP Microeconomics, AP Macroeconomics, and AP Statistics. Together, 440,716 students began one of these exams, 396,088 students completed the exam, 44,628 students did not complete the exam, and 2,492 students experienced an error. The incompletion rate was 10.13%; the error rate was 0.57%.

In hindsight, the College Board perhaps should have backloaded the calculation-based math/science exams on Week Two so students could use the backup email submission option.

Exams used different form codes.

The College Board released different form codes of the same exam, leading to situations where some students may have felt they received a more or less difficult form than what their peers received. For instance, one student receiving an AP English Literature passage from the 2000s versus another student receiving a passage from the 1800s. Without multiple choice or additional FRQs to balance out the passage, students could feel they were at the mercy of the “luck of the draw.” Although a “more challenging” prompt may be frustration-inducing, readers will understand and will be evaluating student responses relative to the rubric, not relative to other students’ responses to other prompts.

Varying form codes seems to be one of the security measures that David Coleman and the AP Guide kept confidential in the lead-up to the exams. One reason for varying form codes could have been to reduce cheating rings or, at least, their size. Varying form codes could also control damage for any potential hacking. Access to an exam prompt prior to the test would provide an unfair advantage, and if there was only one prompt in existence, could obliterate the integrity and feasibility of the exam. Should a certain exam get hacked, the entire exam might not be compromised, but just a single form code.

Exception testing will occur from June 22 to June 30.

Previously, the College Board has stated that there will not be a third exam window––a makeup to the makeup exams. After the reports of glitchy submissions during the primary testing window, however, the College Board has itself made an exception by providing an exception testing window at the end of June.

Students can use an AP Makeup Request Key to request exception testing. According to the College Board, here are the acceptable reasons for exception testing:

“Students approved for makeup exams are eligible for 2020 exception testing if:

- They need to take two makeup exams that are scheduled at the same time.

- They had technical issues while testing.

- They experienced a disruption while testing.

- Illness interfered with their testing.

Other reasons for eligibility for exception testing not specified here may be recognized as valid.

Students may also request exception testing if their teacher identified an unintentional submission issue when viewing their copy of the student’s response (e.g., blank, missing, or blurry pages) from the primary testing window.”

5/18/2020: College Board Releases New Backup Submission Option by Email

Updates from Week One of the 2020 AP Exams’ Primary Testing Window (May 11 - May 15)

The 2020 AP Exams kicked off on Monday, May 11, following the timely tweet from Trevor Packer: “We’ve just cancelled the AP exam registrations of a ring of students who were developing plans to cheat, and we’re currently investigating others. It’s not worth the risk of having your name reported to college admissions offices.”

The tweet provided a clear view into the College Board’s primary concern: exam security. In good news, week one of the primary testing window passed without a successful cyber attack or crippling security blow.

The cost of exam security, however, is exam flexibility. The submission process was not as drama-free. As soon as the very first exam closed ––AP Physics–– tweets began appearing on the College Board’s twitter about submission difficulties. The reports continued to be speckled throughout the remaining exams, and developed enough of a critical mass that the College Board released more information about smoothly submitting exams.

In reaction to Week One submission issues, the College Board updated their webpage with a “Tips to Avoid Problems on Exam Day” post

The post is a point-by-point guide on addressing the most common submission problems that students had on test day, including:

- A step-by-step visual guide on how to make sure an iPhone 11 is set up for JPEGs, not HEIC. While information that HEIC photos were not acceptable was released prior to test day, it’s not hard to imagine how students focused on learning asynchronously and studying for their APs could miss it. Inevitably, there were students on test day who went in with an iPhone 11, unaware of the file format incompatibility issue.

- A side-by-side comparison of a “successful exam submission” versus an “unsuccessful exam submission.” The College Board advises that students take screenshots of their confirmation screen for their records. This new advice is likely in part a reaction to the frustrating experience students had who felt they did everything right in submitting their exams, only to be alerted that they had to sign up for a makeup exam. The logical next step was to call the College Board and request that the response be sourced from wherever it went after submission. The experience was frequent enough that Trevor Packer announced in an email to educators that there was no way for the College Board to check on whether a student’s response did actually go through.

