SAT tutoring can be a humbling job. I learned some 20 years ago that just when I think the test makers have made a mistake, I should think again. Given the assiduous scrutiny each test item receives before it becomes operational and then scored, experienced SAT tutors who run into a perplexing solution have been wise to first ask themselves, “What am I missing?”

That all changed this month.

Here is the story of how a Compass tutor and his student discovered a test-maker error on the SAT, how we got it corrected, and what this means for all students.

May 4th, 2019

About 400,000 students awoke early Saturday morning to take the SAT, an 8am start at a College Board designated test site hopefully not too far from home. Armed with a picture ID, test registration ticket, an approved calculator, a couple of pencils, a silent timer perhaps, and maybe a light snack, each student got checked in and assigned to a room. Students would spend the next 45 anxious minutes “spelling out” their personal information, one tedious bubble at a time, before seeing even the first test question. They were in for a long day.

Once the actual exam began, students faced 65 minutes worth of dense reading passages and 52 corresponding questions. Then they took a short break. The next section, 35 minutes long, included 44 more questions that required students to carefully proofread text for errors. However one performed during those 100 fateful minutes would be converted into a scaled score from 200–800, available online a few weeks later. Yes, one-half of the SAT score that would someday soon factor into college admissions decisions was now effectively in the books, part of one’s official testing transcript.

But now was not the time to think about that; there was still a math portion to endure. Students were allowed another 25 minutes to complete the next 20 questions but also told to put their calculators away for this first math section. And as the minutes ticked by, the questions got harder; the math sections are arranged that way. Finally, after one more very short break, students embarked on the last mandatory portion of the SAT: a 55-minute, 38-question math section that allowed calculator use.

And just like the prior math section, these questions got steadily harder along the way. The two sections had something else in common, too: they switched from a multiple choice format to a free-response format for the final handful of problems (questions 16–20 in the first section; questions 31–38 in the latter). Students were to arrive at the correct answer on their own and then “grid-in” the value. And that’s where things got interesting.

Because near the end of the third hour—probably very close to noon in most cases—test takers encountered a question (the now infamous “May 2019 SAT, Math w/Calculator #35: Median” question) that would make history! Well. Or at least a good story about a tutor and a student raising about 50,000 SAT scores. I’m getting to that.

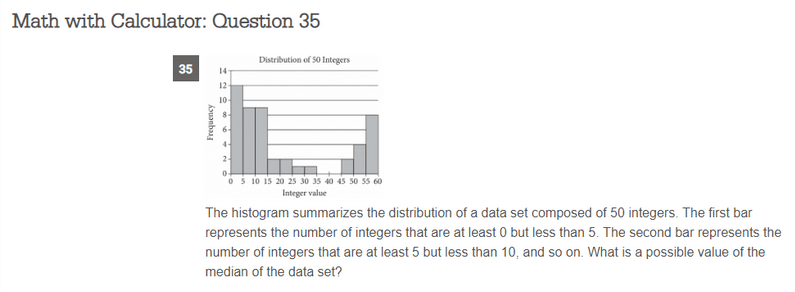

The question appears below. Try it yourself, but first try to put yourself in the shoes of an official test taker. It was not only one of the last questions of an exhausting math section; it was the 151st question of an interminably long 154-question marathon. It was not merely a somewhat difficult problem in isolation; it was also placed so that many students were mentally taxed, hungry, too hot, too cold, short on time, or all of the above when attempting to solve it.

Astute readers may have noticed a slip in something I wrote a moment ago. I did that on purpose. I said that on free-response questions students are to arrive at the correct answer on their own. But unlike multiple choice questions, free-response questions sometimes allow for a range or series of correct answers, so students must only provide *a* correct answer. Correspondingly, the test makers must then account for every possible correct answer when scoring the test. And that is where the mistake was made.

