April 6 Update

It appears that the conclusion reached in our original version of this post have been confirmed. Two commenters on our primary cutoffs post have called NMSC today and been told that the Commended Student cutoff is 211 for the class of 2018. That is up 2 points from last year’s 209. This likely means that a majority of state cutoffs will rise. I am preparing an analysis of prior Commended moves to see if we can get a better sense of how likely we are to see 0, 1, 2, and 3 point changes in state cutoffs. This analysis cannot, of course, predict which individual states will rise, but it will present students with a better sense of how scores stack up. Expect an updated article no later than a week from today.

Semifinalist cutoffs will rise for the class of 2018.

The most common question about National Merit is “Will cutoffs go up or down?” Since PSAT scores were released in December, I have been trying answer that question. Based on the evidence presented below, I now believe cutoffs for the class of 2018 will be higher than they were for the class of 2017.

When I say that National Merit scores will rise this year, I am not saying that all state cutoffs will increase. There is solid evidence that the Commended Student cutoff will increase. When this level has increased in prior years, more state cutoffs have gone up than down. The higher the Commended level, the more likely that state cutoffs will move in that direction. State-by-state data is still unavailable, so I cannot predict exactly which states will increase or by how much. For an overview of where Semifinalist cutoffs were for the class of 2017 and where they might be for the class of 2018, I recommend Compass’ post on NMSF cutoffs.

Mean Scores are Higher

The first bit of information we received shortly after scores were released was that the average total score had gone from 1009 to 1019 (more exactly, from 1008.83 to 1018.51). This increase, by itself, was not conclusive. National Merit scores apply to an elite group of test-takers, and mean scores can be influenced by many parts of the score range. As I had the opportunity to dig deeper into score distributions, however, it became clear that the upper end of the score range (1400-1520 in College Board reports) was a factor in the increase. I had previously noted (in comments) the distributions as whole percentages, but I now have data that gives student breakdowns. It makes for a more compelling story.

Top Scores Show Largest Increases

As shown in the table below, the number of students scoring at 1400 or above went from 55,587 for the Class of 2017 (October 2015 PSAT juniors) to 64,875 for the Class of 2018 — an increase of 16.7%. In fact, the largest percentage increases were in the highest score ranges. Scores across the board seem to have had an upward push.

PSAT Score Range Changes - Total

| Score Range | Class of 2017 # | Class of 2017 % | Class of 2018 # | Class of 2018 % | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1400-1520 | 55,587 | 3.1% | 64,875 | 3.6% | 16.7% |

| 1200-1390 | 255,631 | 14.4% | 273,791 | 15.4% | 7.1% |

| 1000-1190 | 598,975 | 33.6% | 615,095 | 34.5% | 2.7% |

| 800-990 | 619,394 | 34.8% | 582,287 | 32.7% | -6.0% |

| 600-790 | 239,747 | 13.5% | 237,432 | 13.3% | -1.0% |

| 320-590 | 11,736 | 0.7% | 9,773 | 0.5% | -16.7% |

| Total | 1,781,070 | 0.0% | 1,783,253 | 0.0% | 0.1% |

It should be noted that not all PSAT takers are National Merit-eligible — primarily because of the requirement for U.S. citizenship. We can’t directly use the 55,587 figure, for example, to compare to the 52,000 to 53,000 students typically achieving Commended status or above. We must also be careful when using total score instead of Selection Index. The class of 2017 total score figures, though, seem to correspond well with the 209 (Selection Index) Commended cutoff. The 64-thousand student question, then, is what does the increased number of students in the upper range mean for this year’s cutoff?