Students can now submit responses to a unique email. but only as a backup if their initial submission fails

The College Board is doing what it can to address problems as they arise. Moving forward, a unique email address should appear if you receive an error when submitting your exam on 5/18-5/22 and also during the makeup testing window, 6/1-6/5. You must then immediately send your exam submission to that email. Unfortunately, students who’ve already tested and had submission issues cannot use this email option. Their only course of action is to request a makeup exam, as the College Board said it cannot (or will not) determine if a possibly compromised submission actually made it through.

We very much hope that this new backup option leads to fewer frustrated students and more successful submissions. If you’ve already taken AP tests and you’d be willing to tell us a bit about your experience, please do so here.

5/7/2020: Compass Webinar on 2020 AP Exams

Directors Eric Anderson and Dulcie Head hosted a presentation about the upcoming 2020 AP Exams to help alleviate any last minute concerns and provide helpful tips and tricks for test day.

Here are the three most commonly asked questions from the webinar:

How will exams be graded? Some details on point breakdowns

In prior years, the College Board released rubrics detailing the point breakdown for different steps or qualities of the FRQs. These detailed rubrics are available for some, but not all, of the 2020 Exams. For exams that do not have updated 2020 Exam rubrics, we recommend looking at prior years’ exam rubrics to see how points are parceled out. Links to those rubrics can be found in the relevant class’s AP Course page.

Overall, the College Board has leaned towards expanding the total number of possible points awarded for a free response question. The motive for doing so is likely to maximize the ability to differentiate amongst students within a shortened exam and smaller sample size of students’ abilities.

The College Board has not released how many points students would need to score a particular scale score (1-5).

Here is a compilation of scoring guideline changes to the 2020 AP Exams:

AP History Exams:

European History, US History, World History (modified DBQ rubric)

History Exams will be scored on a scale of 10 points instead of 7.

The modified DBQ rubric requires that students use fewer documents or outside pieces of evidence to score points.

Students can now earn up to 5 points, instead of 3, from “Evidence.” On a traditional AP History Exam, such as the 2019 AP US History Exam, students earn 1 point for supporting an argument with three or more documents, and 2 points for supporting an argument with six or more documents. On a 2020 AP History exam, students earn 1 point for using the content of two or more documents to address the prompt’s topic, an additional 1 point for using the content of two or more documents to support an argument, and an additional 1 point for supporting the argument using four or more documents. On a traditional AP History Exam, students earn 1 point for supplying relevant evidence beyond the documents. On a 2020 AP History exam, students can earn that same 1 point for supplying relevant evidence beyond the documents, and an additional 1 point for supplying a second piece of relevant evidence beyond the documents.

Students can now earn 2 points, instead of 1, from “Analysis and Reasoning.” On a traditional AP History Exam, students earn 1 point for analyzing how the documents support the argument. On a 2020 AP History exam, students can earn that same 1 point for one document, and an additional 1 point for analyzing how a second document supports the argument. A student can earn 2 points for two documents, instead of 1 point for three or more documents.

AP Government and Politics Exam: (modified Argument Essay rubric)

The 2020 AP Government and Politics Exam will be scored on a scale of 7 points instead of 6 points.

Students can now earn up to 4 points, instead of 3, on Evidence. On the traditional Government and Politics AP Exam, students received 1 point for providing one piece of relevant evidence, 2 points for providing one piece of relevant evidence that supports the thesis, and 3 points for providing two pieces of relevant evidence that support the thesis. On the 2020 AP Exams, students receive 1 point for providing one piece of relevant evidence, 2 points for providing two pieces of relevant evidence, 3 points for providing two pieces of relevant evidence, one of which supports the thesis, and 4 points for providing two pieces of relevant evidence, both of which support the thesis.

Students can now earn up to 2 points, instead of 1, on Reasoning. On the traditional Government and Politics AP Exam, students received 1 point for explaining how or why evidence supports their thesis. On the 2020 AP Government and Politics AP Exam, students receive 1 point for explaining how or why evidence supports their thesis, and 2 points for explaining how or why two pieces of evidence support their thesis.