Most students understand that the median is the middle value when all of the values are sorted. The histogram means that students can’t know the exact number, but they can still find the middle. Almost. When there is an odd number of values, one of them will be in the middle. Fewer students know the rule that, with an even number of items, the two middle values must be averaged to find the median. In the question above, we want the average of the 25th and 26th list items. These should be in the third bar, since the first three have 12, 9, and 9 items. The third bar has integers greater than or equal to 10 but less than 15 (i.e., 10, 11, 12, 13, 14). These could individually be any combination of numbers inside this range. Since we’ll be averaging two, we could get any of these values and any of the half values between them. This is where the developers took a wrong turn. They assumed that the two middle values would be the same. But the 25th and 26th values did not have to be identical. That is, the 25th and 26th items could be any of the pairs 10/10, 10/11, 10/12, 10/13, 10/14, 11/11, 11/12, 11/13, 11/14, 12/12, 12/13, 12/14, 13/13, 13/14, 14/14. These result in median values of 10, 10.5, 11, 11.5, 12, 12.5, 13, 13.5, 14.

May 17th, 2019

May SAT scores, as promised, were posted online. Hundreds of thousands of test takers logged in to their College Board accounts to see their official SAT scores displayed in large numerical font on screen. Many presumably stopped there, although they could’ve double-clicked into the detailed sections of the report to see exactly how they earned a given scaled score. Because the May test is released publicly to all test takers (this is related to College Board adhering to Truth-in-Testing laws dating back to 1979 that stipulate certain transparency requirements), students were given the option to access (for an extra $18) the complete Question-and-Answer (QAS) report. The complete test—the questions and the acceptable answers—were now available to the public.

And on this report, the College Board initially recognized only integer values (10, 11, 12, 13, 14) as correct answers to the question above. An answer like, say, 12.5, was marked wrong.

May 18th, 2019

Saturdays are popular tutoring days at Compass, and this day was no different. We conducted hundreds of private sessions across the country that day, but one in San Francisco is notable because it was the one during which this mistake was first properly disputed. One of our math tutors was meeting with one of his students, and they spent some time reviewing the student’s May SAT QAS report. This is common

practice—openly encouraged by the College Board in fact—as a way to evaluate one’s own work and learn from real problems as case studies.

When they got to the above question, this whip-smart tutor (a former ACT project manager, no less) had that sinking feeling we’ve all had as tutors: “What am I missing?” I recently re-read the string of emails that ensued, and he asked that very question. After finishing the lesson, the tutor reached out to the head of our Math department in Northern California and wrote:

. . .The acceptable answers are all integers, but there are 50 items in the set, so the median would be the average of items 25 and 26, which could be 12 and 13, so I’m not sure why [my student’s] answer of 12.5 isn’t acceptable. What am I missing? It’s probably something obvious, but I can’t figure it out.

(The “test-is-never-wrong” default mindset was in full force here.)

May 20th, 2019

Our Math Lead read this on Monday morning and first thought she needed a second sip of coffee. “What the heck am I missing?” She checked her sanity with a senior member of her math training team, and he agreed she wasn’t losing her mind. The test-maker, gasp, may have messed up?

Meanwhile, I was running from my plane to an Uber in Phoenix on my way to an annual college conference when I was made aware of what was discovered. Skimming the summary on my phone, I initially surmised there must be some qualifying (or disqualifying) detail embedded in the question that limited the acceptable answers to those provided on the answer key. There was no other explanation I could accept. It seemed like the best option of my own mental multiple choice:

a) Hadn’t this question been thoroughly vetted?

b) Hadn’t this question already been used without incident on prior exams?

c) Aren’t glaring mistakes flagged before scores are sent to students and colleges?

d) We must be missing something!✔

But when I got to my hotel room that night, I looked at it again. And again. And again. And finally, I figured, I’ll ask. I sheepishly reached out to the right guy at the College Board who I knew would get to the bottom of it. I fully expected a reply that was going to embarrass me for overlooking something obvious. I heard back the next day . . .

May 21st, 2019

. . . And . . . he agreed with all of us. 12.5 sure seems like it could be correct. He would look into it with the assessment design team and get back to me.

May 23rd, 2019

I received an update that the College Board was working on resolving this mistake quickly. My contact expressed sincere appreciation for flagging this error. College Board was owning it and would presumably issue corrected scores and a statement soon.

May 30th, 2019

After a week of not hearing anything about this from anyone at College Board or elsewhere, I checked back in with my contact there. He said the resolution had just been finalized this day: an email would go out with updated scores in the next 1–2 business days. Not every student who was impacted would get an updated score because in some cases an additional raw score point doesn’t change the scaled score. In other cases, the scaled score rises by 10 points. On other test forms, one raw score point can translate to 20–30 scaled points in some instances.

(We encourage readers to post their score updates in our Comments section.)