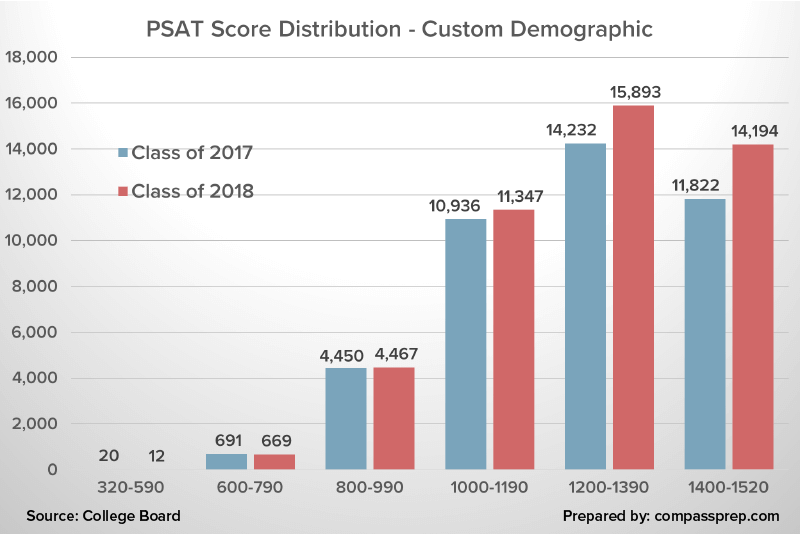

Score Increases Within Sub-Groups

An important question is whether or not the increases impacted all student segments — especially those segments that already had high numbers of top scorers. We might be able to argue that the 3.1% to 3.6% change in 1400-1520 scorers occurred because of some students being pushed just over the line from 1390 to 1400 or 1410. A sub-group with a dense population of 1400-1520 scorers, though, is also going to consist of many 1450+ students. Increases in those sub-groups provide evidence that scores increased virtually everywhere along the PSAT range.

College Board only provides a few ways of looking at PSAT data. Level of parent education is useful for our purposes because of its correlation to higher scores. For example, students whose parents have graduate degrees are almost 6 times as likely to fall into the 1400-1520 range as students whose parents do not have graduate degrees. In fact, these students represent 61% of the 1400-1520 bin. This would strongly imply that this segment has a high population of 1450+ scorers. As with the overall numbers, we see the largest percentage gain among students falling in the top bracket.

PSAT Score Range Changes - Parent Ed, Grad School

| Score Range | Class of 2017 # | Class of 2017 % | Class of 2018 # | Class of 2018 % | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1400-1520 | 34,367 | 8.9% | 39,825 | 10.2% | 15.9% |

| 1200-1390 | 105,330 | 27.2% | 112,896 | 28.8% | 7.2% |

| 1000-1190 | 147,801 | 38.2% | 148,241 | 37.8% | 0.3% |

| 800-990 | 81,601 | 21.1% | 73,516 | 18.8% | -9.9% |

| 600-790 | 17,438 | 4.5% | 16,752 | 4.3% | -3.9% |

| 320-590 | 706 | 0.2% | 590 | 0.2% | -16.4% |

| Total | 387,243 | 391,820 | 1.2% |

I also looked at a segment of students using multiple slices (confidential). This segment included only 42,151 students in the class of 2017 (about 1 student for every 42 PSAT takers) but represented 21% of 1400-1520 scorers. Not only did this group see an increased percentage of students in the top bucket for the class of 2018, it also saw almost an 11% increase in testers. Overall, this segment — one we can surmise had many 1450+ scorers — saw a 20% increase in students in the 1400-1520 range. Below I’ve provided a graphical view of the change to illustrate how the PSAT score “wave” got shifted to the right and, presumably, sloshed into even the very upper reaches (i.e Selection Indexes above 220).

Total Scores Versus Selection Indexes

One important caveat is that these figures are for total scores. College Board does not provide similar breakdowns of Selection Indexes. Because the EBRW score has twice the weight of the Math score, we cannot guarantee a perfect correlation between total score and Selection Index. Perhaps much of the increase occurred on the Math side — maybe even with EBRW scores going down. Unfortunately, this is not the case. In fact, EBRW scores seem to have increased more than Math scores. Below are the average PSAT section scores by level of parent education. Scores increased at all levels, and EBRW scores led the way. This means that it is possible that Selection Index scores saw more of an upward push than total scores.