Finally, students can no longer earn a point for providing an Alternative Perspective. On the traditional Government and Politics AP Exam, students received 1 point for describing and responding to an alternate perspective. On the 2020 Government and Politics AP Exam, prompts will not ask for Alternative Perspectives, and no points will be awarded for responding to alternative perspectives.

AP Language Exams:

Modified Rubrics for 2020 for Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Spanish

The 2020 Language Exams have omitted all written components, and are now exclusively speaking exams. The speaking component is divided between “Interpersonal Speaking: Conversation” and “Presentational Speaking: Cultural Presentation.” As in prior years, these speaking components are scored on scales of 0 (Unacceptable) to 6 (Excellent). The language used to qualify the “Task Completion,” “Delivery,” and “Language Use” for determining what score a response earns is identical to prior years.

AP English Exams:

No released changes to the scoring rubrics.

AP Math/Science Exams:

No released changes to the scoring rubrics.

AP Computer Science Principles:

The 2020 AP Computer Science Principles rubric is the same as the 2019 rubric (2020 Scoring Rubric)

AP Art/Music Exams:

No released changes to the scoring rubrics.

Can I wait until the makeup tests to have more time to study? Can I look at the first test and then decide to wait until the makeup test?

The answer to both these questions is technically yes, although this is discouraged. Here’s how it works.

1) Each student is given a unique credential to access the first “main” test.

2) If they don’t use it, then they’re automatically given a new unique credential to access the makeup test

3) If they do use it, but have technical difficulties, they can request a credential for the makeup test

So a student could read the first question and then shut down the exam and plead technical difficulties. There are two issues with this. First, the College Board might have some sort of monitoring to see that the internet wasn’t disrupted etc. and the request could be denied. Second, it doesn’t really get the student anything but time, and there’s no guarantee the student will “like” the makeup question better. It could even be worse.

If a student is thinking of skipping the first test date to get more study time, it would be better to not open the first test and take the automatic new credential to the makeup test. However, we do not recommend this, because if the student has real technical difficulties the second time, there is no second makeup.

Our strong recommendation is that all students should do the best they can in the standard testing window, and only use the makeup dates if they truly have to. We don’t know how glitchy this system is going to be, and we certainly can’t guarantee that the makeup dates will be glitch free, so it’s less risky to test sooner. The material may also be fresher, as it’s closer to the time of live instruction even though there’s less time to review.

As of today, there were many technical difficulties in submitting answers during the physics exam, so we highly recommend taking the test during the first, main testing window.

The makeup testing request form can be found here: AP Makeup Testing Request Form.

Only students who attempted to take an AP Exam but were unable to complete it need to use it. Students who did not take their exam during the primary testing window will automatically receive a credential to the makeup exam.

The form runs students through several questions to determine why they are requesting a makeup. If students answer “No” to a question about whether they are requesting a makeup exam due to a disturbance or technological issue, the form alerts them that their request does not qualify for a makeup.

If students answer “Yes” to the question about whether they are requesting a makeup exam due to a disturbance or technological issue, the form brings them to a menu where students must provide their AP Exam makeup key. If the request is approved, their primary testing window exam scores will be voided.

What advice do you have for submitting exams?

- Practice! Using the online demo, try out different methods of submitting until you settle on one that feels easy, quick, and comfortable. Then practice that method.

- For essay-based exams, if you are typing, use word processing software with an auto-save feature and character count. Spaces are included in the 15,000 character limit.

- For math/science-based exams, if you are hand-writing your responses, practice uploading photos or PDFs of your responses. See section 2.5.2 here.

- You may use multiple devices to submit (taking a photo of a response with your phone and then sending it to your computer), you should not log in to a single AP Exam with multiple devices. Even if this is possible, two devices may increase the risk of technological issues, and may be a red flag for cheating, even if the reasons for desiring multi-device log-in are sincere. Our advice is to rely on one single device for logging in and taking the exam. See section 2.1.5 here.

- Make your documents on which you’ll record your responses ahead of time, and be sure to add your initials, page number, and AP ID to the documents.