My contact signed off by saying, “thanks again for your help here; it’s really appreciated by everyone.” He then shared a draft of the notification that would go out to affected students; it was straightforward:

Dear Student,

Your May SAT® Math score has increased slightly due to a correction on the answer key that was used to score the test. For one math question you answered correctly, the original answer key did not include all the correct answers. We have recalculated your score, and you can access it online now. If you sent your scores to a college or other organization, they will receive the updated scores early next week. Please reach out to us with any questions at 866-756-7346.

Sincerely,

The SAT Program

National Media Coverage and Broader Consequences

Soon, the media picked up on the story. Inside Higher Ed and Newsweek were among the first to cover it. (true story: A reader from the UK called Compass after seeing the Newsweek article and asked if the eagle-eyed tutor could work with her daughter. Sure!) Those articles also touched on some interesting questions. I’ll look at four big ones here:

How many students were affected on this test?

College Board hasn’t disclosed that figure so we can only make an informed guess. We think it’s greater than 8,000 (2%) and less than 80,000 (20%), probably between 25,000–50,000 students. While this particular problem doesn’t strike me as one of the hardest of the hard, the concept of histograms is foreign to some students. The location of the problem toward the very end of the section and the test suggests it was a question that has stumped most students. Perhaps as many as 75% of all test-takers, or about 300,000. I suspect the vast majority of those who got it wrong did so for other reasons: they left it blank, they guessed, or they “eyeballed” the median somewhere closer to the middle bar. If we estimate that only about 15–20% of the “wrong” answers were indeed correct, assuming only 1 in 4 got it right in the first place, that’s about 50,000 students. That may be a little high, but it could be a little low. Only the College Board knows for sure.

How many students were affected by this question on a previous test?

I don’t see how we’ll ever know. But unless and until College Board affirmatively denies that this question ever appeared as an operational item on a previous test, the reasonable assumption is that it did. Once a certain version of a test is made available to the public it will never be used again. But before that happens, it is used on test dates that do not get released to the public. Some number of SAT takers prior to May 2019 almost certainly encountered this question and received scores that did not account for this error.

Do 10 points really matter?

We’d like to think not, but in some cases it might. And, for some students this question may have been worth 20 points, depending on where they were on the scale. While college admissions officers generally realize (or at least they *should*) that the test is not designed to make meaningful distinctions between SAT scores 10 points apart, there are indeed specific instances in which exact scores matter. Earning NCAA eligibility and qualifying for certain scholarships are two examples. There are unfortunately other anecdotal cases in which college officials (admission reps, athletic recruiters) casually talk in overly precise ways about the need to reach a certain score.

Has this ever happened before?

Well, which part. Yes, mistakes happen on tests. On expensive, high stakes standardized tests constructed by professional psychometricians, they don’t happen all too often. Questions on the SAT and ACT go through rounds of development, review, and pre-testing before they become operational. And if a problematic question makes it that far, it is almost always caught in the weeks between administration and the release of scores, and then thrown out.

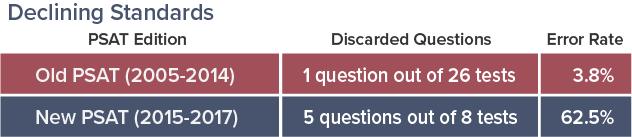

College Board used to contract with a separate entity, Educational Testing Service (ETS), to develop the SAT and manage quality control. Under ETS, very few mistakes were made. Since College Board President David Coleman took back control of the SAT, there has been a well-documented slip in quality standards. On the PSAT, for example, which is released every year, errors have appeared with more regularity.

As for a flat-out error being discovered by a member of the general public, this is a first for Compass. This experience reminded me of a similar story from 22 years ago when Colin Rizzio, a student in New Hampshire, challenged the answer to an SAT Math question and was found to be correct.

To underscore how big a deal it was at that time, Colin was covered in a New York Times article, appeared on Good Morning America, and had the offending SAT question named for him!

That story is a great read to show how things have changed since then too. Starting with the fact that Colin’s challenge went unread for many months due to the avenue he took to submit it: email.

As a College Board spokesperson explained at the time, ”We are quite used to getting inquiries from test takers at a post office mail address. This was the first time a test taker had sent a question through the Internet and it somehow just got picked up by our general customer service department.”

Now, who do we write to about getting an SAT question named for someone?