PSAT Scores by Parent Education Level

| Parent Education Level | 2017 | 2018 | (2017) | (2018) | (2017) | (2018) | Chg | Chg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 1,781,031 | 1,782,719 | 507 | 513 | 502 | 505 | 6 | 3 |

| No Response | 115,032 | 114,096 | 425 | 438 | 434 | 440 | 13 | 6 |

| No HS Diploma | 142,682 | 151,051 | 432 | 437 | 443 | 442 | 5 | -1 |

| HS Diploma | 487,936 | 484,347 | 473 | 477 | 470 | 471 | 4 | 1 |

| Associate Degree | 132,934 | 124,621 | 495 | 500 | 486 | 490 | 5 | 4 |

| Bachelor's Degree | 515,215 | 517,495 | 536 | 542 | 528 | 531 | 6 | 3 |

| Graduate Degree | 387,232 | 391,109 | 566 | 575 | 557 | 562 | 9 | 5 |

| Custom Demographic | 42,151 | 46,582 | 602 | 616 | 640 | 640 | 14 | 0 |

National Hispanic Recognition Program

Some of the most important data points we see prior to the Commended level leaking out are scores from the National Hispanic Recognition Program. While these cutoffs are lower than those for National Merit, the multiple regions can help fit a line upward. Unfortunately, I’ve only received news about the South and Southwest regions to date (Virginia/Florida and Texas). Another problem is that NHRP switched from Selection Index to total score this year for determining cutoffs. This means that we need to make the — sometimes risky — assumption that total score and SI fall in line. The Southwest cutoff for the class of 2017 was 191; for the class of 2018 the cutoff is 1280. If we assume an even split of EBRW and Math scores, the 1280 would convert to an SI of 192 — an increase, but a very modest one. For the South, the cutoff moved from 204 to 1360. Making the even split assumption gives the exact same cutoff as last year. Finally a small bit of evidence that NMSF cutoffs may not have gone up!

The NHRP figures are intriguing because Hispanic/Latino results went up just as they did for other segments. In the class of 2017, 25,441 students scored between 1200 and 1390, and another 2,829 scored between 1400 and 1520 (NHRP recognizes about 5,000 students, but the cutoffs are regional). The figures for the class of 2018 are 27,831 and 3,363. This can be interpreted in a couple of ways. We might argue that the South is an outlier and that most regions had higher cutoffs this year. Alternatively, we could say that — despite an increase in students falling into the top ranges — cutoffs were little changed (i.e. the change was large enough to move the cutoffs). The title of this post tips my hand as to which hypothesis I find more likely.

Using Percentiles to Estimate Increases

A mistaken pathway for NMSF predictions is the use of the percentiles presented in Understanding Scores 2016 versus those presented in Understanding Scores 2015 to gauge how scores have moved. College Board lags percentile reporting by a year, so the reported figures only tell us what happened with the October 2015 test. The percentiles in the earlier version of Understanding are based on a pilot study. It’s possible, though, to get an inkling of what the additional 9,288 students in the 1400-1520 range on the October 2016 PSAT/NMSQT might mean. That’s just over 1/2 of 1% of test-takers. On the total score percentile scale, we need to move about 10 points (a bit more if we allowed for interpolation) at the relevant part of the scale. In other words, we know that 55,587 students got 1400 or above on the October 2015 test. Accounting for 64,875 students on that year’s test would require us to move down at least to 1390. Filling in the gaps with yet more assumptions, I would argue that the extra 9,288 students is evidence (not proof!) of a 1-2 point shift in the Commended level.

Why are PSAT Scores Rising?

Many have speculated about reasons why scores might go up this year. Common theories include more practice materials, improved preparation, and test familiarity based on the sophomore year PSAT. While any or all of these may have had an impact, I subscribe to one that has historical precedent — College Board doesn’t always get the scaling right. When you are talking about the top 1-3% of test-takers (depending on the state), even the smallest hiccup on a problem or two can impact scores. In theory, the scale can take problem difficulty (or the invalidation of problems as happened this year) into account. In practice, small deviations occur.

I give added weight to the “scaling theory” because the October 2015 PSAT was scaled before the final SAT scale was set in stone. College Board may have made adjustments for the October 2016 test. That would help explain why segments at all ability levels and across essentially all demographics saw score increases.

Comparing New PSAT Cutoff Changes to Old

Readers familiar with my posts on historical scores will recall my horror at what happened on the 2011 and 2012 PSATs (classes of 2013 and 2014). The Commended cutoff went from 200 to 203, and 49 of 50 states saw increased NMSF cutoffs. One might argue that this was due to some permanent shift in testing behavior except that scores settled back down again in 2013. In other words, College Board got it wrong. In half of the years from 2007 to 2014, the Commended cutoff was 201, but it was also at 200, 202 (twice), and 203 over that period. Preparation effects would have done nothing to explain those bounces.