- Submitting is a two-step process. Students must click submit and then confirm that submission. As long as the submission is confirmed before the timer runs down to 00:00:00, the response will be considered submitted on-time, even if it takes some time to process.

- Students cannot edit text that is copied and pasted within the submission window, all edits must be made in a separate program.

- The submission box mostly keeps formatting when copying and pasting from another document. When copying from Apple Notes, the submission box does not retain paragraph indentations; when copying from Microsoft Word, it does retain paragraph indentations.

- The timer turns red when students hit five minutes remaining, but there is no sound. We recommend setting a timer to go off when there are five minutes remaining to avoid the risk of running late. Late submissions are not accepted at all.

4/29/2020: College Board Releases the AP Guide to Testing

- Security Measures

- No Grammarly plug-in! The exam won’t work if Grammarly is active.

- Students will receive e-tickets two days before each test.

- Tickets are good only for a particular student and a particular test, and are an exam security measure to prevent others from surrogate test-taking for students. For students who are not getting emails from College Board (due to a spam filter, for instance, or an incorrect email), their ticket will also be posted on My AP.

- Questions may be more difficult and speeded than questions on traditional exams.

- The AP Testing Guide states: “To give students as many different chances to demonstrate what they know as possible, a question may have more parts than can be answered in the allowed time.” Students need not answer the full question to receive 5s.

- For students receiving 1s and 2s, their teacher will be able to request a review.

- Teachers will be able to view students’ exams 48 hours after students have taken them. If scores come in unusually low, teachers can request a review. The review process addresses the concern over whether these exams will be as legitimate as those of previous years. Colleges, however, may be more concerned not with scores that are too low, but scores that are too high.

- Music Theory and World Language exams have additional tech requirements.

- Music Theory requires that students have their own recording app or software to record their performances. Students will also need to print (or hand-write) copies of the answer sheet template with staves.

- World Language requires that students use an iOS or Android tablet or smartphone. These exams (Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese, and Spanish) consist only of speaking tasks. Students must download the free AP World Languages Exam App from the Apple App Store or Google Play store. Beginning the week of May 11, students will be able to download the app and practice with it.

Details and FAQs:

Why did the College Board choose to administer the 2020 Exams in this significantly modified format?

Since announcing the at-home format of the exams in March, the College Board has opened itself up to legitimate questions and criticism from students, parents, educators, counselors, and colleges. The format of the exams created winners and losers in the inevitable disparities it invited: access to technology, fairness to students with learning differences, fairness to students testing in non-ideal time zones, reliability compared to traditional exams, unevenness in how colleges are conferring legitimacy, and so on. In a year where there were no perfect choices an analysis of the College Board’s options reveal why they chose this path for the 2020 Exams.

With students forced into remote learning in March, the College Board faced three options for the 2020 AP Exams: A) cancel; B) postpone; or C) administer the exams at-home in a modified form.

Option A), canceling the exams: accept that the exams could NOT be uncompromised in 2020, and basically choose palliative care for this year. This was perhaps the easiest way to address the 2020 Exams, and also the easiest option for the College Board to reject. Sure, there’s a certain cleanness to canceling. But imagine if the College Board had gone this route. Millions of students would not be on the short end of a broken promise. Schools would have to figure out grades, colleges would have to figure out credit, and there would be unevenness in how they would do so.

Option B), postponing the exams: maintain security, buy six months to flood the zone with supports to schools and students who need it, prioritize test integrity. Postponing might have allowed the exams to take place in the fall, if schools opened back up. Even this best-case scenario had flaws, however. Unlike the SATs, which can be administered over the course of the year, the AP Exams necessarily are optimally taken immediately after finishing the course. Postponing would invite backlash from teachers and students who would rightly decry taking challenging material months after the learning and intensive study period of their courses. Would colleges be pressured to offer credit for lower scores?

In making its decision, the College Board cites the overwhelming desire of surveyed students to have the opportunity to take the 2020 AP Exams. Of all the assessments that the College Board offers (SATs, Subject Tests, CLEP tests, etc.), the AP Program is the crown jewel. More students take AP Exams each year (nearly 3 million) than SATs (~2.2 million). The AP Program has grown steadily over the past decade, increasing by 58% from 2010 – 2018, while other programs (such as Subject Tests) have declined.

Only one option would ensure the exams actually happened at the ideal time, and so the College Board chose option C: administer the exams at-home in a modified form.

The following blog post explores the implications of that decision.

What's in the testing guide?

The AP Testing Guide contains plenty of useful advice for helping students smoothly take the exams; the degree to which students are able to execute this advice in compromised learning environments is less certain.

The 50-page review guide advises students with many sensible, easy-to-implement (theoretically, at least) tips for a smooth testing experience.

For example, the guide advises that students create the docs where they will record their responses beforehand, and labeling them clearly. APBiologyQuestion1.docx; AP BiologyQuestion2.docx.

The guide also advises students to print out formula sheets, which are required for certain math and science exams. Students sans printers can handwrite the formula sheets or download them to devices, but there is a clear advantage to a printed one: easiest to prepare, easiest to reference during a time-crunched test.

The reality is that many students are learning asynchronously from AP teachers who are also siloed. Providing the information doesn’t mean it will be acted on. The gap between best practices and actual practices will be a fissure or a gulf remains to be seen.

An AP Exam demo will be available on May 4

Exam Day Experience: https://apcoronavirusupdates.collegeboard.org/educators/taking-the-exams/exam-day-experience

Demo: https://ap2020examdemo.collegeboard.org/

This demo serves as a rehearsal opportunity for students to navigate the tech.

How are colleges reacting to the 2020 AP Exams?

The College Board is enthusiastic about colleges endorsing and giving credit for 2020 AP Exams. In an interview with Rick Hess on EdWeek, Trevor Packer noted:

“We’ve spoken with hundreds of colleges—and they’ve consistently confirmed that they will continue to use AP scores as they have in the past. The big state systems that receive the largest number of AP scores—the University of California and Cal State systems and the University of Texas systems—are among dozens of state systems that have made public statements of support, while many elite private colleges ranging from USC to Vanderbilt, from NYU to Yale, have also confirmed their support. After all, for decades colleges have always accepted AP scores from shortened AP exams taken by students in emergency conditions. The only difference is that this year, virtually all AP students are in such conditions” (EdWeek: AP Testing Continues Amid Coronavirus Crisis)

Some schools, including Northwestern, Princeton, Rutgers, and UMass Amherst are currently evaluating how they will use AP scores:

“The University is reviewing how we will evaluate AP scores for tests administered in May 2020. The change in AP test format, coverage, and administration this spring makes it necessary to reconsider the relationship between these tests and material covered and assessed in similar Princeton courses. While we continue to believe that these test scores will be helpful for placement purposes, students may be required to take an additional Princeton placement test to receive Advanced Placement credit.” – Princeton Admissions

“There is no change for how AP credits are awarded for students entering in Fall 2020. However, since some of the 2020 Advanced Placement exams will not include all of the units typically covered on those exams, students who earn scores of 4 and 5 on some exams in the 2020 test administration may need to consult with faculty and professional advisors to determine if they have the prerequisite knowledge and background to be successful in more advanced coursework in the fall semester. Once AP scores are received in July, advisors will reach out to students as appropriate with more information and guidance.” – Rutgers Admissions

Still other schools, including Columbia, Harvard, MIT, Stanford, and the University of Chicago, have not yet issued any statement about how and whether they will confer credit to the 2020 APs. We tend to read into the silence a “wait and see” policy. How seamlessly (or not) the 2020 AP Exams actually come off may drive how schools use the scores.

How effectively is the College Board bridging the digital divide?

For students without access to technology, the College Board is partnering with schools to provide access to existing technology. For students who cannot receive help from their schools, Packer noted that the College Board will be able to “provide chromebooks, tablets, and MiFi devices” –– mobile hotspots, essentially. The College Board has staffed 50 people to help address any calls for technological assistance that come by way of this form through April 24.