It’s interesting — in a grad test seminar sort of way — to look at historical score distributions and Commended scores to get a sense of what level of swing in one is correlated with a given level of swing in the other.

Historical PSAT Score Range Distribution

| Subject | Range | Class of 2011 | Class of 2012 | Class of 2013 | Class of 2014 | Class of 2015 | Class of 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Reading | 75-80 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Critical Reading | 70-75 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| Critical Reading | 65-69 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 3.1 |

| Math | 75-80 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Math | 70-75 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| Math | 65-69 | 4.7 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 6.3 |

| Writing | 75-80 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| Writing | 70-75 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| Writing | 65-69 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| Commended Student | 201 | 202 | 200 | 203 | 201 | 202 |

Unfortunately, direct comparisons between old and new PSATs are difficult to make because of the significant compression in the scale at the top end (the Selection Index now tops out at 228 and the lowest class of 2017 Commended cutoff fell at 209). Scores on the old SAT were also more lopsided than they are now, with far more high Math scores than high Critical Reading or Writing scores. Additionally, the historical College Board reports do not give figures for total scores or Selection Indexes; we must look at each section in isolation. We can see, though, how certain shifts caused the biggest swings. In the “low” year for the class of 2013, Writing stands out as having an abnormally low percentage of students in the 65-80 range. In the “high” year following, Writing bounces back and 70-80 scores for Critical Reading jump a rather absurd amount (2.5% of students to 3.9%). Doing far more math with the old PSAT scores than I will present here, it does seem as if the distributions figures we are seeing this year could explain a 1-2 point SI increase.

Expectations for Cutoffs

It’s still possible that the score range movements on the October 2016 PSAT are not enough to shift cutoffs upward. The evidence, though, points to an increase. I think it’s virtually impossible that the average NMSF cutoff level will go down. The more likely result, in my opinion, is that the Commended level will move to 210 or 211. I do not think that 209 is out of the question, although I think it about as unlikely as a 3-point increase to 212. We should have an unofficial confirmation of the Commended level by the end of April. As always, I will be updating our National Merit posts or comments as we receive more information.

Related Posts

National Merit Semifinalist Cutoffs for the Class of 2018 is the hub for the most current Compass information.

PSAT National Merit FAQ provides specifics on the various points along the way from PSAT/NMSQT to National Merit Finalist or Scholar.

Historical National Merit Cutoffs provides old PSAT cutoffs unadjusted and adjusted — to the extent possible — to the new PSAT scale.

Postscript

I feel that I should address a blog post by another company that has been mentioned by several readers. The post “predicts” significant decreases in National Merit cutoffs. The post is so flawed that — if you are unaware of it — I strongly encourage you to stay that way. This footnote is for those who may already have been infected.

A Flawed Post on NMSF Cutoffs

In January, a site I’ll refer to only as PE posted their “predictions” for the class of 2018 NMSF cutoffs. They have received a good deal of attention because of the large decreases predicted. Google does many things well, but it can’t sift good information from bad when it comes to NMSF levels. I’ve received several questions about these “too good to be true” numbers. I’ve been coy about addressing the post directly because I am hesitant to shine attention on something clearly designed to garner attention rather than to add value (ah, the Catch 22 of the internet). If nothing else, this footnote provides me with an easy reference point when I am asked about the topic.

One of the points I try to make regularly is that one doesn’t need to make up predictions because the best estimates — barring clear, new inputs — are the prior year’s scores. Deviation from those knowns should be supported by evidence [as I’ve provided above and in other posts] and come with the caveat that — outside of a few insiders, perhaps — no one knows in springtime exactly where the cutoffs will fall. Much of what I and many others try to do is bring context or information. The sure sign of a useless set of predictions is one that does nothing to explain how the figures were derived.

It feels silly to seriously discuss predictions that are so obviously nonsensical, but I can’t let them go unchallenged; I consider the misinformation harmful. The lowest states are pegged at 204, which implies a Commended level there, as well. That is a 5-point decline from the class of 2017 figure. Such a large decline has never happened. Many things happen that have never happened before. But if you are going to call for a 100-year flood, you should have evidence to back it up. Is snow pack at an all-time high? Are rivers filled with silt? Why, in a year where the average PSAT score went up and when a higher percentage of students scored in the 1400+ range, would you call for a record decline in cutoffs? It’s incomprehensible, it is not going to happen, and the predictions get even sillier.