The extent to which these efforts are addressing the digital divide that exists amongst the population taking AP Exams remains unknown. A glimpse at Chicago Public Schools underscores the enormity of the digital divide amongst students. According to data from the 2017 school year, 77.7% of CPS students were classified as “Economically Disadvantaged Students”: students who came from families whose income was within 185% of the federal poverty line. Of the 107,352 CPS high schoolers, 22,794 CPS students took AP Exams: just over one in five high schoolers. About 17,000 of those students may qualify as Economically Disadvantaged, and at higher risk of not having optimal access to at-home, online AP Exam functionality.

In the first two weeks of April, thanks to an effort by CPS to deliver 100,000 devices to students’ homes, more students have tools to learn and take AP Exams remotely. Whether the efforts of CPS and the College Board are enough remains to be seen.

The 2020 AP Exams may be more speeded than traditional AP Exams. What are the implications for test-taking strategy and validity?

According to the College Board’s head of APs, Trevor Packer: “The online exam is designed to take the full 45 minutes to finish, so students shouldn’t panic if they don’t get all the way through” (the Elective). The structure of the 2020 AP Exams is a balancing act between exam security and student response sample size. Shortened exams increase the security by providing fewer opportunities to cheat, but they decrease the sample size of the response from students.

The College Board is confident that the validity of the exams will be uncompromised. In EdWeek, Packer noted that “Psychometricians have identified subsets of questions that have strong correlations to the questions we won’t be asking this year, so that the shorter exam will have high predictive validity, as usual with AP exams” (EdWeek: AP Testing Continues Amid Coronavirus Crisis).

While the abridged 2020 AP Exams may indeed achieve validity for the test-taking population, for individual students, the Exams’ brevity means fewer opportunities to hide suboptimal work and possibly more volatility. In a traditional year, a five-minute lapse where students might collect themselves, catch a mistake, and then restart a problem (or simply give their hand a break from incessant bubbling and writing) could potentially be absorbed without impacting the score. When five minutes are 11% of the exam time, however, the cost of even a brief detour could be steep.

Students should be prepared to hit the ground running, without a multiple choice section “warm-up.” It’s also a mistake, however, to jump into an answer without fully processing the question and not answering or obliquely answering it. As with any exam, content mastery is only part of doing well. Understanding the specific limits and format of the exam itself is crucial to shaping an optimal approach.

We suspect that FRQs tailored to the 2020 AP Exams will be available by the end of April.

Compass is currently offering an AP tutoring package special to help students prepare for the 2020 Exams. Please contact a Compass director to discuss more: (800) 685-6986.

Extended time accommodations will be applied automatically; extended breaks/extra breaks will not. How will extended time work with the two-hour spacing between exams?

As soon as students begin the exam, the online testing process will automatically adjust for extended exam time accommodations. Students with extended break / extra break accommodations, however, will not be able to use that specific accommodation. Because the exams are shortened, the College Board has determined that extra breaks are unnecessary. Extended breaks do not apply at all, as there are no breaks.

Given the exams are spaced out two hours apart, students with accommodations face uncertainty about when/how to log in for their next exam.

Students testing with 1.5x extended time will receive 67.5 minutes (no official word yet on whether the College Board will round this number up to 68 or 70 minutes). For a hypothetical student in Denver taking both Music Theory and Psychology during the primary testing window with 1.5x extended time, Tuesday, May 19, would look like this:

- 9:30 a.m.: Log in for Music Theory

- 10:00 a.m.: Music Theory Exam begins

- 11:10 a.m.: Music Theory Exam ends

- 11:15 a.m.: Submit answers

- 11:30 a.m.: Log in for Psychology

- 12:00 p.m.: Psychology Exam begins

- 1:10 p.m.: Psychology Exam ends

- 1:15 p.m.: Submit answers

At a glance, the schedule seems doable. The student will have 15 minutes between submitting answers to the previous exam and logging in for the next exam.

For a hypothetical student in Denver taking both Music Theory and Psychology during the primary testing window with 2x extended time, Tuesday, May 19, would look like this:

- 9:30 a.m.: Log in for Music Theory

- 10:00 a.m.: Music Theory Exam begins

- 11:30 a.m.: Music Theory Exam ends

- 11:35 a.m.: Submit answers

- 11:30 a.m.: Log in for Psychology

- 12:00 p.m.: Psychology Exam begins

- 1:10 p.m.: Psychology Exam ends

- 1:15 p.m.: Submit answers

The spacing between exams indicates that the student with double time would end up being five minutes late to the log-in portal for their next exam. Almost certainly, the College Board has anticipated the overlap and addressed it, though they have not yet specified any suggestions for Standard Operating Procedures during double time. The easiest place to shore up time would be in the break between exams with the log-in window. A possible solution would be that the student need only log-in once: for the first exam (Music Theory) and then could automatically transfer to the next exam (Psychology). Or, if the system is rigid and does not allow for a single log-in for multiple exams, it’s possible that the student would have to take the make-up test date.

School email addresses may block external messages, including those from the College Board.

The College Board is relying on communicating directly with students’ personal emails to update them on the 2020 AP Exams and provide information about how to take the exams. Student emails sometimes have filters, however, that will block external messages. The task of ensuring that students use their personal email addresses falls to AP Coordinators and teachers, who are working to alert parents and students to use personal emails. This is a good time for students to remember to check their spam folder.

If the June make-up exams will offer different FRQs than the May primary exams, why not a third set of FRQs for international students?

At the very least, the College Board is creating two sets of official FRQs for each exam: one for the primary testing window in May, and another for the make-up testing window in June. So why did they not create a third set of official FRQs for international students to take at a separate time? The likely answer is time and money. Exams cost significant amounts of both to develop, and the cold, hard economic fact is that there are just not enough international students who take AP Exams to justify the cost. In 2019, students in the US took 4.9 million AP Exams, while students in U.S. or non-U.S. territories that might be affected by non-ideal testing times took fewer than 150,000 AP Exams.

Instead, students who test between 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. and who are dissatisfied with their scores will be able to take a CLEP test to demonstrate proficiency.

Teachers will receive students’ completed exams within 48 hours.

The College Board has floated the idea that teachers could use the 2020 AP Exams as a final exam or other graded assignment. This relates to a different goal: soliciting teachers as AP Exam security. Trevor Packer noted, “While we are not relying on teachers to be experts at detecting plagiarism, teachers want to view their students’ responses. After all, it’s highly unlikely that a student who has written mediocre historical analyses all year long is suddenly and mysteriously perfect on test day” (EdWeek: AP Testing Continues Amid Coronavirus Crisis).

The policy opens the door to false-positives (students whose work is flagged as suspicious even when it was fairly completed) and false-negatives (students whose work is not flagged as suspicious even though it was not fairly completed). The policy is part of a compendium of security features, and will not likely be the be-all, end-all… but may be enough to generate an incident report for a student.

What rights do students have in all this? What other features will there be for students to protest any accusations of cheating? When the consequences of being called out for cheating are severe (the College Board alerting any colleges a student has applied to or will apply to with any College Board exam scores), emotions could easily run high, and students –– both innocent and guilty –– would have an interest in defending their integrity.

4/7/2020: College Board CEO David Coleman took to YouTube with Khan Academy founder Sal Khan to discuss the 2020 AP Exams in this video.

- Students must access the online testing system 30 minutes before their exam is scheduled to start to sign up.

- When an exam contains more than one free response, each question will be timed separately.

- Students cannot consult with any other individuals during the examination period.

Details and FAQs:

Students must access the online testing system 30 minutes before their exam is scheduled to start to sign up.

The motivation for such a log-in nearly as long as the exams itself is multifaceted: 1) to ensure that students are ready to start exams on time; 2) to ensure anti-cheating technology is implemented and working; 3) to provide time for any announcements.

With thousands of students logged in to the same exam, it’s unlikely that much if any of this time will be used to field questions from students.

To be safe, then, many well-intended students will likely end up at their computers long before the 30-minute log-in window. The day-of lead up to the exam could end up being as long as the exam itself.

The policy opens doors to more questions: How early can students log-in? What are the consequences for failing to log-in 30-minutes beforehand? Will there be a grace period for latecomers? What messaging will latecomers shut out of the exam receive?

When an exam contains more than one free response, each question will be timed separately.