Let’s examine the fate of Alaska, Arkansas, and New Mexico cutoffs according to the PE post. All of those states had the same 213 cutoff in 2017. Arkansas’ cutoff is supposedly going to fall to 208. Alaska’s is going to fall to 211. New Mexico’s is to GO UP to 215. There is absolutely no reason to think that Arkansas and New Mexico will differ by 7 points. It’s never been true in the past and it won’t be true for the class of 2018. In another example, the post is giving false hope to students in Kansas and Minnesota when it predicts cutoffs to fall 7 points in those states. The various figures may give some indication of what has gone wrong. The PE author seems to be taking some sort of weighting of scores by combining earlier cutoffs with those of the class of 2017. He does this, however, without any regard to the fact that the test has changed! I know better than to average the cost of bread in 2017 with the unadjusted cost from 1970 to give the cost of bread in 2018.

According to PE, the top states or selection units will be MA (223), CA (222), MD (222), DC (221), VA (220), NJ (220). Could the top cutoff rise to 223? It’s possible (much more likely than the Commended level going to 204). It’s possible that Massachusetts’ cutoff will be 223. What is not possible is that not only do NJ and DC drop from the top spots, they fall behind 3 other states. That will not happen. You heard it here first.

One of the more objectionable traits of the post is including PSAT total scores as if they were comparable to Selection Indexes when discussing state cutoffs. Anyone who has read through our comments section knows how confusing and disappointing it can be when one student qualifies with a 1450 and another misses out with a 1450. Selection Index is the ONLY score used to determine National Merit. The SI is on student score reports and is easily calculated. Providing total scores without an explanation is irresponsible. [I have tried to be extremely clear in my post above as to when and why I have used total scores and how they can be misleading. NMSF or Commended cutoffs should never be stated as total scores.]

In sum, there is no truth to the predictions/guesses in the PE post except, perhaps, in a stopped clock manner.

I understand students’ and parents’ desire to have answers now rather than in August or September, but the National Merit timeline means anxious waiting for most families. I may be proved wrong in my expectation of higher scores (I’d like to be proved wrong), but I will tell parents and students how I come to conclusions and why things are often inconclusive. I trust in researchers not oracles.

Hello,

With the commended score coming out as 2 points higher, do you think that a 220 in Arizona will make the cutoff?

Dan,

You may have already seen that I published my latest thoughts on Researching NM Cutoffs soon after your question. I think 220 is likely to qualify, but there is an outside chance that the cutoff will go to 221. You are in a great position, but I’m afraid that we won’t know the “close calls” until Aug/Sept.

What about a 219 in Alabama?

Bama,

I finally had a chance to update my estimates and my research soon after your comment. A 219 should be safe in Alabama. Congratulations!

Hey Art, I live in Mississippi and I am (naturally) extremely worried about the predicted high volatility of the Mississippi cutoff score. Do you think that I should continue to plan and hope for NMS or should I move on to trying to get Presidential Scholarships for various colleges?

David,

The measure of volatility was simply a rough way of gauging how much “bounce” was seen in a state’s cutoffs. I’ve updated my estimates subsequent to your comment. I do not think MS will go higher than 215, and I think 214 is more likely. If you are in my estimated range, I would recommend remaining hopeful about a National Merit Scholarship. I think it’s wise for all students, though, to look at alternatives. Best of luck.

I probably should have included this, but I have a 212, which was what was worrying me. Do I still have a chance?

Yes, you do. Some states will see no change in cutoff.

Just wondering…what would you say about a score of 217 in SC?

Anxious,

There is a small chance that SC could hit 218. You are in excellent shape at 217!

Hi Art,

What are the chances for a 215 in Illinois?

Marianne,

Illinois has broken into the top 10 highest cutoffs in recent years, so it is extremely competitive. I don’t think it can move down more than a point from last year’s 219. You should be proud of your achievement as a Commended Student.

Do you think a 219 in Ohio is a safe bet?

Ohio,

It’s a very *good* bet, but I don’t think I can go as far as to say that it is *safe*. There will likely be a few state cutoffs this year that see increases of 3 or more points.