For exams that have two FRQs, students will have 25 minutes to read and respond to Question 1, and then 5 minutes to upload their response. After uploading the response to Question 1, students will have 15 minutes to respond to Question 2, with 5 additional minutes to upload their response to Question 2. Once their response to Question 1 has been submitted, they cannot go back to it.

The College Board is keeping security measures deliberately vague.

Coleman stated that the more he talks about the security measures, the weaker they will be, an acknowledgement of the inevitabile existence of motivated entities to find a way to exploit an unfair advantage.

One security measure Coleman briefly mentioned was that students will not be able to consult with any other individuals during the examination period. Coleman did not specify the details of how to prevent students from communicating with others.

To enforce a ban on outside communication, the College Board needs an answer for every way that a student could possibly consult another individual. Online: Software to prevent any online email, chat, or video call. Via phone: an ability to monitor students so they are not using any outside communication device. In-person: a student recruiting an expert into the physical testing room for assistance may sound farfetched, but if it’s possible, it must be preventable.

Then, the College Board needs ways to make the system work remotely, en masse. Thousands of students will be taking an exam at the same time, and the logistics and expense of asking remote proctors dedicated to monitoring even a handful of students would be great. Given the exams are designed not to require proctors, live humans remotely monitoring students will not be the first and best way to detect cheating. It’s more likely that detection software will flag suspicious behaviors, and then flagged videos of students testing could be reviewed later in more detail.

For now, Coleman called for cooperation on the part of students, and how cheating is not in their best long term interest: “There’s something kind of crazy about cheating on an exam, because who wants to end up in an advanced calculus class who’s not ready for it?”

The possibility of online testing for the Fall 2020 SATs online raises the stakes for the College Board to deliver smooth, secure 2020 AP Exams.

Coleman acknowledged that the College Board will need an at-home style solution for the SATs if schools are out this fall. The AP Exams serve as a trial balloon with a smaller test-taking population. Expect another update about online SATs within a week.

4/3/2020: AP Program and COVID-19: The Essentials for School Counselors

- The primary testing dates will be May 11-22

- The make-up testing dates will be June 1-5

- Each AP Exam will be offered at the same time worldwide. Here is a link to the schedule: 2020 AP Exam Schedule.

- The make-up dates pose risks: there may be scoring delays, and if there’s a technical glitch on a make-up test, there is no make-up to the make-up.

- Students with accommodations will be able to use their accommodations.

- To read our tips for how students can apply this information to their AP Exam preparation, click here.

Details and FAQs:

The 2020 AP Exams will be offered at the same time worldwide.

All 2020 AP Exams will be offered at the same time worldwide during two weeks in May and a week in June. The College Board had previously stated that the 2020 Exams would be offered on two separate dates. Now, however, the official schedule indicates that there will be two separate date ranges, one exam, per day, per time slot, for two weeks in May (the primary testing dates) and one exam per day for one week in June (the make-up dates).

Here is a link to the schedule.

While the “everyone tests at once” model minimizes the opportunities for cheating, a cost is that there are clear winners and losers in the timeslot lottery. The College Board has not yet addressed follow-up questions about how international students will deal with testing which, per the current schedule, may end up being in the middle of the night.

Students can take a maximum of three AP Exams per day.

The 45-minute AP Exams are spaced out into two hour intervals. A student living in the Pacific Time zone taking Latin, Calculus AB, and Human Geography during the primary testing week would take three tests on Tuesday, May 12, at 9:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m., and 1:00 p.m.

Students cannot take both Japanese and Italian. CollegeBoard says this has never come up as an issue before, and they don’t expect it will be an issue this year.

Why did the College Board decide to continue with the 2020 AP Exams?

The choice was between canceling AP testing or finding a way to still support it, assuming school closures through June.

When the College Board surveyed students asking if they wanted to take their AP Exams, 88 – 94% of students said that they did. The students’ motive may partly be due to receiving AP scores for college credit can help alleviate the hefty price ticket of college-level credit hours. The main reason, however, may be that when COVID-19 forced students into remote learning situations, students had already made it through 75% of an AP course’s intensive curriculum.

The College Board also determined that it could meet the five criteria for remote testing: